- Military History

- Conflicts & Wars

- World War II

- World War II History

- The Origins of World War II (WWII History Part 1)

The Origins of World War II (WWII History Part 1) The Versailles Treaty and European Diplomacy between the Wars

At 08:00 hours on August 31, 1939, a contingent of German soldiers masquerading as Poles “assaulted” a German customs facility on the Polish-German border and temporarily seized a German radio station. The “Poles” subsequently withdrew, leaving numerous corpses as evidence of the confrontation. The corpses, attired in German uniforms, were victims of concentration camps. This plan, created by SS Security Service Chief Reinhard Heydrich, provided Adolf Hitler with an ideal pretext for initiating an assault on Poland.

The assault commenced at 04:45 hours on Friday, September 1st. Two days later, Britain and France, fulfilling their commitments to Poland, declared war on Germany. The majority of Britons continue to perceive 1939 as the commencement of the Second World War. The conflict arguably did not attain the status of a true 'world' war until 1941, when Germany invaded Russia and Japan assaulted the USA. Germany's invasion of Poland was unequivocally the catalyst that ignited the global conflict.

Index of Content

The Versailles Treaty

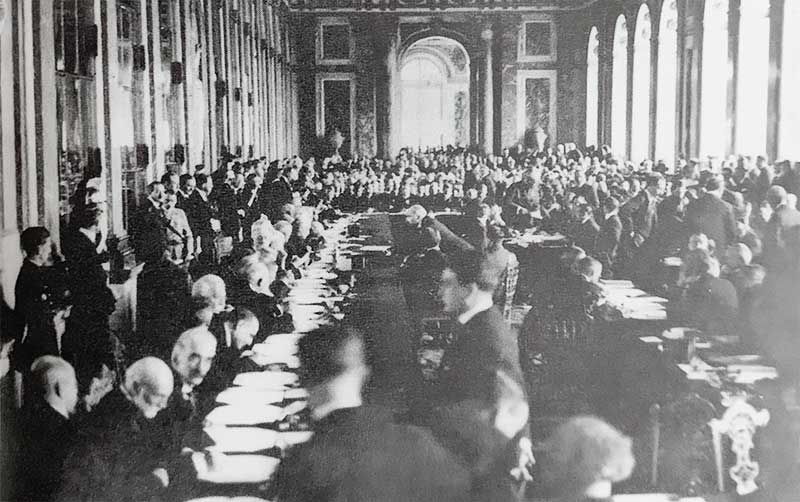

President Woodrow Wilson of the United States, Prime Minister Lloyd George of Britain, and Premier Clemenceau of France were the principal architects of the Treaty of Versailles. Each proposed a distinct solution to the primary inquiry: how to ensure future security.

Clemenceau was determined to impose a punitive peace. Germany invaded France twice during his lifetime. He sought to diminish German might to eradicate any potential future military danger. In contrast, Wilson attended the peace conference endorsing overarching concepts and aspiring to create a just framework for world relations. Specifically, he aimed to establish a League of Nations and advocated for the principle of self-determination. Lloyd George aimed to maintain Britain's naval dominance and expand the British Empire. Despite his rhetoric intended for domestic audiences, he deemed it imprudent to chastise Germany's new democratic authorities for the transgressions of the Kaiser. Mindful of the peril posed by an embittered Germany, he tended towards leniency.

According to the provisions of the Versailles Treaty, signed on June 28, 1919, Germany forfeited all of its possessions. Alsace-Lorraine was restored to France in Europe. Although the Rhineland was not separated from Germany, as Clemenceau had anticipated, it was to be occupied by Allied forces for 15 years and then remain demilitarized. Germany ceded territory to Poland in the East. Danzig was designated a Free City under the League of Nations to grant Poland maritime access, while the Polish Corridor divided East Prussia from the remainder of Germany.

Notwithstanding the concept of self-determination, Germany was prohibited from uniting with Austria. The German military was restricted to 100,000 personnel. Its military was prohibited from possessing tanks, aircraft, warships, or submarines. Article 231 of the treaty assigned culpability for initiating the war to Germany. The war guilt clause established a moral foundation for the Allied demands for Germany to compensate for “any damage inflicted on the civilian population of the Allies.” In 1921, the compensation amount was established at £6,600 million.

In contrast, the majority of the French deemed the deal excessively lenient. Following a protracted and expensive conflict, for which she bore significant responsibility, Germany persisted as the potentially most formidable state in Europe. The German population was double that of France, and its heavy industry was double in scale.

Compounding the situation, a fragmented collection of economically feeble and politically volatile governments had emerged in east-central Europe, supplanting the former Austro-Hungarian and Russian Empires. The new groups, many of which comprised significant German minorities, were improbable to become a substantial challenge should Germany regain her strength.

