- Military History

- Conflicts & Wars

- World War II

- World War II History

- The Blitzkrieg (WWII History Part 2)

The Blitzkrieg (WWII History Part 2) The conquest of Poland, France, and the Disaster at Dunkirk

From Rommel's point of view, things did go “all fine.” Four days later, thanks to his daring leadership, his division pushed past the French positions on the River Meuse. In the days that followed, his tanks - and a host of tanks from other panzer divisions - surged into northern France, heading for the English Channel. By June 1940, France had surrendered, and German victory in the European war seemed imminent.

Index of Content

The Conquest of Poland, 1939

German triumph in 1939-40 was not as clear as it later appeared. Few things in Nazi Germany were as magnificent as Nazi propaganda portrayed. This was true for the armed forces. In 1939, the German command system lacked a central headquarters responsible for strategy or service coordination. In effect, Hitler's unique will drove strategy. The three service heads, General Brauchitsch (Army), Hermann Göring (Luftwaffe), and Admiral Raeder (Navy), zealously defended their respective powers. Brauchitsch gave Hitler competent military advise.

Göring, one of the Third Reich's most successful political barons, retained the outlook of a former fighter pilot and lacked the broad perspectives required for command. Raeder had a few new ideas.

The German army (Wehrmacht) has planned an attack on Poland since March 1939. With the majority of their forces deployed in the east, Wehrmacht officials were aware that Germany's western border was vulnerable to French attack. Consequently, German soldiers had to win soon. The aim was to launch a series of major offensives through Polish defenses, encircling and destroying the main German forces. The German high command had not yet fully developed the notion of blitzkrieg (lightning war). Direct military support, for example, was not among the Luftwaffe's top priorities. The Germans formed 54 divisions.

There were six tank (or panzer) divisions. There were four motorized infantry divisions. The majority of the rest were standard infantry divisions that marched to fight on foot. Army Group North had 630,000 personnel, while Army Group South had 886,000.

The odds against Poland's survival were small. The Polish army, which numbered over a million people, lacked adequate equipment. Poland lacked the industrial capacity to develop substantial quantities of sophisticated weapons. The Poles had 180 tanks (compared to the Wehrmacht's 2,000) and 313 combat aircraft (against the Luftwaffe's 2,085). Geographical issues undermined Poland's position. Poland had no natural borders and was bounded by Germany on three sides.

Polish officials deployed their forces thinly throughout the border regions from the Carpathians to the Baltic, hoping to safeguard their country's economically critical western territories. There was no meat underneath the thin crust. To complicate matters, Poland did not begin mobilization until August 29. Britain and France advocated against Polish mobilization, fearing that it would provide Hitler with a reason for aggression. As a result, when the war began, only one-third of Poland's army was prepared and ready to fight.

German forces struck on September 1, 1939. The Polish air force was quickly wiped from the skies. Luftwaffe strikes on the railway system hampered Polish mobilization. Polish forces battled valiantly, but cavalry with lances were no match for German tanks. Panzer divisions made deep advances into Poland, separating the Polish army into "pockets". Ordinary infantry divisions cleaned up. By September 10, German forces controlled the majority of northern and western Poland. To make matters worse for the Poles, on September 17, Russia attacked from the east, as planned in a secret protocol to the Nazi-Soviet Pact. Britain and France did not go to war with Russia. The British reasoned that the Anglo-Polish alliance only covered the German attack.

The Soviet intervention just hastened what was already inevitable. By September 17, German soldiers had encircled Warsaw. The heavily battered city surrendered ten days later. By October 5, Polish resistance had come to an end. Polish casualties were 70,000 dead, 133,000 wounded, and 700,000 held prisoner. The Wehrmacht lost approximately 14,000 lives. General Sikorski established a Polish government-in-exile in France, as well as an army-in-exile consisting of 84,000 men. However, Poland had effectively vanished. Germany annexed Danzig and the territory between East Prussia and Silesia. She also established a new division, the General Government. Russia took over Eastern Poland.

From a Polish perspective, there was little to choose between German and Russian barbarism. Both German and Russian soldiers set about removing Poland's governing classes. The most horrifying incident was Russia's slaughter of 15,000 surrendered Polish officers at Katyn in 1940.

Britain and France did little while German soldiers crushed Poland. A Franco-Polish contract signed in May 1939 guaranteed the Poles that France would launch a full-scale attack on Germany within 15 days of the start of the war. This promise was not fulfilled. Although France enjoyed a three-to-one advantage on the Western Front in September, there was no plan to mount a massive offensive. French officials felt themselves safe behind the Maginot Line. They had a complementary regard for Germany's (far from full) defenses, known as the Siegfried Line.

