- Military History

- Conflicts & Wars

- World War I

- History & Theaters WWI

- World War I - Historical Background (1871–1914)

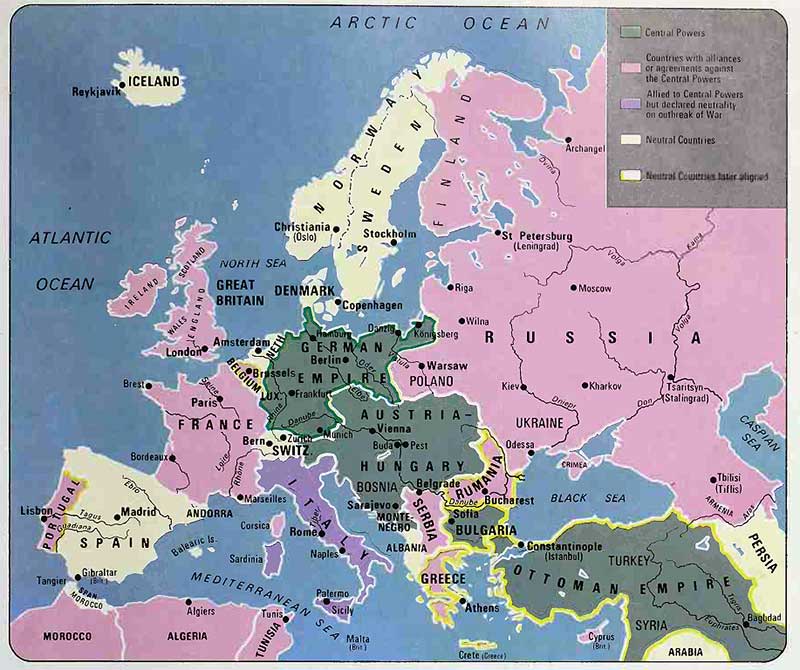

World War I - Historical Background (1871–1914) Hostile alliances dominating Europe

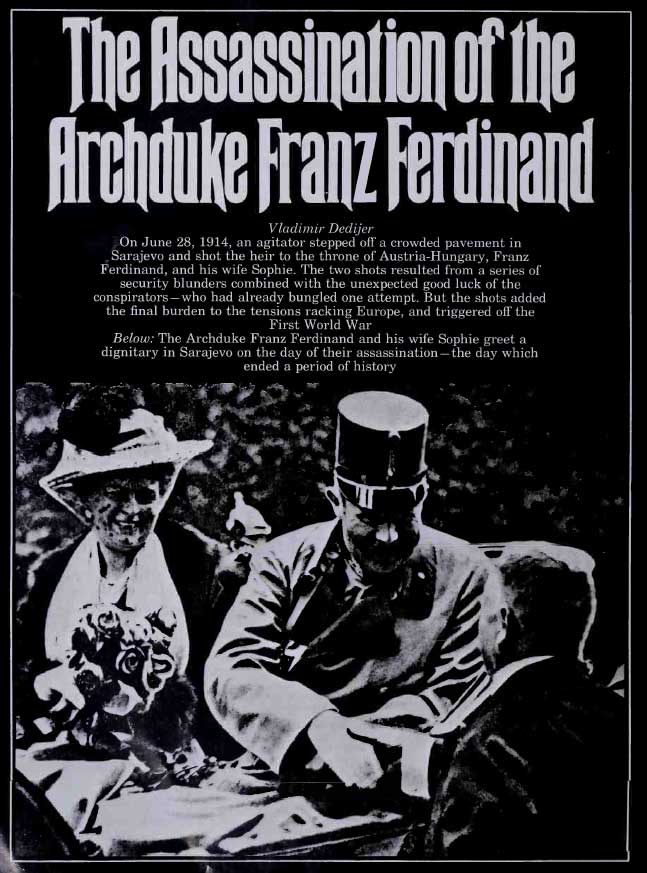

Featured World War I was triggered by the assassination of Austria-Hungary’s Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife, Archduchess Sophie, in Sarajevo, Bosnia-Herzegovina, on June 28, 1914. Europe had been a boiling cauldron for a long time, but this event detonated a devastating chain of events.