Versailles is sometimes characterized as the most unfavorable of all outcomes - excessively harsh for the majority of Germans yet insufficiently restrictive to limit Germany for an extended period. All Germans intended to discard some or all provisions of the treaty at the first opportunity. The primary distinction among Germans pertained to the timing and the methodologies they ought to employ.

Considering the challenges they encountered - revolutionary upheaval, economic turmoil, the disintegration of empires, and the issue of nationalism - it is remarkable that they were able to formulate a treaty at all. Despite hindsight, proposing a solution to the 'German dilemma' remains challenging. The Germans would likely have harbored resentment towards any pact, primarily because it symbolized a defeat that many were unwilling to accept. The peacemakers were cognizant of the treaty's shortcomings. This was the rationale behind the establishment of the League of Nations.

Lloyd George stated that it will serve as a Court of Appeal to rectify crudities, irregularities, and injustices. This may have been an excessive reliance on an organization that possessed neither enforcement authority nor the support of the United States. The US Senate declined to ratify the Treaty of Versailles, thereby preventing the USA from joining the League.

The Versailles Treaty and the broader Versailles settlement, which includes the Treaties of St. Germain (with Austria), Trianon (with Hungary), Neuilly (with Bulgaria), and Sevres (with the Ottoman Empire), resulted in several grievances for various nations, not solely Germany. Italy, although it was one of the victors, departed from Versailles seemingly empty-handed. Italian disillusionment facilitated Mussolini's ascent to power as Europe's inaugural fascist ruler in 1922. Fascism, often regarded as a socialist deviation, prioritized the nation before class allegiance. Mussolini failed to realize his aspirations to create a vibrant Italy. Italy did not attain first-rate power status. The primary frustrations that precipitated the crises between 1919 and 1939 were German, not Italian.

Versailles alone did not delineate the geopolitical landscape of interwar Europe. The Bolshevik Revolution (1917) and the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (1918) significantly influenced events. Finland and the Baltic States attained independence from Russia, while Poland, following a victorious conflict with Russia in 1920, successfully delineated its borders beyond those established by the Treaty of Versailles.

Following 1922, Russia, as the Soviet Union, was significantly an aggrieved force. Due to her commitment to the propagation of communist revolution, Russia persisted as an adversary to all non-communist nations.

Troubled Peace between 1919 and 1933

The principal flaw of the peace deal was not the agreements themselves, but rather the absence of consensus on their enforcement. Considering that the USA demonstrated minimal willingness to support the settlement, the responsibility mostly rested with Britain and France.

They frequently disagreed. France, apprehensive about the resurgence of a formidable Germany, continued to experience insecurity. Consequently, in addition to sustaining the most substantial military force in Europe, France pursued alliances, especially with Britain. Britain, meanwhile, was unwilling to guarantee French security through a military alliance. Britain's primary interests were the preservation of her empire and the restoration of trade. The primary issue exhausted the majority of her strength, leaving minimal resources for ensuring French security.

The second concern relied on a tranquil and thriving Europe, encompassing a tranquil and thriving Germany. The French were initially resolute in maintaining all elements of Versailles; in contrast, British sentiment quickly shifted to the belief that Germany had been unjustly handled in 1919. The 1923 occupation of the Ruhr by France, aimed at extracting reparation payments, signified the conclusion of her attempt to rigorously enforce the terms of the Versailles Treaty.

Gustav Stresemann, a pragmatic nationalist who dominated German foreign policy throughout the 1920s, claimed that collaboration with Britain and France was the most effective means to realize his objective of dismantling the Versailles Treaty. Leveraging British remorse regarding Versailles, stemming from the conviction that Germany was not exclusively culpable for the 1914 conflict, Stresemann facilitated the negotiation of a series of accords that subverted the treaty.

The Locarno Treaty (1925) curtailed reparations and reinstated Germany's status as a diplomatic equal, further solidified by its accession to the League of Nations (1926). By 1929, Britain and France had consented to terminate their occupation of the Rhineland five years earlier than planned.

In 1929, France, maintaining skepticism towards German intentions, commenced the construction of the Maginot Line defenses. Throughout the majority of the interwar period, the British relied on the League of Nations. The League emerged in the 1920s as an international entity proficient at adjudicating conflicts among lesser powers.

Nonetheless, the paramount issues of the era were resolved not by the League but by the foreign ministers of Britain, France, Italy, and Germany. Nonetheless, in 1929, there appeared to be substantial grounds for hope. Germany and France had a cordial relationship. While Mussolini's rhetoric occasionally exhibited belligerence, his actions were rather insignificant. Russia constituted an embarrassment rather than a significant issue.

The disintegration of the global economy in the early 1930s significantly influenced international relations. The Great Depression diminished the willingness of certain countries to invest in arms, but in others, it facilitated the rise of regimes that advocated for foreign invasion as a strategy to improve the economic conditions. In 1931, Japanese forces captured Manchuria from China. The League's inaction towards Japan foreshadowed future events.

