- Military History

- Conflicts & Wars

- World War I

- Involved Nations WWI

- Arabia during World War I - The Arab Revolt - Part 2

Arabia during World War I - The Arab Revolt - Part 2 Opposing Commanders, Armies & Plans

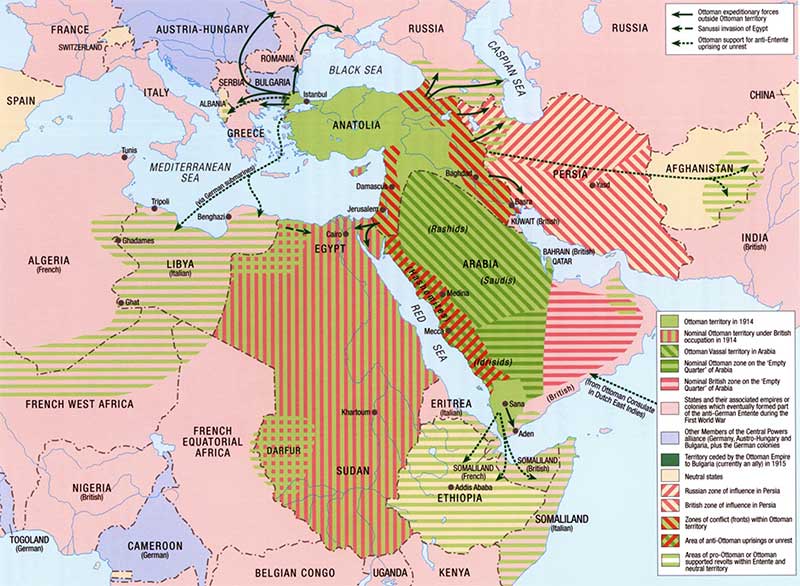

The Arab Revolt was directed against the Muslim Ottoman Empire which had ruled most or the Middle East for centuries. The Revolt also began at the very heart of the Muslim world: in the Hijaz, with its holiest of Muslim cities, Mecca and Medina.

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, the Ottoman state had lost virtually all its European provinces to a wave of remarkably intolerant Balkan nationalism. Not surprisingly, this stimulated a reeling of Turkish national identity within what remained of the Empire, which culminated in the Young Turks Revolution shortly before the Great War.

Index of Content (Part 2)

Opposing Commanders during the Arab Revolt

The Arab Commanders

Ali ibn Hussein (1853-1931) was the originator and the spiritual leader of the Arab Revolt that broke out against Ottoman rule in June 1916. In 1908, he had been appointed as the emir of the holy city of Mecca by the Ottoman sultan. Influenced by nationalistic trends among the Arab peoples, he had begun negotiations with the British command in Cairo in early 1914, before war had even broken out. He established links with the al-Fatat movement in Damascus in early 1915. Following the outbreak of the revolt in 1916, he was proclaimed first as the ‘king of the Arab lands’ and then later as the ‘king of the Hejaz’. He would abdicate in favor of his eldest son, Ali ibn Hussein, in 1924. Owing to the expansion of Saudi power into the Hejaz in 1925, he fled and ended his life in exile. Many Allied officials and officers, including T.E. Lawrence, later commented on Hussein’s considerable abilities as a political leader and motivator of the revolt.

While Hussein acted as titular leader of the Arab Revolt, his sons served as military leaders in the field. His eldest son, the Emir Ali ibn Hussein, served as the leader of the Arab Southern Army and opposed the main Ottoman force at Medina throughout the war. Lawrence commented on his religious zeal and intelligence, and he especially impressed the head of the French mission, Colonel Brémond. He was displaced as ruler of the Hejaz by the forces of Ibn Saud in 1925.

The Emir Abdullah ibn Hussein (1882-1951) commanded the Arab Eastern Army and campaigned against both the Ottoman Army and the forces of Ibn Saud, the great rivals of the Hashemite dynasty in Arabia. Prince Abdullah had also served as his father’s emissary to the British command in Cairo in 1914 and had met with Lord Kitchener. Lawrence found him too politically sophisticated and strong willed to suit British purposes and it seems apparent that Abdullah was a formidable and unshakeable leader of the Hashemite cause. He acted as his father’s Foreign Minister and was later recognized by the British as the king of Transjordan (modern-day Jordan).