Index of content

- Background and Causes of World War I

- World War I - Resources and War Plans

- World War I – The Trigger

- World War I – The Nations Mobilize

- Principal Combatants of World War I

- Principal Theaters of World War I

- Declarations during World War I

- Major Issues and Objectives or World War I

- Outcome of World War I

- Approximate Maximum Number of Men under Arms

- Approximate Number of Casualties

- Treaties of World War I

Background and Causes of World War I

Two hostile alliances dominated Europe at the beginning of the 20th century: the Triple Alliance of Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy; and the Triple Entente of France, Russia, and Great Britain. Lesser agreements supplemented these broad alliances, which bound the major signatories to render military aid to several small nations. The conditions were thus ripe for the immediate escalation of relatively minor conflicts into a conflagration that would engulf all of Europe.

The grand alliances of the early 20th century had their origin in the statesmanship of Otto von Bismarck (1815–98), the Prussian chancellor who reshaped Europe in 1871 by creating a unified Germany following Prussia’s victory against France in the Franco-Prussian War. Because of the war, Germany gained the coal-rich Alsace- Lorraine region, creating, Bismarck understood, lasting enmity between France and Germany. Bismarck moved to isolate France from potential allies by tying both Russia and Austria-Hungary to Germany.

In 1873, he negotiated the Three Emperors’ League, binding the three powers to assist one another in time of war. In 1878, Russia withdrew, and Germany and Austria-Hungary signed the Dual Alliance in 1879. The agreement bound the signatories to aid one another if either were attacked by Russia. In 1881, Bismarck negotiated the Triple Alliance. In 1883, Austria-Hungary and Romania concluded an alliance, to which Germany agreed to adhere. Then, in 1887, Bismarck negotiated a secret “Reinsurance Treaty” between Germany and Russia, by which the two nations agreed to remain neutral if either became involved in a war with a third power unless Germany attacked France, or Russia attacked Austria-Hungary. With this secret treaty, Bismarck hoped to keep Germany from facing a two-front war against France and Russia, but the alliance lapsed in 1890.

When Russia left the German sphere, it formed an alliance with France, culminating in the Franco-Russian Military Convention of 1894, intended specifically to counter the Triple Alliance. Next, France concluded a secret agreement with Italy, which despite its obligations under the Triple Alliance agreed to remain neutral if Germany attacked France or if France, to protect its “national honor,” attacked Germany. By the beginning of the 20th century, Britain also altered its policy of “splendid isolation” in 1902 by concluding with Japan a military alliance intended to check German colonial advances in the Pacific and Asia. Two years later, Britain signed the Entente Cordiale with France, which opened the way for close cooperation between the two nations in diplomatic and military matters. In 1907, the Anglo-Russian Entente was signed.

The Triple Entente was not an outright military alliance, but in 1912 Britain and France concluded the Anglo-French Naval Convention, whereby Britain pledged to protect the French coast from German naval attack, and France promised to defend the Suez Canal. The signatories also agreed to consult if either were attacked on land. The Franco-Prussian War had created a permanent enmity between Germany and France, yet Western Europe was deceptively peaceful until the outbreak of war in 1914. In the Balkans, however, war was chronic.

In 1911–12, Italy and Turkey went to war over Turkey’s African possessions. The result was that Turkey lost Libya, Rhodes, and the Dodecanese Islands to Italy. No sooner had Turkey concluded peace with Italy than it found itself at war with Greece, Serbia, and Bulgaria, which, joined later by Montenegro, fought Turkey over possession of territories on the Balkan Peninsula. The war was ended by intervention from the “great powers” of Western Europe, who forced Turkey to relinquish Crete and all of its European possessions.

A Second Balkan War erupted in 1913 when the “Young Turks” (Turkish army officers who aimed to overthrow the ancient and corrupt rule of the sultans) denounced the peace after Bulgaria attacked its recent allies to gain more of Macedonia, which had been ceded by Turkey because of the first war. The Balkan allies quickly beat back Bulgarian forces in a series of bloody battles between May and July 1913. During July and August, Romania declared war on Bulgaria, invaded the country, and took its capital, Sofia. The Turks also prevailed against the Bulgars, reoccupying Adrianople, which had been lost in the first war. Bulgaria surrendered on August 10, 1913.