The Rise of Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler ascended to power in Germany in 1933. Formed by both the Treaty of Versailles and the Great Depression, Hitler was resolute in his intent to confront the prevailing system. A substantial body of literature exists regarding Hitler, however there remains no consensus on his objectives and motivations.

Recently, numerous historians have asserted that Hitler exerted minimal influence over the Third Reich, contending that the rival agencies under his authority generated outcomes that he acquiesced to rather than directed. The Third Reich was characterized by significant administrative turmoil, rather than being an effective dictatorship. Nonetheless, the trajectory of German foreign policy unequivocally mirrored Hitler's aspirations. While his approach exhibited some opportunism, it also encompassed several distinct objectives.

These objectives encompassed the dismantling of Versailles, the establishment of a Greater Germany, and the acquisition of living space (lebensraum) in the East. Convinced of the imperative of military conflict, he was prepared to jeopardize peace to realize his objectives. Although numerous “ordinary” German statesmen would have been pleased to achieve his accomplishments by 1939, few would have employed his tactics or undertaken the risks he embraced.

In light of Germany's military frailty, Hitler's initial foreign policy actions were measured. In October 1933, asserting that other nations would not regard Germany as an equal, Hitler exited the League. Initial aspirations for camaraderie with Britain and Italy failed to materialize. Efforts to secure a formal accord with Britain were unsuccessful, and Hitler's state visit to Italy in 1934 proved to be a calamity.

The events in Austria during July 1934 exacerbated tensions between Hitler and Mussolini. A Nazi-inspired coup resulted in the demise of Austrian Chancellor Dollfuss. Mussolini perceived Austria as an Italian satellite and swiftly deployed troops to the Austrian border. Hitler accomplished nothing, and the Nazi coup was unsuccessful.

Hitler's initial significant risk occurred in March 1935 when he openly rejected the disarmament provisions of the Versailles Treaty. This constituted a blatant challenge to Germany's previous adversaries. In April, Britain, France, and Italy denounced Hitler's actions and committed to opposing any efforts to alter the existing treaty agreements through coercion.

The Stresa Front rapidly disintegrated (the Stresa Front was a short-lived 1935 alliance between Britain, France, and Italy designed to curb German rearmament and uphold the Treaty of Versailles. Formed in April 1935 in Stresa, Italy, it aimed to protect Austrian independence and maintain European stability). In June, Britain established a naval accord with Germany, permitting Germany to construct up to 35 percent of Britain's capital ships and granting parity in submarines. Britain appeared to be acquiescing to German rearmament notwithstanding the Stresa Front's denunciation.

By the mid-1930s, France had established a succession of alliances with minor powers in Eastern Europe from the 1920s, a defense treaty with Russia in 1935, and held the belief that Britain should not be estranged. The French dependence on British benevolence allowed Britain to have a dominant role in shaping the response to Hitler. For centuries, a primary strategic aim of Britain has been to thwart any single country from attaining hegemony on the Continent. This was the fundamental reason Britain declared war on Germany in 1914. The death of 750,000 Britons in the war incited universal abhorrence of war as a means of policy.

Britain and France anticipated that Mussolini may serve as a valuable ally against Hitler. Nonetheless, Mussolini harbored personal ambitions, particularly to expand the Italian Empire. In October 1935, Italian troops invaded Abyssinia (Ethiopia). When Emperor Haile Selassie of Abyssinia petitioned the League of Nations, Britain and France faced a difficult situation. Taking action against Italy may compel Mussolini to align with Hitler. However, significant principles were involved - particularly regarding the Western countries' commitment to uphold their responsibilities under the League's covenant.

The British government, swayed by public sentiment, denounced the invasion and endorsed League intervention. France acted similarly. The outcome - economic sanctions imposed on Italy - yielded minimal impact. Italian troops invaded Abyssinia. If Britain and France had taken a stand against Italy, it might have deterred Hitler. The Abyssinian crisis dealt a fatal blow to the League, which once more failed to prevent an aggressor. Mussolini aligned himself more closely with Hitler, who had endorsed his acts.

In March 1936, Hitler contravened the Versailles Treaty by deploying troops into the demilitarized Rhineland. He recognized he was undertaking a risk: Germany remained insufficiently robust to engage in a protracted conflict. His assessment of the situation - that Britain and France would not contest his actions - was indeed correct. France merely transferred the issue to Britain by inquiring whether it would endorse French intervention. British sentiment regarded Hitler's actions as lamentable in execution, although not perilous in essence.