The tiny British troops could do nothing. In any case, Premier Neville Chamberlain had no desire for an instant shooting conflict. He believed that time was on the Allied side: stronger Allied economic resources, combined with a naval blockade, would be sufficient to drive Germany to its knees. Unfortunately, the Nazi-Soviet Pact guaranteed Hitler's access to Soviet raw materials. He might also utilize Italy and a number of other neutral countries to avoid the Allied blockade. However, the German economy surely suffered. Between September 1939 and April 1940, the value of German imports plummeted by around 75%. German gasoline stocks plummeted by one-third, complicating military preparations.

On October 6, Hitler made peace proposals to Britain and France. He stated he had no rights against France and desired friendship with Britain. All the two countries needed to do was accept the new order in Eastern Europe. Hitler appears to have sincerely sought peace with Britain and France so that he could concentrate on Russia. Few Allied leaders, however, were willing to trust him. Furthermore, they did not go to war solely for Poland; they wanted to maintain the European balance of power. Peace with Hitler would be shame and defeat.

Édouard Daladier, the French premier, established the Government of National Defense. In Britain, Chamberlain named Winston Churchill First Lord of the Admiralty. Several ministries from the previous war were restored, including shipping, information, and food. Ships traveled in convoys. News was restricted. Rationing was introduced.

Unfortunately, Allied commanders were unable to agree on a unified command structure. They had little success with Belgium, either. Germany was convinced that the only possible approach was to attack France through the Low Countries (like in 1914), but they were unable to strike an agreement with Belgium. The Belgian authorities felt that if they were cautious, Hitler would not attack. It thus refused to hold real staff negotiations with Britain and France, on which it would rely if Germany attacked.

The Phony War, 1939 to 1940

There was so little military activity during the winter of 1939-40 that US journalists referred to the struggle as the "Phony War." Warehouses surrounding London were packed with cardboard coffins, preparing for the thousands of people who were supposed to be killed by bombings. City children were moved to the countryside. In the end, both sides refrained from bombing civilian targets, partially to avoid the guilt that would fall on the first to strike cities and partly out of fear of retribution. In a last-ditch effort to rally Germans against Hitler, the British Royal Air Force (RAF) dropped leaflets rather than bombs on Germany.

Only at sea was it clear that this was a serious conflict. Although Germany did not yet have enough U-boats (submarines) to pose a significant threat to Allied shipping, German surface raiders and U-boats scored many key victories. The Graf Spee, a German pocket battleship, had less success. After being cornered off Uruguay by three British cruisers, the ship's skipper sank it in Montevideo harbor following the Battle of the River Plate (13 December 1939).

Hitler desired a genuine, not a phony, war. After the Allies rejected his peace proposals, Hitler prepared for a Western offensive. In October 1939, he issued the Führer Directive No. 6.

An offensive will be organized through Luxembourg, Belgium, and Holland, and it must be launched as soon as feasible... The goal of this offensive will be to defeat the French army and the Allies fighting on their side while also gaining as much territory as possible in Holland, Belgium, and northern France to serve as a base for the successful prosecution of the air and sea war against England...

The German proposal, codenamed Case Yellow, was to be developed in detail by the army's senior leadership. Commander-in-Chief Brauchitsch and his Chief of Staff, General Halder, questioned whether a successful attack could be mounted swiftly. Given that the French army was far stronger than Poland's, it appeared doubtful that blitzkrieg (a term popularized by Western media to describe the speed and devastation of German operations in Poland) would be successful in the West.

Hitler saw things differently. He had little regard for France. The power he most feared was Britain. He intended to strike early because there were just a few British forces in France at the time. In late October, he urged that German soldiers launch an attack in the Ardennes where the French would least expect them. Hitler's generals contended that late October was the incorrect time of year to launch offensive operations.

If German forces were to get through French defenses, they would immediately become bogged down. In November and December, bad weather impeded the implementation of Case Yellow. It was postponed indefinitely in January. This allowed German forces valuable time to work out vulnerabilities discovered during the Polish battle.

The fact that neither Italy nor Japan attempted to exploit the situation at this stage allayed British defense officials' darkest fears. However, Russia acted. In October, the Baltic States (Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania) were forced to accept Soviet garrisons. Stalin also desired a significant portion of Finnish territory. Finland refused. On November 30, Russia invaded Finland.

The "Winter War" was a classic David vs. Goliath conflict. The Finns, whose total strength never exceeded 175,000, fought skillfully and bravely. Soviet troops were unprepared for a winter fight, or for battle in general. (This was partially owing to Stalin's purging of his senior commanders in the late 1930s.) Across the front, the one-million-strong Red Army experienced devastating loss. In December, Allied commanders decided to help Finland.