The Balkan Wars not only failed to resolve the tensions that had been mounting in this part of Europe but also fanned the flames of nationalism among the small countries that had been torn between Turkey and Austria-Hungary for so long. Individual countries sought independence, yet they also sought a “pan-Slavic” identity, a solidarity with one another and with Russia, which readily presented itself as the spiritual, cultural, political, and military defender of all Slavic peoples.

Thus the Balkans emerged as the cauldron in which war, fueled by Europe’s great opposing alliances, would brew.

World War I - Resources and War Plans

By the time war broke out in 1914, the major combatants had invested years in planning for the conflict. In 1914, the French army numbered 4.5 million men, most of them conscripts, and Germany mustered 5.7 million, also mostly draftees. At sea, France had 14 modern dreadnought battleships and 15 of the earlier pre-dreadnought types. In addition, the French navy had 76 submarines and a variety of other surface vessels. The German navy had 13 dreadnoughts and 30 older battleships, as well as 30 submarines, and many other surface craft. Unlike France and Germany, England had no program of compulsory military service.

In 1914, its British Expeditionary Force (BEF) was a superbly trained body of professional volunteer soldiers, but it numbered only 160,000. Contrary to that, the reserve forces were a poorly trained and poorly equipped Territorial Army, intended only for defense of the home territory. The Royal Navy was more formidable. England had 24 modern dreadnought-type battleships, and it also had 38 pre-dreadnoughts. Besides 76 submarines, the Royal Navy fleet included a mighty array of other surface vessels.

The Allies took much comfort in the muster rolls of the Russian army, which in 1914 showed 5.3 million men. With a population of 77 million, compared to 41 million for Germany, Russia had a vast pool of manpower from which to conscript an even bigger force. The problem was that the Russian army, though vast, was poorly trained, led, and equipped. Nor was the nation’s navy impressive.

Germany could take little comfort in the Austro-Hungarian Army of 1914. True, it was large (2.3 million men) but it was poorly organized, and many of its troops felt far more allegiance to their Slavic brothers than to the Dual Monarchy. The Austro-Hungarian Navy was comparatively small.

Strength of numbers was not the only measure of military power in 1914. The technology of war had advanced since the Franco-Prussian War. Besides the mighty dreadnought battleships (huge, heavily armored platforms for high-powered naval artillery), technological innovations included the machine gun, more powerful and accurate artillery, and advanced rail networks. The machine gun multiplied the effectiveness of small parties of defenders. New artillery, combined with improved high-explosive shells, made combat deadlier than ever. Railroads would be used extensively for the rapid transport of huge numbers of troops. Later in the war, the development of the tank and the increasingly effective use of the airplane would also make their mark on battle.

Beginning in the late 19th century, the belligerents had been drawing up grand strategies for using their large armies and the new weapons of war. After the debacle of the Franco-Prussian War, French military planners concentrated on war strategies intending to recover the lost territories of Alsace-Lorraine. Plan XVII, the French primary plan in effect in 1914, was almost entirely offensive and called for an immediate and overwhelming concentration of force against the Alsace and Lorraine region.

Little thought was given to fighting a defensive war, which, in fact, the war on the western front proved to be. Plan XVII called for four major forces to advance into Alsace-Lorraine on either side of the Metz-Thionville fortresses, which had been occupied by the Germans since 1871. Originally, the plan foolishly ignored the possibility of a German advance through neutral Belgium, but a last-minute alteration deployed troops to check such an advance. French commanders believed that an overpowering patriotism amounting to an irresistible life force animated the French soldier. A charge into German territory, French generals believed, would send the invaders running back to their homeland.

Not only was the blind faith tragic but also Plan XVII had been planned based on a gross underestimation of German troop strength and a confidence that the Germans would mobilize only first-line troops and not reserves.

Like the French, the Germans had a master war plan. It had been planned at the beginning of the 20th century by Count Alfred von Schlieffen (1833–1913). Like the French Plan XVII, the Schlieffen Plan relied on taking the offensive, but in contrast to the French plan, it also included a strong defensive component. Also, whereas Plan XVII had been painted in broad strokes, the Schlieffen Plan was meticulously detailed and geared to a precise timetable.