The majority of Members of Parliament (MPs) concurred with Lord Lothian's assertion that Germany possessed the legitimate right to enter its own “backyard.” Germany commenced the construction of fortifications in the Rhineland, so complicating any future actions by France. In hindsight, the Rhineland was perhaps the final opportunity to halt Hitler without engaging in a significant conflict.

The Spanish Civil War commenced in July 1936. Germany reaped the most advantages. The conflict provided Hitler with an opportunity to test new weaponry and also resulted in enhanced relations with Italy. In October 1936, Mussolini announced the Rome-Berlin Axis, asserting that the two nations would control Europe, with all other states orbiting this “axis.” During the Second World War, the word “Axis” referred to all the powers allied with Germany.

In November, Germany and Japan executed the Anti-Comintern Pact, an accord aimed at curbing the proliferation of communism, with Italy joining in 1937. The alliance proved ineffective, mostly due to the lack of coordination among the signatories. Nonetheless, the Pact appeared formidable. Germany was rearming; Italy posed a threat in the Mediterranean; and Japan was formidable in the Far East. Britain had few options except to initiate comprehensive rearmament.

An influential perspective persists that the Second World War constituted a conflict against fascism. The Anti-Comintern Pact indicates an ideological aspect to the struggle. Italian fascism and German Nazism shared numerous similarities: the veneration of a charismatic leader, a focus on action, intense nationalism, paramilitary elements, and the conflation of the state with the party and its leader. However, there were also distinctions.

The Nazis had a significantly greater obsession with race compared to the Italian fascists, as seen by Mussolini's relationship with a Jewish lover. Imperial Japan did not embody fascism. Despite many similarities, such as a repudiation of democracy, fervent nationalism, and veneration of the military, Japan lacked a charismatic leader and was not a single-party state. The nation formed an alliance with the fascist powers, albeit in a manner. The Axis was fundamentally a coalition of powers characterized by authoritarianism, militarism, nationalism, and anti-communism, rather than fascism.

World War II in Sight (1937)

Neville Chamberlain assumed the office of British Prime Minister in May 1937. His frail demeanor concealed his self-assurance and determination. The term indissolubly associated with Chamberlain is "appeasement," referring to policies of acquiescing to menacing demands to avert conflict. Appeasement has typically received negative criticism. Proponents of the initiative, particularly Chamberlain, are frequently regarded as “guilty men” whose erroneous policies contributed to the onset of war. Critics of Chamberlain maintain that appeasement merely intensified Hitler's ambitions and prompted him to issue further demands.

Nonetheless, appeasement may be perceived in a more favorable light. For centuries, a fundamental tenet of British policy has been that resolving problems via negotiation and compromise is preferable to warfare. Appeasement should not be exclusively linked to Chamberlain; the willingness to acquiesce to German demands for modifications to the Versailles Treaty had become entrenched British policy by the mid-1920s. France was also dedicated to appeasement. Haunted by the casualties of the First World War and beset by political and social divisions, France had apprehensions over conflict with Germany.

For France, appeasement was fundamentally detrimental - a strategy imposed upon her by frailty. For Britain, there existed a more favorable aspect. Although the Nazi administration was largely unpopular in Britain, the perspective that Germany possessed legitimate grievances, especially regarding the status of Germans beyond its borders, garnered significant support. As Hitler commenced rearmament and posed a threat, the inclination to bargain rather than confront became increasingly urgent. The perception that Hitler may possess valid grievances, along with apprehensions over a potential violent conflict in Europe and the extensive devastation of British cities by the swiftly growing Luftwaffe, contributed to the belief that appeasement was the most prudent strategy to adopt.

Chamberlain, sympathetic to Hitler's aspiration to unify the German-speaking populations of Austria, Poland, and Czechoslovakia, anticipated achieving this through peaceful means. He acknowledged that until Britain possessed sufficient equipment, "we must endure with patience and good humor activities we would prefer to address differently." He possessed minimal confidence in France or the USA, and even less in Russia. Nonetheless, he maintained an optimistic outlook. In 1937, he asserted, “I believe the dual strategy of rearmament and improved ties with Germany and Italy will guide us securely through this perilous moment.” Winston Churchill, the leading opponent of appeasement, subsequently earned a reputation for being right about Hitler, unlike Chamberlain, who was considered wrong.

In actuality, Chamberlain likely possessed a more astute understanding of the circumstances - particularly Britain's deficiency in power - than Churchill.

In July 1937, Sino-Japanese animosity intensified into a comprehensive conflict. Japanese armies occupied a significant portion of China. In the late 1930s, Britain primarily focused its efforts on Europe instead of the Far East. Nonetheless, apprehension of Japanese aggression significantly influenced Britain's eagerness to appease Italy and Germany.

In November 1937, during a conference with some of his principal commanders, Hitler delineated his objectives. He claimed that his objective was to acquire Lebensraum (“living space or room” - It was used by the Nazis to suggest that Germans needed more land or area for German-speaking peoples), attainable just through warfare. The primary objective was the annexation of Czechoslovakia and Austria.