Daladier believed that Norway and Sweden would let Allied forces pass through their territories and help Finland. Instead, both countries declared their neutrality. Allied leaders decided that if they could not get Scandinavian cooperation, they would act without it. A complex plan to move 100,000 troops to Finland via Norway and Sweden was conceived. The Winter War ended in March 1940, just as the Allied forces were preparing to advance. Soviet soldiers broke past the Finnish defenses. Finland was compelled to give up territory to Russia. The war claimed the lives of 25,000 Finns and 200,000 Russians.

Daladier was discredited. He had announced his goal to help Finland but had failed to do so. On March 20, he was replaced by Paul Reynaud. Reynaud's government was comparable to Daladier's, consisting of a moderate right-left combination. Reynaud desired some Scandinavian action. Swedish supply of iron ore was regarded as critical to Germany's war effort. During the winter, Swedish ore was delivered via the Norwegian port of Narvik and then down the Norwegian coast to Germany. Churchill advocated conquering Narvik. The cabinet rejected this proposal. Instead, it agreed to mine Norwegian waters, thereby cutting off the iron ore route.

On April 8, minelaying commenced. Admiral Raeder, who wanted to acquire Norwegian bases, had long encouraged Hitler to interfere in Norway. Hitler originally dismissed Raeder's advice because he was preoccupied with his plans for the upcoming war on the West. However, he was incensed when, on February 16, a British warship stopped the Altmark in Norwegian waters and rescued some 300 British inmates on board. Hitler, convinced that Britain would soon break Norway's neutrality, directed General Falkenhorst to devise a strategy for an invasion of Norway. Falkenhorst decided that German forces should occupy Denmark as a “land bridge” to Norway.

On April 7, German transport ships carrying 10,000 soldiers departed for Norway. The initiative was a major bet. The Germans needed to seize Norwegian ports and airfields before the Royal Navy could interfere. The British naval command's failure to recognize what was happening provided the Germans valuable time. On April 9, German soldiers struck. Denmark, completely unprepared for war and with no indication of Germany's hostile purpose, simply submitted and became a German protectorate for the duration of the conflict. The Norwegian government hesitated despite being aware of German intentions.

Mobilization orders were sent out by mail. On April 9, German troops quickly took Oslo. Elsewhere, German maritime and airborne forces encountered varied levels of opposition.

The Germans sustained significant naval losses. The cruiser Blücher was sunk by a Norwegian shore battery on April 9. On April 10 and 13, British naval forces sunk ten German destroyers carrying German troops to Narvik. Later in the fight, British torpedoes damaged the German battleships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau. Britain and France rushed troops into Norway. In late April, 25,000 Allied troops besieged 5,000 German infantry and sailors in Narvik, with a further 12,000 men landing near Trondheim.

However, the Allies' campaign was poorly planned and implemented. Without air cover or supplies, Allied forces surrounding Trondheim were quickly compelled to retreat. Meanwhile, German forces steadfastly defended Narvik. The town was not seized by the Allies until May 28th. Events in France resulted in its cancellation on June 8.

Control of Norway offered Germany with valuable naval and air bases from which to attack British ships and the country itself. German morale was undoubtedly boosted by the ease with which they achieved victory. However, the German advances were doubtful. Norway was able to keep significant German forces at bay for the entire conflict.

On May 7-8, the Norwegian campaign was considered in the British House of Commons. The handling of the Norwegian campaign outraged many MPs. Strangely, their target was Chamberlain rather than Churchill, who had been largely responsible for the fiasco.

Many criticized the Prime Minister, believing that he lacked vigor and vision. Approximately 100 Conservative MPs abstained or voted against the government. Chamberlain decided to quit. On May 10, Churchill was appointed leader of a new coalition government. He claimed he had nothing to offer but “blood, toil, tears, and sweat”. His words were appropriate. The initial weeks of his premiership were marked by a succession of Allied military failures.

The Defeat of France, 1940

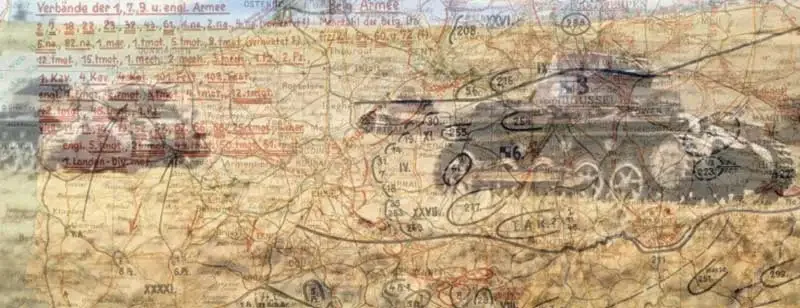

The postponing of Case Yellow in January gave the Germans time to rethink their preparations. Erich von Manstein, General Rundstedt's Chief of Staff, is responsible for the change in plans. Manstein, one of the best military thinkers in the Wehrmacht, contended that a panzer force attacking through the Ardennes might annihilate the Allied lines and gain a decisive victory. Halder was not impressed.