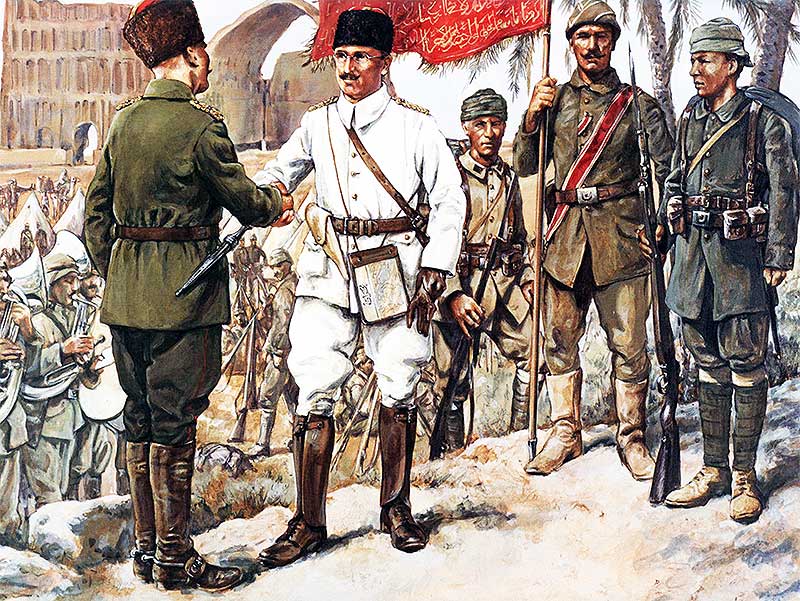

It was, however, Hussein’s third son, the Emir Feisal ibn Hussein (1886-1933), who emerged as the most prominent Arab leader of the revolt, at least from the perspective of later Western historians. He was identified early on by Allied officers as being an inspirational leader and, owing to his own ambitions was, perhaps easier to direct. Lawrence first met him in October 1916 and felt that he best suited the Allied plans, which in reality meant that he was less intractable than his elder brothers. Feisal became the favorite Arab leader of Lawrence, who encouraged him to seek power in Syria. He took command of the Arab Northern Army and led it northwards, facilitated by the capture of Aqaba in 1917. Closely aligned with Lawrence, his army cooperated with General Edmund Allenby’s forces during the last campaigns of 1918. Feisal’s great skill was in motivating and uniting the Arab tribes under his command, while he also maintained the momentum of the Arab northern campaign.

Arab officers who had previously served in the Ottoman Army commanded the units of the Arab Regular Army. These men included some very able officers, such as Jafar Pasha al-Askari (1885-1936), a Kurd from Mesopotamia and a former Ottoman officer. He had undergone training in Germany and had played a major role in the Senussi Revolt of 1916, before being captured by the British. At the outbreak of the Arab Revolt, he was a POW in Cairo but was eventually persuaded to join and lead the Arab Regular Army. He joined the campaign in 1917 and immediately displayed his tactical and administrative experience. Jafar Pasha was also an extremely tough and pragmatic commander, at one point advocating the use of mustard gas during the siege of Ma’an in 1918.

One of the first former Ottoman officers to serve the Arab cause was Aziz Ali al-Masri, a Circassian from Egypt who had also served in the Senussi Revolt before being persuaded to join the Arab cause. He joined the Arab forces in July 1916 and was an advocate of guerrilla warfare. Al-Masri recommended the formation of a ‘flying column’, which could then be used against the railway and also to push northwards into Syria. In fact, this was exactly what Feisal and Lawrence would later do. He was appointed as commander of the Arab Regular Army in 1916, but al-Masri was not popular with Hussein, who viewed the former Ottoman officers with some suspicion, and he was later sacked, being replaced by Jafar Pasha. As the first commander of the Sharifian Army, al-Masri actually was the founding father of that army, yet he has been largely forgotten by history.

Nuri as-Sa’id (1888-1958) was also a former Ottoman officer and in 1916 he commanded the regular troops of Prince Ali’s Southern Arab Army. A talented artillery officer, he later served as chief of staff of the Arab Northern Army and served under Jafar Pasha.