The importance of this gathering, known as the Hossbach Conference, has been a subject of dispute. Some believe it demonstrates that Hitler had a schedule for aggression. Some believe that he was merely indulging in daydreaming. Indeed, events did not transpire as he had foreseen. But the winter of 1937–1938 marked the beginning of a new era in German politics. Faithful Nazis replaced numerous prominent conservatives in significant roles. Ribbentrop, for instance, assumed the role of Foreign Minister.

Notwithstanding its prohibition by the Treaty of Versailles, Hitler remained resolute in his ambition to unify Austria and Germany. A multitude of pro-Nazi Austrians espoused analogous perspectives. Since 1934, the Austrian government, unable to depend on Italian assistance, has endeavored to manage its Nazi factions. In early 1938, Austrian authorities uncovered schematics for a Nazi insurrection, the suppression of which would serve as justification for a German incursion.

In February 1938, Austrian Chancellor Schuschnigg resolved to meet with Hitler, aiming to convince him to curtail the Austrian Nazis. This constituted an error. Intimidated and coerced, the Austrian leader acquiesced to Hitler's requests to include Nazis in his cabinet. At this juncture, Hitler intended to do little more. Ironically, Schuschnigg once more instigated events by declaring in early March his intention to conduct a plebiscite about Austria's potential unification with Germany.

Hitler, apprehensive that the vote could be unfavorable, insisted on the annulment of the referendum and threatened warfare. Schuschnigg abdicated. Austrian Nazis assumed control and requested Hitler to deploy soldiers to Austria to maintain order. Hitler returned victoriously to his motherland and proclaimed Austria's complete integration into the Third Reich.

The unification, or Anschluss, received overwhelming approval in a plebiscite conducted by the Nazis. Britain and France received minimal forewarning of the Austrian issue, which is unsurprising given that Hitler made his decision to intervene at the last moment. Chamberlain, acknowledging his limited options, took no action. France issued a protest.

Czechoslovakia (1938)

The Anschluss promptly drew attention to Czechoslovakia, now encircled by German territory. Merely fifty percent of the nation's 15 million inhabitants were Czechs. It also included Slovaks, Hungarians, Ruthenians, Poles, and around three million Germans residing in the Sudetenland. In 1938, the Sudeten German Party was advocating for either autonomy or annexation by Germany.

It garnered backing from Germany, where the Nazi press vehemently criticized the Czechs (with some justification) for oppressing Sudeten Germans. Hitler despised the democratic Czechoslovak state. The presence of formidable military forces indicated a potential threat. In March 1938, he directed Sudeten leaders to request de facto independence. Benes, the Czech president, resolved to resist German pressure, assured of receiving assistance from Britain and France. Many Western politicians expressed sympathy for Czechoslovakia, with a select few, such as Churchill, deeming it worthy of military intervention.

Chamberlain was excluded from that group. He was amenable to the cession of the Sudetenland to Germany, contingent on its execution in a peaceful manner. Britain had no treaty commitment to defend Czechoslovakia and was incapable of providing military assistance. Chamberlain's primary worry was not Czechoslovakia, but rather France. If Germany were to assault Czechoslovakia, France would likely intervene on her behalf. Britain may then be compelled to assist France. French leader Édouard Daladier was reluctant to engage in war. His strategic perspective mirrored Chamberlain's: Czechoslovakia was indefensible. He would be pleased if Britain provided him a pretext to evade France's 1935 commitments.

In May 1938, on erroneous reports of German military movements, the Czechs organized their reserves and readied for conflict. Britain and France cautioned Hitler against invading Czechoslovakia. Hitler was incensed. The Western nations achieved a diplomatic triumph as he appeared to retreat from an invasion that he was not actually contemplating. He therefore commanded his military officers to ready themselves for an assault on Czechoslovakia in September.

As summer progressed, tension escalated. By September, public sentiment in Britain and France was polarized. Some believed that the Western nations ought to back the Czechs, while others contended that war must be avoided at all costs. Hitler maintained the pressure. In September, Hitler insisted on self-determination for the Sudeten Germans and threatened warfare.

Beneš announced the imposition of martial law in the Sudetenland. Numerous Sudeten Germans sought refuge in Germany, where they recounted experiences of severe oppression. A conflict between Czech and German forces was imminent.

To preserve peace, Chamberlain traveled to meet Hitler on September 15th. He acquiesced to Hitler's principal demand for the cession of the Sudetenland to Germany. In exchange, Hitler consented to postpone the invasion of Czechoslovakia to provide Chamberlain the opportunity to confer with the French and the Czechs. Hitler, anticipating that the Czechs would decline to relinquish the Sudetenland and that Britain would subsequently abandon them, was elated.