Like most German generals, he believed that the mountainous and wooded Ardennes were inappropriate terrain for panzers. In January, Hitler learned of Manstein's scheme. The two men met in the middle of February. Hitler was soon persuaded by Manstein's ideas, which mirrored his own goals. As a result, the German high command was forced to turn the Manstein-Hitler plan's pieces into a precise order codenamed Sickle Stroke.

Army Group B was to attack Holland and Belgium in an attempt to entice Allied forces northward. Army Group C was supposed to engage the Maginot Line. Army Group A, led by Rundstedt, played a pivotal role. Its 50 infantry and seven panzer divisions were to push through the Ardennes, cross the Meuse, and drive down the River Somme to the shore, trapping Allied forces in Belgium.

Sickle Stroke was a highly risky method. For the Germans to win decisively, the French would have to send a huge number of troops into Belgium, fail to defend the Ardennes and the Meuse, and have no reserves to deal with a German advance. However, German forces had significant advantages. Crucially, the Luftwaffe outperformed the Allies in terms of aircraft quality, experience, and numbers (3,200 to 1,800).

Unlike its British and French counterparts, which had overdiversified in aircraft manufacture, it had focused on acquiring a huge number of a few types of planes, each of which was ideally suited to its specific function. The Messerschmitt 109 was a quick and heavily equipped aircraft. The Stuka was a powerful ground assault dive bomber. The Heinkel 111 was a highly effective bomber. Among the Luftwaffe's senior officers were several outstanding men, including Milch and Kesselring.

The Germans had a further advantage with their tank strategy. Model after model, German tanks were not significantly superior to those of the Allies. Nonetheless, the tanks were assigned to certain panzer units. The panzer divisions, unencumbered by infantry, were trained to emphasize speed and freedom of action.

The French had more tanks than the Germans (3,000 to 2,400), but the majority were scattered irregularly across the French armies. As a result, the French lacked a true equivalent to Army Group A's panzer divisions.

However, French leaders remained confident. That confidence stemmed from the Maginot Line's perceived strength. This enormously expensive defensive system guarded the Franco-German border. However, France lacked the funds to extend the Line along the Franco-Belgian border, which is 402 kilometers (250 miles). Ironically, the Maginot Line provided equal protection for Germany and France. Given that the French had no intention of advancing from the Line to assault Germany, the Germans needed to take few defensive measures. They had much fewer men opposing the Line than the French did.

French authorities anticipated that the Maginot Line would operate as a weir, diverting the German tide into Belgium. In the event of a German attack, Gamelin, the French Commander-in-Chief, planned to send his strongest forces, including the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), into Belgium. These forces would hold the Germans along the Dyle River. Much weaker French troops would be left to defend the River Meuse, which runs opposite the Ardennes.

The BEF was of uneven quality. In 1918, the British army was the most effective fighting machine in the world. Years of defense cuts, however, had reduced the army to the bone and promoted military conservatism. Only five of its 13 divisions in France were regular troops; the rest were Territorial Army (TA) reservists, who were enthusiastic but inexperienced. In May 1940, the 1st Armored Division, Britain's sole tank force, was still unprepared for combat.

The 94 French divisions were a mixed bag, with some good and many awful. The best troops were the ten “active” conscript divisions and the colonial army's seven divisions. Conscript reserve divisions were not particularly good. Many French troops were uncommitted to the cause, divided by French political extremism and fearful of repeating the great sacrifice of 1914-18.

French General Ruby discovered that "every exercise was considered an upset, and all work as a fatigue." After several months of inactivity, nobody believed in the battle anymore. Without the benefit of the Polish campaign, Allied leaders failed to detect or remedy their deficiencies.

Gamelin believed there was little to learn from Poland. This was not his only blunder. In distributing his forces, he left himself with no reserves in case the fight did not go as planned. French intelligence suggested that the Germans might invade through the Ardennes. Gamelin did not rule out this possibility. He had not anticipated the rapidity with which the Germans would move.