Schlieffen understood that Germany would have to fight on two fronts, against the French to the west and the Russians to the east. He reasoned that the French, with a more modern army, were the greater of the two threats, because they could mobilize quickly. In contrast, the Russians, though many, were poorly equipped and poorly led. It would take them at least six weeks to mobilize effectively. Therefore, Schlieffen developed an offensive plan against France and a defensive plan against Russia.

The aim was to invade France with overwhelming force and at lightning speed, while simultaneously holding off a Russian invasion of eastern Prussia. France was to be neutralized within a matter of weeks, after which forces could be transferred from the western front to the eastern in order to transform the defensive war against Russia into an invasion.

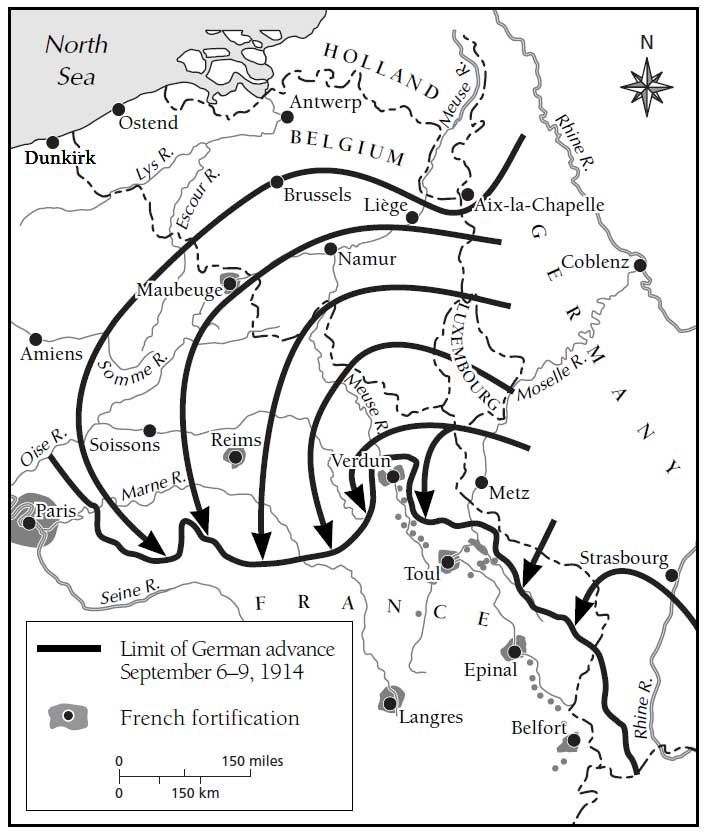

Whereas the French plan called for a direct frontal assault on Alsace and Lorraine, Schlieffen called for a “great wheel,” a wide turning movement across Flanders Plain, northeast of French territory, then into France from the north. Five principal German armies would cut a vast swath through France and Belgium, from Alsace- Lorraine all the way west to the English Channel in order to outflank the French forces, hitting them where they were most vulnerable, mainly from the rear. Best of all, the “great wheel” would immediately carry the war into France, where the fighting would wear down French infrastructure and menace French civilians.

Should tactical retreats be necessary, German troops could retreat farther into French territory rather than fall back into Germany. Brilliant as the Schlieffen Plan was, it called for executing extremely complex movements with machinelike precision over great distances and in adherence to a strict timetable. It would take little to derail the plan.

Both Austria-Hungary and Russia also had their military plans. Austria-Hungary’s Plan B shortsightedly assumed that the war would be confined to Serbia, calling for three Austrian armies to invade Serbia and another three to watch the border with Russia. When the war rapidly expanded beyond Serbia, Plan R was activated, calling for more of Austria-Hungary’s forces to be concentrated against Russia, in the south, in coordination with German action in the north. Yet it never really got under way, because the demands of the Schlieffen Plan prevented the Germans from committing sufficient forces against Russia at the outset of the war. Austria-Hungary was doomed to spend most of the war desperately and ineffectively thrashing against Italy and Russia, with significant loss of life on all sides.