Chamberlain's government and the French promptly acquiesced to Hitler's demands. Benes had no alternative but to act similarly. On September 22nd, Chamberlain returned to Germany to confer with Hitler at Godesberg. To Chamberlain's dismay, Hitler declared that the prior plans were inadequate. The Czech concessions did not align with his desires. Polish and Hungarian assertions regarding Czech territory also needed to be addressed. Furthermore, to safeguard Germans from Czech aggression, Hitler insisted on the quick occupation of the Sudetenland.

Although Chamberlain advocated for the acceptance of Hitler's new ideas, numerous members of his government opposed them. Daladier subsequently announced that France would fulfill its obligations to Czechoslovakia. Britain and France commenced preparations for warfare. On September 27th, Chamberlain addressed the British populace, stating, “How dreadful, astonishing, and unbelievable it is that we should be excavating trenches and testing gas masks here due to a dispute in a distant nation involving individuals of whom we are entirely unaware ... I would readily do a third visit to Germany, should I believe it would be beneficial.” The following day, Chamberlain was presented with his opportunity. Hitler, cognizant of the general German disinterest in war, acquiesced to Mussolini's proposal for a Four Power Conference to negotiate a resolution for the Sudetenland issue.

On September 29th, Chamberlain, Daladier, Hitler, and Mussolini convened in Munich. The accord established closely resembled Hitler's Godesberg demands. Benes was compelled to relinquish the Sudetenland. Chamberlain convinced Hitler to endorse a joint declaration in which both individuals committed to exerting their utmost efforts to maintain peace. Munich is frequently regarded as a significant failure for the Western nations.

They arguably ought to have acted honorably and engaged in warfare to save a comrade. Nonetheless, Chamberlain perceived Munich as a triumph. Despite his disadvantaged position, he accomplished the majority of his objectives. War was averted, Germany's valid objections were resolved, and Czechoslovakia retained its sovereignty. In 1938, the majority of British and French individuals perceived Munich as a success.

Chamberlain and Daladier were regarded as heroes upon their return home. Chamberlain proclaimed to jubilant crowds that he had achieved “peace with honor.” Churchill, who characterized British strategy as a “complete and unmitigated disaster,” was part of a minority. The potential consequences of a conflict over Czechoslovakia have captivated historians ever since. A multitude have embraced Churchill's perspective that it would have been more advantageous for Britain and France to confront Germany in 1938 rather than in 1939.

Germany significantly benefited from extensive rearmament in 1938–1939 and the disintegration of Czech authority. Furthermore, Russia, constrained by treaty obligations, may have indeed aided the Czechs. Neither Britain nor France was prepared for war. French forces stationed along the Maginot Line would have been mostly ineffective in assisting Czechoslovakia. It is also uncertain whether Russia would have intervened to assist the Czechs.

Chamberlain was unconvinced that Munich enhanced the security of peace, and he was increasingly resolute that the momentum of rearmament must not diminish. Munich provided him with a reprieve. In early 1939, he received several erroneous intelligence reports forecasting German actions against Poland, Holland, Czechoslovakia, or Switzerland. In February, his cabinet concurred that a German assault on Holland or Switzerland would result in a British declaration of war.

In a significant policy shift, Chamberlain pledged Britain to the establishment of a substantial army capable of engaging in combat on the Continent if necessary. French sentiment also shifted towards opposing Nazi expansion. Numerous French citizens believed that if Germany annexed additional land in the East, it could ultimately become excessively powerful in the West.

Subsequent to Munich, Czechoslovakia encountered significant internal challenges. The majority of Slovaks harbored minimal affection for the Czech-dominated state and wanted independence. By March 1939, the circumstances were so dire, both domestically and internationally, that the newly appointed President Hacha declared martial law. This futile endeavor to maintain Czechoslovakia accelerated her demise.

Hitler directed Slovak officials to solicit protection from Germany and to proclaim independence. As his nation disintegrated, Hacha requested a meeting with Hitler, anticipating potential assistance. On March 15th, Hitler informed Hacha that German forces planned to invade Czechoslovakia imminently, presenting him with the sole options of war or a peaceful occupation. Hacha capitulated to the threats and consented to German occupation, claiming it would avert civil conflict. A German protectorate was created over Bohemia and Moravia, while Slovakia attained nominal independence.

Hitler asserted that he acted lawfully, only adhering to the demands of the Czechs and Slovaks. Nonetheless, he had evidently butchered a diminutive neighbor. Nor could he assert that he was consolidating Germans into a singular German state. Chamberlain was incensed. Hitler unequivocally indicated his intent to pursue objectives beyond merely rectifying the injustices of Versailles.