The Germans gained an additional edge due to the Allied army's leadership structure. Gamelin retained operational power, but it was delegated first to a Commander Land Forces (General Doumenc) and subsequently to the commander for the north-east, General Georges. Lord Gort, the BEF commander, reported operationally to Georges but ultimately looked to London for orders.

Gamelin's headquarters were in Vincennes, near Paris; Doumenc's were halfway between Georges and Gort in northern France; and the British and French air forces' headquarters were also separated. Personal shortcomings exacerbated structural problems. Gort was a valiant officer who had been awarded the Victoria Cross but was not a good strategist. More crucially, Gamelin possessed minimal military skills.

Chamberlain stated Hitler "had missed the bus" in April 1940. Hitler possessed tanks and aircraft, not buses, and he was prepared to use them. "Gentlemen," Hitler informed his staff on the eve of Case Yellow, "you are about to witness the most famous victory in history!"

The German attack began at 04:30 on May 10. The Luftwaffe bombed airbases in the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. Meanwhile, German ground forces entered the Dutch and Belgian borders. Paratroopers captured significant targets. The most daring of the airborne attacks was on the Belgian fortress of Eben Emael. Some 70 German glider-borne infantry crash-landed on the fort's roof, encircled the defenders within, and, employing concrete-piercing charges, overpowered them in a few hours.

The Dutch were caught off guard by the German invasion. They had not taken part in World War I and had no desire to participate in World War II. They were a German enemy merely because some of their territory provided an easy route around the Belgian water impediments. The Dutch had few forces: 10 army divisions and 125 aircraft.

It appeared that their greatest chance of avoiding defeat was to retreat inside "Fortress Holland" - the waterlogged zone surrounding Amsterdam and Rotterdam - and rely on the network of canals and waterways to delay the invasion. The German air force quickly defeated this tactic. The 22nd Airborne Division landed in the midst of “Fortress Holland” on May 10. Holland surrendered on May 15.

According to plan, Gamelin sent a third of his soldiers to Belgium to support Belgian troops who were already fleeing due to the German onslaught. He thereby fulfilled the Germans' hopes. He failed to recognize that the primary German threat was about to be unleashed further south. From May 10 to 14, seven German panzer divisions, totaling 1,800 tanks, pushed forward nose to tail in the Ardennes defiles.

On May 12, the 7th Panzer Division, led by Rommel, discovered an unprotected weir across the River Meuse, north of Sedan. The next day, Rommel dispatched men across the river to erect pontoon bridges, allowing his tanks to pass. The French counter-attack was ineffective, and the German bridgehead remained intact. Rommel's performance on May 13 was one of the most inspiring of the entire war. At the same time, the main panzer formation of Army Group A launched an attack on Sedan, further south. The French infantry defended inadequately. In contrast, German troops fought valiantly, crossing the Meuse (under heavy fire) and establishing a number of footholds.

French tanks were unable to remove them. German engineers rushed frantically to build pontoon bridges. By May 14, panzers were streaming across the Meuse. Allied planes, savaged by Luftwaffe and anti-aircraft artillery, attempted but failed to destroy the bridges.

The Germans had penetrated the French line at a critical location, necessitating a huge and immediate counterattack. The French generals were not up to the challenge. Efforts to deploy three French armored divisions into position to attack the German flanks failed due to a slew of contradictory orders.

General Heinz Guderian, commander of the 2nd and 10th Panzer Divisions, took advantage of the situation and advanced westward. His tanks met minimal resistance. Thousands of French surrendered rather than fighting. By May 17, Guderian had traveled more than 80 kilometers (50 miles) from Sedan. Further north, Rommel smashed through French lines and advanced westward. He observed: A pandemonium of weapons, tanks, and military vehicles of all kinds, intimately linked with horse-drawn refugee carts, blanketed the roadways and verges...

The French forces were completely taken aback by our unexpected appearance, so they laid down their rifles and marched east alongside our column. No one tried to resist. In two days, Rommel captured 10,000 men and 100 tanks.

The Allies were more concerned with getting out of Belgium than with defending it. Their only hope was to launch a strong counterattack on the panzer corridor's exposed sides. The Luftwaffe's authority over the sky made such strikes impossible to organize. Charles de Gaulle, commander of the French 4th Armored Division, was given orders to attack at Laon.

De Gaulle, a fan of armored combat, eagerly embraced the challenge. His onslaught on May 17th was later used as an example of what the French could have done if all of their generals had been imbued with his attacking zeal. In fact, his offensive was halted by an air strike before he could truly engage the Germans.