The Russians adhered to a variety of plans. Plan G assumed Germany would commit most of its troops against Russia, not France (precisely the opposite of what Germany actually did). Plan G called for little more than exploiting the vastness of Russia, a resource that had defeated no less a conqueror than Napoleon (1769–1821) in 1812. The Germans could invade until the Russian armies could mass sufficient combat power to launch a massive counteroffensive and drive the invaders out.

Russia’s French allies were aghast at the wholly defensive tenor of Plan G and persuaded the Russians to develop Plan A, which assumed that the Germans would throw the bulk of their forces against France rather than Russia. Here, the Russians were to advance simultaneously into East Prussia and Galicia (southeast Poland and the western Ukraine). From here, the Russians would advance into Silesia (southwestern Poland and northern Czechoslovakia), ultimately concentrating in southern Poland. What neither French nor Russian planners appreciated, however, is that the massive but poorly equipped and miserably led Russian army could not shift rapidly from Plan G to Plan A.

World War I – The Trigger

From the perspective of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Serbia was a troublesome country. Its independence stood as a provocative example to other Balkan territories, which were provinces of the Dual Monarchy. Worse, certain forces within Serbia, most notably the Black Hand, a secret society consisting mostly of Serbian army officers, actively worked to foment rebellion among such Balkan states as Bosnia-Herzegovina. Clearly, Serbia wanted Bosnia- Herzegovina to be part of a grand Slavic state, but Bosnia- Herzegovina was now a province of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

The heir apparent to the Hapsburg throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand (1863–1914), decided that an official visit to the provincial capital, Sarajevo, would assert Austria-Hungary’s dominance over Bosnia-Herzegovina and take Serbia down a peg. To ensure that the message of dominance came across, the archduke’s visit in 1914 was scheduled for June 28, St. Vitus’s Day, a great Serbian national holiday known as Vidovan.

The visit to Sarajevo was well publicized, and even the route of the archduke’s motorcade was made public. The Black Hand recruited a small cadre of assassins, all fanatical students, and deployed them along the route. Only one of these assassins, Gavrilo Princip (1894–1918), succeeded in his mission, firing at Franz Ferdinand from almost pointblank range. Both the archduke and his wife, Archduchess Sophie, were killed almost instantly.

There was no evidence of official Serbian complicity in the assassination. Count Leopold von Berchtold (1863–1942), Austria-Hungary’s foreign minister, seized on the incident as an excuse for punishing Serbia and quashing Bosnian nationalism and the pan-Slavic movement that threatened to erode the Dual Monarchy. Berchtold, in fact, wanted to provoke a local war against Serbia, but in the Europe that Bismarck had engineered, a local war was all but impossible.

Kaiser Wilhelm II (1859–1941) assured the Austro-Hungarian ambassador, Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg (1856–1921), on July 5, 1914, that Germany would back Austria-Hungary even if it meant war with Russia. Armed with this assurance, Austria-Hungary delivered a set of ultimata to Serbia, which included a demand that Austrian officials be given full authority to operate within Serbia to root out sources of anti-Austrian agitation and propaganda.

After securing an assurance of Russia’s military aid, Serbian officials actually agreed to almost all of Austria-Hungary’s demands, stopping short of entirely relinquishing its sovereignty. Serbia would not grant authority for Austrian officials to operate in Serbia. The rejection of this single item was deemed a cause for war. On July 29, 1914, Austrian river gunboats shelled Belgrade, capital of Serbia. World War I had begun.

World War I – The Nations Mobilize

Austria-Hungary and Serbia had officially mobilized on July 28. Russia had begun a partial mobilization on that day and a general mobilization on the 30th. Germany issued an ultimatum to Russia, demanding that it cease general mobilization. To France, Germany issued another ultimatum, threatening it with war if it mobilized at all. Russia rejected the German ultimatum; its mobilization would continue. France stated nothing more than that it would consult its “own interests.” Germany took this as a negative reply as well. On August 1, 1914, Germany ordered general mobilization and began execution of the Schlieffen Plan.

On August 2, Germany demanded free passage through Belgium. By the time King Albert (1875–1934) of that nation refused the demand, German divisions were already marching through Flanders. The Great War was now under way on the western front. On August 3, the British government announced its pledge to defend Belgium. That evening, Germany declared war on France. On the 4th, having already invaded it, Germany declared war on Belgium, and Britain declared war against Germany.