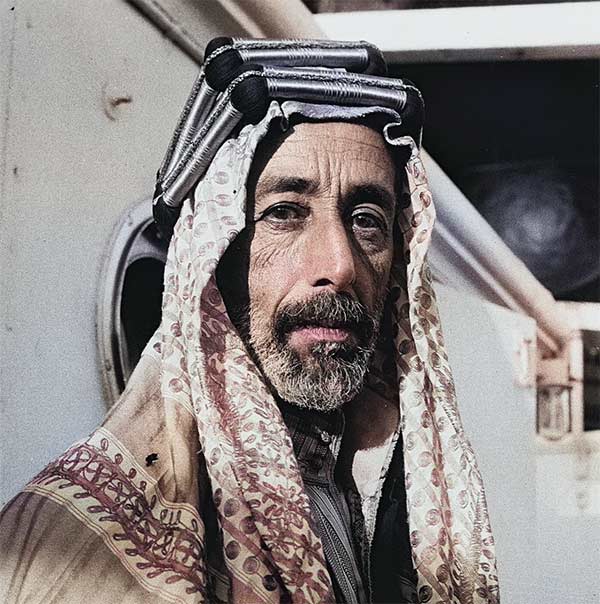

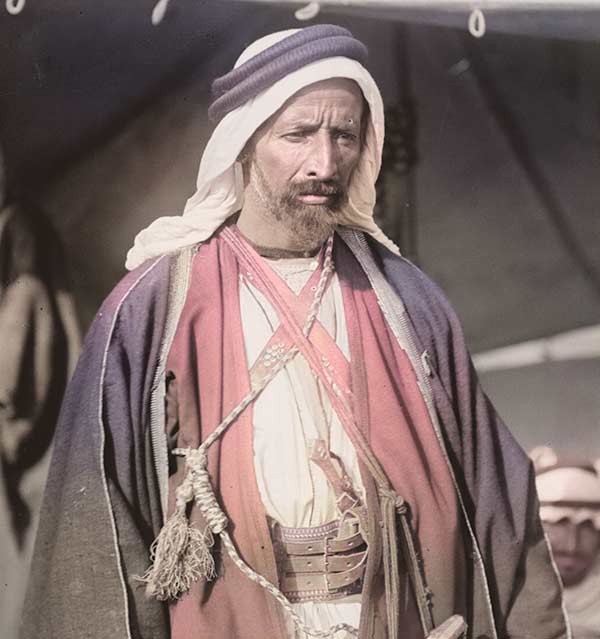

The irregular forces of the Arab armies comprised tribesmen who were commanded by their tribal chiefs. These included many leaders who showed a natural talent for guerrilla warfare. Perhaps the most famous of these was Auda abu Tayi (c.1870-1924), the hereditary chieftain of the Howeitat tribe and a close associate of Lawrence. He commanded the warlike tribesmen of the Abu Tayi branch of the Howeitat, who were concentrated near Ma’an. His support was being crucial by both sides and the Turks courted him throughout the war, even after he had proclaimed for the Hashemite cause and despite having been outlawed for killing two tax collectors. In a campaign in which larger-than-life figures seem to have abounded, Auda still stands out as a dramatic and charismatic leader, claiming to have killed 75 Arabs and countless Turks by his own hand in battle. There were many other tribal leaders who also played a major role in the revolt but have been largely forgotten. These included Sharif Nasir, who took part in the attack on Aqaba in 1917 and was also at the action at Tafila in 1918. He rose to command the irregular force of the Northern Arab Army. It is impossible in the space of this article to enumerate the many other tribal leaders who played a part in ending Ottoman power in Arabia.

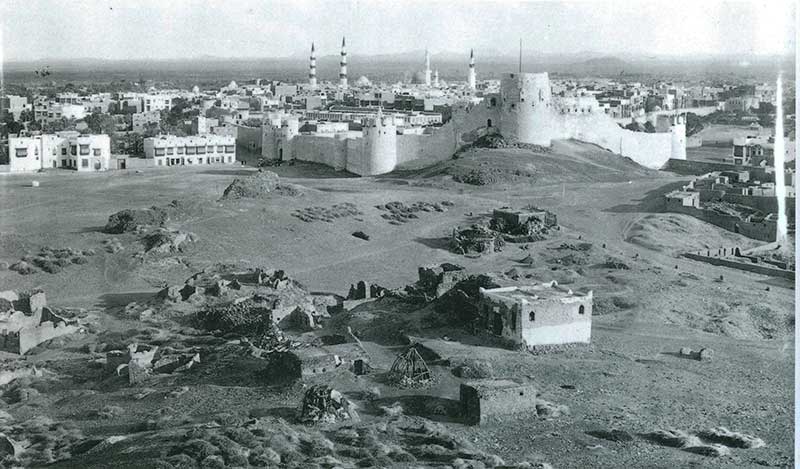

It must be pointed out that there were other Arab forces operating in Arabia that were not aligned with the Hashemite cause. Abdul Aziz ibn Saud (1880-1953) was also supported by the British and was a very capable military leader. He was the sultan of Najd in central Arabia and also controlled the coastal region of al Hasa. Ibn Saud numbered among his supporters members of the puritanical Wahabi sect, and during the war he opposed Ottoman forces and also pro-Ottoman tribes. He would emerge in the post-war years as a major force in Arabia and would eventually thwart Hashemite plans.

Some Arab tribes also remained loyal to the Ottomans. The most significant of these were the Shammar tribes, led by Ibn Rashid. Ibn Rashid effectively controlled north central Arabia with his power base at Ha’il. The Ottoman administration provided him with over 12,000 rifles and money and, while not incredibly active during the war, his forces acted as an effective counterbalance to both the Hashemite armies and also those of Ibn Saud. For the Arab Revolt, the very existence of this pro-Ottoman force had strategic implications and obliged the Hashemites to keep troops in the south to counter it.