On May 15, Reynaud called Churchill and declared, "We have been beaten." "We have lost the battle”. The next day, Churchill flew to Paris to meet with French leaders. Gamelin stated that he lacked the necessary soldiers to stop the German advance. Churchill returned to Britain, vowing to deploy 10 more squadrons of RAF planes to join those already in France. Sir Hugh Dowding, the head of Fighter Command, opposed Churchill's proposal, claiming that 52 squadrons were required to assure Britain's defense.

He was down to 36 and could not afford to lose any more. He convinced the War Cabinet that squadrons should operate over France from British bases. Dowding's actions helped preserve Britain; within a few days, the Germans had overrun the majority of the facilities from which the RAF would have operated in France.

Philippe Petain, the 84-year-old Verdun hero, has now entered the French administration as Reynaud's deputy. Gamelin was replaced by Weygand, Ferdinand Foch's Chief of Staff in 1918, who was seventy-three. Their heroic reputations hinted that something could still be rescued from the jaws of defeat.

On May 20, Guderian's panzer divisions reached Abbeville on the Channel coast, cutting the Allied army into two. Weygand proposed that Allied forces north of the German break-in coordinate attacks on the panzer corridor with French soldiers still operating to the south. His plan never really took off. Many French troops became discouraged. On May 21, a British infantry force with 74 tanks collided with the 7th Panzer Division at Arras. Following some initial success, the onslaught stalled. By May 22, the German spearhead had formed a formidable defensive line that could not be broken. The Allied forces in the north were cut off. It appeared that nothing could save them.

Hitler and Rundstedt were cautious. Both were concerned that the coastal lowlands were unsuitable for tanks. Almost half of the panzers had already broken down, and the remaining ones required urgent maintenance. Furthermore, Göring predicted that the Luftwaffe might defeat the Allied forces in the north. Thus, on May 24, Hitler ordered his panzers to halt. They stayed halted for two days, which may have determined the result of the war. Unbeknownst to Hitler, the British government, in response to a warning from Gort, concluded on May 20 that the BEF could have to be evacuated at Dunkirk and directed the Admiralty to begin constructing a fleet for the task.

Churchill remained hopeful that the BEF could break through the panzer corridor and join the French army south of the Somme. This hope was not practical. On May 23, General Alan Brooke wrote, "Nothing short of a miracle can save the BEF now." That same day, Gort directed his soldiers to retreat towards Dunkirk. This decision saved the BEF.