Poland and the Beginning of World War II

In mid-March, Hitler compelled Lithuania to return Memel, which Germany had lost in 1919. Once more, Britain and France failed to take action. It seemed unimaginable to consider waging war over Memel, a German city to which Hitler might justifiably assert a claim. Poland, which was ostensibly Hitler's next target, presented a different situation. Approximately 800,000 Germans resided in Poland. The majority resided in Danzig and the Polish Corridor. No German government, particularly under Hitler, was inclined to regard the Danzig situation or the partition of East Prussia as a permanent arrangement.

Poland was as resolute in maintaining the status quo. German-Polish ties have been notably amicable since the ratification of a non-aggression treaty in 1934. Germany has frequently suggested to Poland that they could turn this accord into an alliance against Russia. However, Poland, eager to avoid becoming a German satellite, rejected these proposals.

In January 1939, Hitler conferred with Beck, the Polish Foreign Minister, and demanded Danzig along with a German-administered road or rail connection through the Polish Corridor. The Poles declined. The German demands intensified. By late March, rumors suggested that a German offensive against Poland was approaching.

On March 31st, Britain made the unprecedented decision to guarantee assistance to Poland in the event of an unprovoked assault. France provided a comparable assurance. The guarantees have faced significant condemnation. Western powers may have favored Poland the least among all Eastern European nations.

Until 1939, Poland had limited allies, with the exception of Germany. Hitler's demands of Poland were more rational than those imposed on Czechoslovakia in 1938. The promises may be regarded as “blank checks” issued to a nation infamous for its imprudent diplomacy.

Furthermore, ultimately, the “checks” were valueless, as there was minimal assistance that Britain or France could provide to Poland. Nonetheless, Britain and France believed it was imperative to take action. The pledges served as a caution: should Hitler persist in his expansionist ambitions, he would encounter warfare. The pledges did not constitute a complete commitment to Poland.

The future of Danzig was considered negotiable, and Chamberlain anticipated that a combination of diplomacy and strength could persuade Hitler to engage in negotiations. More incensed than dissuaded, Hitler commanded his military leaders to be ready for conflict with Poland by the conclusion of August.

Determined to surpass Hitler, Mussolini embarked on his own "adventure." In April 1939, Italian troops invaded Albania. Mussolini declared that the Italian sphere of influence should now include the Balkans. Mussolini's belligerent rhetoric and conduct appeared to constitute an additional menace to the stability of Eastern Europe. Britain and France have now provided guarantees to both Greece and Romania under the identical conditions as those extended to Poland.

In May, Mussolini and Hitler executed the Pact of Steel, an agreement mandating mutual assistance in the event of conflict. As summer progressed, the situation in Poland worsened. The Germans alleged that Poland initiated a campaign of terror against Polish Germans.

In the case of a German assault, only Russia could provide Poland with prompt military assistance. Consequently, the most rational course of action for Britain and France appeared to be forming an alliance with Russia. In the late 1930s, France and Russia had not undertaken significant measures to reinforce their 1935 defense treaty. During the 1930s, Britain resisted any alliance with Russia, thinking that the true objective of Soviet strategy was to entangle Britain and France in a conflict with Germany.

Chamberlain believed there were numerous valid reasons to refrain from forming an alliance with Stalin, who was perceived as more malevolent and antagonistic in his long-term intentions than Hitler. British intelligence suggested that Soviet forces, following Stalin's purges, possessed minimal military efficacy. Under pressure from the media and Parliament, Chamberlain consented to initiate negotiations with Russia.

His primary objective appears to have been to leverage the prospect of a Soviet alliance as an additional admonition to Hitler. Stalin's ideology continues to be a subject of speculation. Superficially, his stance appeared grave. Hitler was an avowed adversary of Bolshevism, while Japan posed a menace in the East. Nevertheless, the assurances from Britain and France to Poland provided him with considerable latitude for action. He might advocate for advantageous conditions from the Western powers and simultaneously pursue an agreement with Germany.

The Anglo-French-Soviet negotiations were intricate and protracted. The negotiations ultimately reached an impasse when the Russians inquired if Poland would permit the deployment of Russian troops prior to a German assault. The Poles, profoundly wary of Russian motives, remained steadfast on this matter.

Chamberlain expressed sympathy for Poland. He failed to see the necessity or desirability of Russian troops stationed in Poland. Stalin asserted that this disposition led him to believe that Britain and France were not sincere in their negotiations. It is probable that the Russians issued a series of requests that they were aware Britain and France would reject, as Stalin had no desire for an alliance with the West.

Beginning in 1933, Russia intermittently initiated overtures to Germany, advocating for enhanced relations. Hitler had rejected each of these. The concept of a Nazi-Soviet pact was entirely nonsensical from an ideological perspective. During the spring and summer of 1939, Russian and German diplomats diligently endeavored to achieve an agreement. As Germany's imminent assault on Poland approached, Ribbentrop traveled to Moscow and, on August 23rd, executed the Nazi-Soviet non-aggression Pact. The clandestine provisions of the Pact partitioned Poland and Eastern Europe into zones of German and Russian dominance.