On August 5, Austria-Hungary responded to the Russian mobilization along its border by declaring war against Russia. Serbia declared war against Germany on August 6. Montenegro, another of the Balkan countries, declared war against Austria-Hungary on August 7 and against Germany on August 12. France and Great Britain declared war against Austria-Hungary on August 10 and on August 12, respectively. Japan joined in against Germany on August 23, and Austria-Hungary responded with a declaration against Japan on August 25, then against Belgium on August 28. On February 26, 1914, Romania had renewed with the Central Powers a secret anti-Russian alliance it had originally concluded with Germany in 1883. However, it remained neutral, as did Italy.

Principal Combatants of World War I

Austria-Hungary, Germany, Romania, Bulgaria, and Turkey (the Central Powers) vs. Serbia, Russia, Belgium, France, Great Britain, Italy, Japan, the United States (the Allies)

Principal Theaters of World War I

Western and Eastern Europe, the Balkans, colonial Africa, colonial Asia, colonial possessions in the Pacific (with associated naval action), naval action chiefly in the Atlantic.

Declarations during World War I

- Austria-Hungary against Serbia, July 29, 1914

- Germany against France, August 3, 1914

- Germany against Belgium, August 4, 1914

- England against Germany, August 4, 1914

- Austria-Hungary against Russia, August 5, 1914

- Serbia against Germany, August 6, 1914

- Montenegro against Austria-Hungary, August 7, 1914

- Montenegro against Germany, August 12, 1914

- France against Austria-Hungary, August 10, 1914

- Great Britain against Austria-Hungary, August 12, 1914

- Japan against Germany, August 23, 1914

- Austria-Hungary against Japan, August 25, 1914

- Austria-Hungary against Belgium, August 28, 1914

- Italy against Germany and Austria-Hungary, April 26, 1915

- United States against Germany and Austria-Hungary, April 6, 1917

Major Issues and Objectives or World War I

World War I was triggered by the assassination of Austria-Hungary’s Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife, Archduchess Sophie, in Sarajevo, Bosnia-Herzegovina, on June 28, 1914, but the chief underlying issues included:

- Germany wanted to become more influential among its European neighbors and to amass a colonial empire.

- The Austro-Hungarian Empire sought to stamp out nationalist rebellion among its Balkan provinces.

- France wanted to recover Alsace-Lorraine, the eastern provinces it had lost to Prussia (now Germany) because of the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71).

- Russia, seething with revolution and the threat of revolution, wanted to restore the prestige it had lost in the Russo-Japanese War (1904–05) by gaining territory at the expense of its rival Turkey, and presenting itself to the world and to its own discontented citizens as the spiritual, cultural, and military champion of all Slavic peoples everywhere.

- Great Britain wanted to check the colonial ambitions of Germany, seen as a rival to empire.

- Italy wanted territorial

- Turkey wanted to recover lost territory and diminished imperial prestige.

- The United States entered the war ostensibly in defense of its rights as a sovereign neutral nation, after Germany attacked U.S. shipping and made other threats against U.S. neutrality.

- All of the nations involved were bound by a constraining set of treaties and alliances, some of them secret.

Outcome of World War I

The Allies (without Russia, which made a separate peace with Germany early in 1918) prevailed against the Central Powers, compelling the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the virtual disarmament of Germany, and levying ruinous reparations against Germany.

Approximate Maximum Number of Men under Arms during World War I

65,038,810

Approximate Number of Casualties during World War I

- 8,020,780 (military)

- 6,642,633 (civilian)

- 21,228,813 military wounded

Treaties of World War I

- Treaty of London, May 30, 1913, among the Balkan League (Greece, Bulgaria, Serbia, and Montenegro) and the Ottoman Empire (Turkey), ending the First Balkan War

- Treaty of Bucharest, August 10, 1913, among Romania, Greece, Serbia, and Montenegro on one side and Bulgaria, ending the Second Balkan War

- Treaty of Constantinople, September 29, 1913, between the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria, constituting a separate peace between the Ottoman Turks and Bulgaria following the Second Balkan War

- Secret Treaty Between Germany and the Ottoman Empire, August 2, 1914

- Treaty of London, April 26, 1915, alliance among France, Russia, Great Britain, and Italy