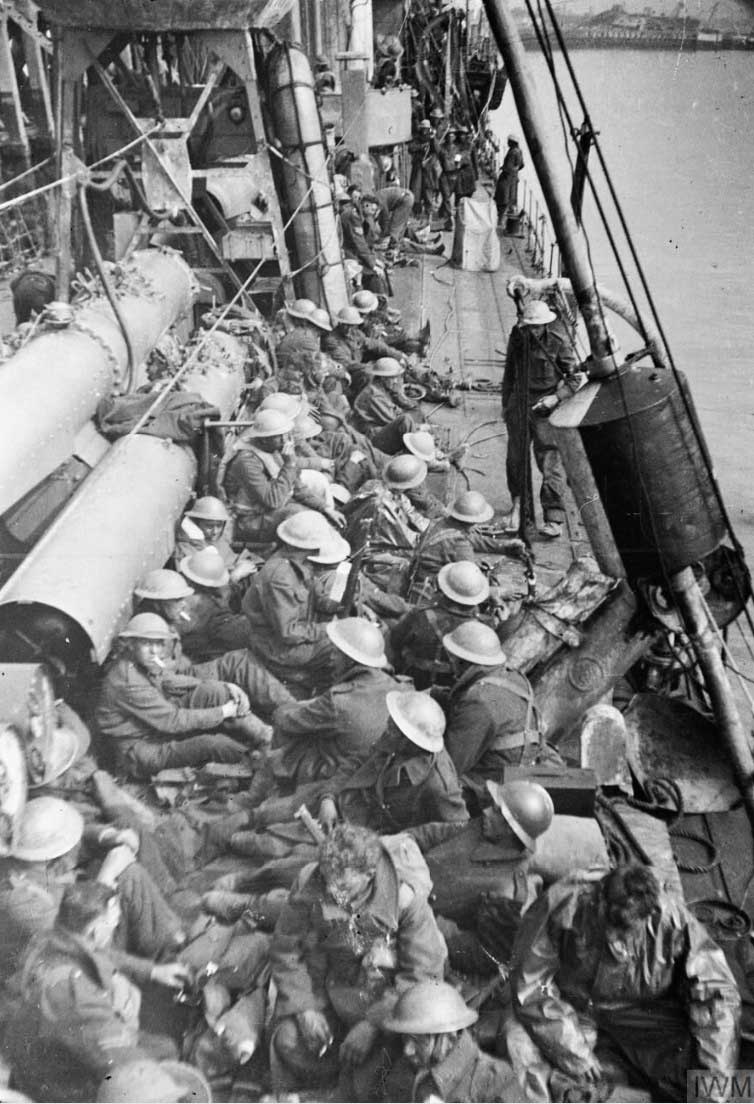

The Disaster at Dunkirk, May 1940

Hitler's "stop order" enabled the BEF and a significant element of the French 1st Army to reach Dunkirk and set up a defensive perimeter around the town. When Hitler's "stop order" was lifted, the part of the Allied army he most wanted to destroy became temporarily safe. The evacuation from the Dunkirk beaches began on May 26. Belgium surrendered on May 27. French troops fought tenaciously to secure the evacuation. The Luftwaffe made every effort to prevent it. Its finest effort fell short.

Despite sinking eight warships in nine days of attack, hundreds of ships were able to approach the coast. Only 8,000 men were evacuated from the Dunkirk beaches on May 26-27. On May 28, as the fleet of navy ships and civilian craft - coastal steamers, pleasure boats, and yachts - increased, 19,000 people boarded. On May 29, 47,000 people were rescued, followed by 68,000 on May 31.

By June 4, when the last ship left Dunkirk, 338,000 Allied men had evacuated. The total includes practically all of the BEF as well as 140,000 French soldiers, the majority of whom were transshipped and returned to French ports in Normandy and Brittany after arriving in England. Dunkirk is sometimes seen as a success. Certainly, the number of men who returned to Britain significantly exceeded even the most hopeful projections at the commencement of the operation. However, as Churchill confessed, "Wars are not won by evacuations."

The evacuated troops had abandoned all of their heavy weapons and transportation, and they were in a condition of chaos. The evacuation also sparked outrage in France. It appeared that the British had abandoned the French.

By early June, the French army had 60 divisions, of which just three were armored. Against them, the Germans sent forth 89 infantry divisions as well as 5 panzer and motorized divisions. The Luftwaffe had approximately 2,500 strike aircraft, whereas France had fewer than 1,000 aircraft. Weygand hoped for a new defensive line that would connect the Channel to the Maginot Line via the rivers Somme and Aisne.

This "Weygand Line" represented (rather than contained) a sequence of "hedgehogs." The "hedgehogs" - villages and woodlands - were to be populated with troops and maintain resistance even when bypassed by enemy spearheads. On June 5, German panzers attacked the line running between Amiens and the coast.

Some French forces battled valiantly, but elsewhere the panzers swiftly found their way into the French rear. On June 9, Guderian's panzers attacked the River Aisne. French resistance eventually crumbled. One German force had now advanced across Normandy into Brittany. Another passed through Champagne, following the Maginot Line in the rear. A third traveled south.

Mussolini, eager to declare war before it ended and deprive him of a share of the glory and benefits, joined Germany's side on June 10. He did not achieve much glory. Four French divisions in southern France easily held their own against 28 Italian divisions. The collapse of the Italian forces highlighted the Wehrmacht's ability.