Hitler was ecstatic. He realized that Poland could no longer withstand defense, and he was confident that Britain and France would reach the same conclusion. The path was consequently clear for the German assault on Poland, scheduled to commence on the 26th of August. Chamberlain has faced significant criticism for his inability to establish a Russian partnership. He had minimal passion for it. However, such an alliance was likely unattainable for any Western leader. The sole proposition the West presented to Stalin was the possibility of conflict. In contrast, Hitler proposed peace and land concessions. From Stalin's perspective, the Pact appeared to safeguard Soviet interests, at least in the immediate term.

Hitler was willing to take risks, however he neither anticipated nor desired a war on two fronts. He believed the Western leaders would evade their commitments to Poland. Alarmed by their resolve to support Poland and unsettled by Mussolini's declaration of Italy's neutrality, Hitler deferred his attack. Desperate last-minute diplomatic efforts proved ineffective. On September 1st, German forces invaded Poland.

Chamberlain, aiming to align with French leaders eager to finalize their mobilization strategies prior to declaring war, refrained from promptly issuing an ultimatum to Germany. To some British MPs, it appeared that he was attempting to circumvent his obligations. On 2 September, the British House of Commons unequivocally asserted that a declaration of war was imperative. Consequently, at 09:00 hours on the 3rd of September, Britain issued an ultimatum to Germany. Germany did not respond, and at 11:00 hours, Britain declared war. France complied at 17:00 hours.

Conclusion to the Origins of World War II

We can broadly regard the conflict that began in 1939 as the latter part of a thirty-year war. Britain, France, and Russia waged the First World War to restrain Germany. A similar rationale dictated the declaration of war by Britain and France in 1939. Both nations apprehended German hegemony over Europe. Nevertheless, the thirty-year war thesis alone is insufficient to elucidate the onset of conflict. In 1939, Britain and France harbored apprehensions against Germany due to their concerns regarding Hitler.

The period from 1919 to 1939 was marked by a succession of crises related to the terms of the Versailles settlement. It appears peculiar to attribute the onset of the Second World War on the Treaty of Versailles, given that much of the settlement had been disregarded without conflict. Ironically, Germany engaged in warfare for her final and most justifiable grievance - Danzig and the Polish Corridor.

The prevalence of conflicting political beliefs throughout the interwar years does not, in isolation, elucidate the origins of the war. The trajectory toward conflict entailed evolving affiliations among diverse ideological allies. Moreover, both national interests and ideological considerations dictated the nations' foreign policies. It is difficult to ascertain if national interests or ideologies were predominant, as Hitler's worldview prioritized national interests.

The responses of Britain and France to Hitler's dismantling of the Versailles Treaty significantly contributed to the onset of war. In retrospect, both nations ought to have engaged in military intervention prior to 1939. Chamberlain is frequently considered the primary culpable individual. In fairness to Chamberlain, the sole alternative to collaboration with Hitler was warfare.

Decisive action in 1938 would have instigated, rather than averted, war. Chamberlain may be criticized for both appeasement and his failure to maintain it. Britain possessed neither a moral obligation nor an apparent interest in defending Poland. Chamberlain should have permitted - even advocated for - Hitler's eastward expansion towards Russia.

Hitler's aspirations and deeds were predominantly accountable for the commencement of war. Consequently, his actions precipitated a series of crises across Europe, generating an almost inescapable impetus for war. His assault on Poland was entirely deliberate.

He anticipated that the Western nations would refrain from conflict, although he was ready to accept that risk. Chamberlain and Daladier believed they had few alternatives besides engaging in combat. In 1939, British and French sentiment predominantly favored war, despite the recognition and even exaggeration of its horrors, particularly regarding bombing. For Britain and France, the concern was as much Hitler as it was Poland. This was an untrustworthy individual; therefore, he had to be restrained.

Important Dates

1918

End of the First World War

1919

Versailles peace settlement: German grievances

1933

Hitler came to power in Germany. He was determined to overthrow the Versailles settlement

1935

Germany began to rearm

1936

German troops occupied the Rhineland

1938

- The Anschluss: Germany united with Austria

- Munich Conference: Hitler won the Sudetenland from Czechoslovakia

March 1939

British and French guarantees to Poland

August 1939

Nazi-Soviet Pact

September 1939

Germany invaded Poland: Britain and France declared war on Germany

Read the next part:

- {{#owner}}

- {{#url}} {{#avatarSrc}}

{{name}} {{/url}} {{^url}} {{#avatar}} {{& avatar}} {{/avatar}} {{name}} {{/url}} - {{/owner}} {{#created}}

- {{created}} {{/created}}