- Sykes-Picot (Secret) Agreement, May 9, 1916, among Britain, France, and Imperial Russia, defining the goals of the Allied powers of Britain, France, and Russia for the partition of the Ottoman Empire at the victorious close of the Great War

- Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, March 3, 1918, separate peace concluded among Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, and Turkey with Russian Federal Soviet Republic after the Bolshevik Revolution

- Treaty of Versailles, June 28, 1919, among United States (signed, but failed to ratify), British Empire, France, Italy, and Japan (“Principal Allied and Associated Powers”), Belgium, Bolivia, Brazil, China, Cuba, Ecuador, Greece, Guatemala, Haiti, the Hedjaz, Honduras, Liberia, Nicaragua, Panama, Peru, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Serb-Croat-Slovene State, Siam, Czechoslovakia, and Uruguay (“The Allied and Associated Powers”) and Germany, constituting the principal document ending World War I

- Covenant of the League of Nations, June 28, 1919, among United States (signed, but failed to ratify), British Empire, France, Italy, and Japan (“Principal Allied and Associated Powers”), Belgium, Bolivia, Brazil, China, Cuba, Ecuador, Greece, Guatemala, Haiti, the Hedjaz, Honduras, Liberia, Nicaragua, Panama, Peru, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Serb- Croat-Slovene State, Siam, Czechoslovakia, and Uruguay (“The Allied and Associated Powers”) and Germany

- Treaty of Guarantee, June 28, 1919, postwar alliance between Great Britain and France

- Treaty between the Allied and Associated Powers and Poland on the Protection of Minorities, June 28, 1919, among the “Principal Allied Powers” (United States [signed, but failed to ratify], British Empire, France, Italy, and Japan) and “Associated Powers” (Belgium, Bolivia, Brazil, China, Cuba, Ecuador, Greece, Guatemala, Haiti, the Hedjaz, Honduras, Liberia, Nicaragua, Panama, Peru, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Serb-Croat-Slovene State, Siam, Czechoslovakia, and Uruguay) and Poland

- Treaty of Germain, September 10, 1919, among “Principal Allied Powers” (United States [signed, but failed to ratify], British Empire, France, Italy, and Japan), and “Associated Powers” (Belgium, China, Cuba, Ecuador, Greece, Nicaragua, Panama, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Serb-Croat-Slovene State, Siam, and Czechoslovakia) and Austria, dissolving the Austro-Hungarian Empire

- Treaty of Neuilly, November 27, 1919, among the “Principal Allied Powers” (United States [signed, but failed to ratify], British Empire, France, Italy, and Japan) and the “Associated Powers” (Belgium, China, Cuba, Greece, the Hedjaz, Poland, Portugal, Romania, the Serb-Croat-Slovene State, Siam, and Czechoslovakia) and Bulgaria, by which Bulgaria ceded territory to Serbia (the Serb-Croat-Slovene State) and Greece

- Treaty of Trianon, June 4, 1920, among The “Principal Allied Powers” (United States [signed, but failed to ratify], British Empire, France, Italy, and Japan) and the “Associated Powers” (Belgium, China, Cuba, Greece, Nicaragua, Panama, Poland, Portugal, Romania, the Serb-Croat-Slovene State, Siam, and Czechoslovakia) and Hungary, reducing the area of Hungary

- Treaty of Sèvres, August 10, 1920, among the “Principal Allied Powers” (United States [signed, but failed to ratify], British Empire [UK], France, Italy, and Japan) and the “Associated Powers” (Armenia, Belgium, Greece, the Hedjaz, Poland, Portugal, Romania, the Serb-Croat-Slovene State, and Czechoslovakia) and Turkey (Ottoman Empire), by which the Ottoman Empire was formally dissolved

- United States and Austria Treaty of Peace, August 24, 1921

- United States and Germany Treaty of Peace, August 25, 1921

- United States and Hungary Treaty of Peace, August 29, 1921

- {{#owner}}

- {{#url}} {{#avatarSrc}}

{{name}} {{/url}} {{^url}} {{#avatar}} {{& avatar}} {{/avatar}} {{name}} {{/url}} - {{/owner}} {{#created}}

- {{created}} {{/created}}