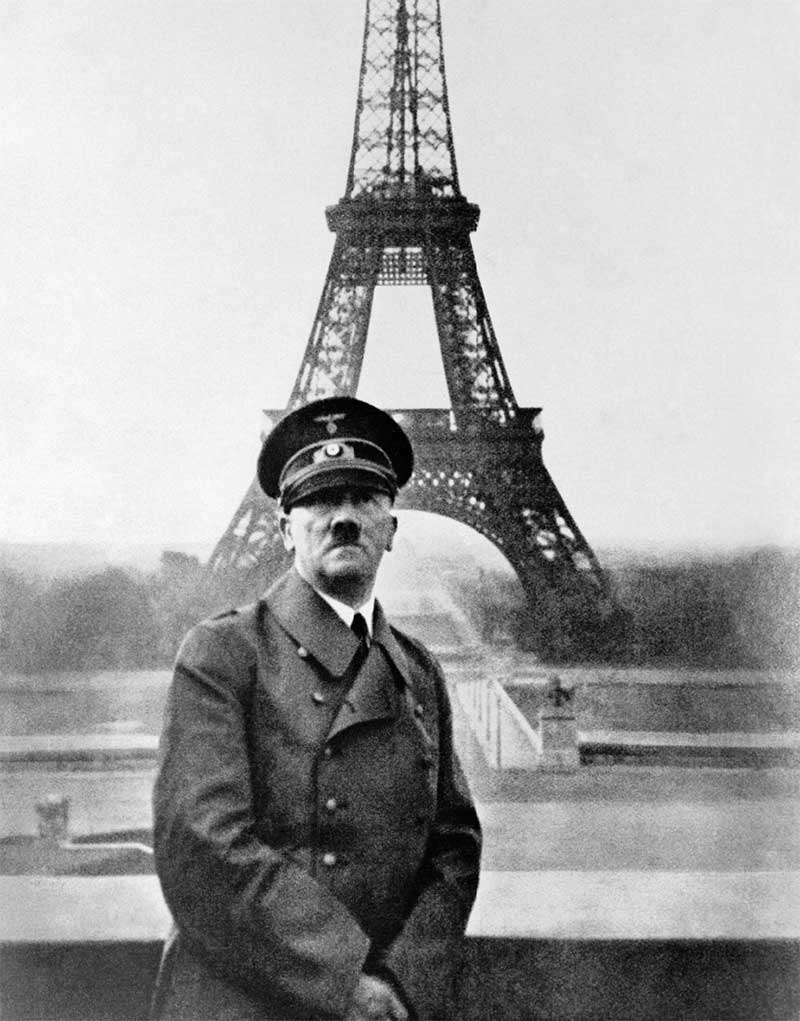

On June 10, Reynaud departed Paris, which was deemed an "open city" to avoid destruction. The first German soldiers landed on June 14 and marched proudly down the Champs-Élysées. Churchill paid repeated visits to France to inspire resistance, but he had little to provide beyond words. On June 16, Britain sought an indissoluble union with France, but it was unsuccessful. Late on June 16, Reynaud resigned.

Petain became France's leader. "It is with a heavy heart," Petain informed the French people, "that I say we must end the fight." On June 21, at Rethondes near Compiegne, French diplomats alighted outside the railway coach in which German delegates had signed the November 1918 Armistice.

The German armistice terms did not allow for negotiations: Petain's government would remain sovereign, but northern and western France would be occupied by German forces. Italy planned to conquer sections of southern France. France was to pay the German "occupation costs." Two million French captives were to remain in German custody.

In short, France would be emasculated and humiliated, just as Hitler felt Germany had been in 1918. (The terms were actually significantly more harsh than those imposed on Germany.) On June 22, the French delegates agreed to the armistice terms.

Conclusion to Blitzkrieg

Nazi Germany had won. The Wehrmacht accomplished in 42 days what German forces had been unable to accomplish during the four years of the 1914–18 war. The German army only lost 27,000 soldiers during the May 10–June 22 campaign, whereas France lost almost 120,000. German achievement was "almost a miracle," according to Guderian. Was that "miracle" more the work of the Germans or the Allies? Many French people still maintain that Britain should not have fled Dunkirk and did not put forth her best effort. With greater validity, the British frequently attribute France's demise to French leadership. Gamelin was not the only one who did it. Numerous French generals who served from 1919 to 1940 were blind to the serious issues with the French army's doctrine and training.

One side of the coin is French miscalculation. Germany, on the other hand, fought a very successful war. Daring strategy had a role in German triumph. Hitler had won at gambling. This did not imply that he was a military genius, as the future would show. Once more, he would wager and lose. German superiority in tactics and armament contributed to their success. The German triumph was made possible by the Luftwaffe and strong panzer divisions. Nevertheless, it was a close-run battle on the banks of the Meuse on May 13 and 14.

In the end, superior leadership, technology, or tactics might not have been as significant as the superior ability, bravery, and morale of the common German soldiers. Better preparation and training, including the experience acquired in Poland, may account for superior skill. It is more difficult to explain superior courage and morale. The majority of German soldiers thought they were waging the good battle for whatever reason (nationalism, ethnic pride, propaganda, etc.). The German success depended heavily on their ability to accept defeat and carry on.

Important Dates

September 1939

Germany and Russia overran Poland: Britain and France did little to help

September 1939 - April1940

The “Phony War”: little happened

November 1939 - March 1940

The Winter War between Russia and Finland

April 1940

German forces overran Denmark and Norway

May 1940

Winston Churchill became British Prime Minister

May - June 1940

German blitzkrieg in the west: German forces invaded northern France and overran Holland and Belgium

May - June 1940

British troops in France were evacuated from Dunkirk

June 1940

- Italy declared war on Britain and France

- German forces occupied Paris

- France surrendered: German forces occupied northern and western France

Read the previous part:

- {{#owner}}

- {{#url}} {{#avatarSrc}}

{{name}} {{/url}} {{^url}} {{#avatar}} {{& avatar}} {{/avatar}} {{name}} {{/url}} - {{/owner}} {{#created}}

- {{created}} {{/created}}