The Allied Commanders

The British Commanders

At the outbreak of the Arab Revolt in 1916, the commander of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force was General Sir Archibald Murray (1860-1945), who had begun the war as chief of staff to the BEF in France. Having suffered from a stress-induced nervous breakdown, he had become Commander-in-Chief Egypt in 1916. For the first year of its existence, therefore, the Arab Revolt relied on his patronage for arms, money, and men, either in the shape of British Army officers or Egyptian troops.

Murray’s role in the revolt’s history has been the focus of much criticism, and he is often portrayed as a conventional, unimaginative general.

There were mitigating factors to his behavior, however. He has been criticized for his unwillingness to send troops to aid the revolt, yet it must be pointed out that his command was constantly being stripped of forces for the Western Front. His progress through Sinai has been derided for its snail-like pace but, Murray was hampered by huge logistical difficulties and the apparent stagnation of British strategy was because of these problems. In ideological terms, it must be said that Murray disliked ‘sideshows’. This dislike had a sound basis, as he had seen sideshows like the Gallipoli and Mesopotamia campaigns descend into failure. These failures had always been achieved at substantial cost. He had a profound distrust of the amateur officers, political officers and Arabists who seemed determined to start another sideshow in Arabia. Having failed in two successive battles at Gaza, Murray was replaced in June 1917.

Murray’s successor was General Sir Edmund Allenby (1861-1936). Allenby has emerged from World War I as one of the great heroes of British arms. He had seen service in the Second Anglo-Boer War of 1899-1902 and in 1914 served with the BEF in France as GOC of the Cavalry Division. In 1915 he was given command of the Third Army, but his later career on the Western Front was extremely mixed. After what was considered being a poor performance at the battle of Arras in April 1917, he was removed from command. In June 1917, he was appointed to command the Egyptian Expeditionary Force.

Allenby’s appointment came at a crucial time for the EEF, which had been demoralized owing to the failures of recent campaigns. He reorganized his force and restored morale. Allenby also recognized the potential of the Arab Revolt as both a means of tying down Ottoman troops in Arabia, but also perhaps as a way of harassing the enemy by sending raids behind the Turkish left flank. His enthusiasm for the revolt was confirmed by Lawrence’s capture of Aqaba, which occurred in July 1917, just after he had taken command. Allenby encouraged Feisal and Lawrence to take the revolt northwards and also supplied the Arab Army with armored cars and air support. The success of the Arab army in 1917 and 1918 justified his support.

In the months that followed the outbreak of the revolt, several other British officers were sent to Arabia to assist the Hashemite rebellion. Most of them were serving in Arabia months before Lawrence had even left his desk in Cairo. In June 1916, Colonel Cyril Wilson (1873-1938), a former governor of the Sudan, was sent from Cairo under the cover of acting as a ‘pilgrimage officer’. He headed the British mission at Jiddah and supervised the landing of military supplies while also liaising with the Hashemite leaders.

Another senior officer with the British mission was Colonel Pierce C. Joyce (1878-1965), who was a veteran of the Boer War and had been serving on the staff in Cairo since 1907. Joyce took command of the British base in Rabegh in December 1916 and would later command at Aqaba. From there, he became the principal organizer of logistical arrangements for Lawrence’s expeditions into Palestine and Syria. Joyce was later appointed as head of the British military mission to the Arab Northern Army, codenamed Operation Hedgehog.

There were many other British officers who served in the initial stages of the revolt. They included Colonel Stewart Francis Newcombe (1878-1956), an officer with the Royal Engineers who had been associated with Lawrence before the war when he undertook a survey of the Sinai. Newcombe recognized the importance of the Hejaz Railway and embarked on a series of raids against the railway, before being captured by the Turks in October 1917. An entire cast of other officers served in the campaign between 1916 and 1918. To name them all would cause an exhaustive list.

To a certain extent, all of those who took part in the revolt, whether Arabs or Allied officers, have been overshadowed by Thomas Edward (T. E.) Lawrence (1888-1935). His actions in the war, and his post-war fame, have resulted in his becoming a modern legend. Born in 1888 in Wales, he was one of five illegitimate sons born to Sir Thomas Chapman, an Anglo-Irish baronet, and Ms. Sarah Lawrence. He was educated at Jesus College, Oxford, and received a first-class degree, having traveled extensively in the Middle East for his BA dissertation on Crusader castles. Between 1911 and 1914, he worked on the British Museum’s excavations at Carchemish in Syria. Also, in 1913 he had assisted Captain (later Colonel) Newcombe in a survey of the Sinai. Presumably, this expedition was for geographical purposes, but in reality, this was an intelligence gathering expedition. Commissioned as a temporary officer on the outbreak of war, he had been posted to the military intelligence office at GHQ in Cairo.

His fellow officers often viewed Lawrence with some disdain. He was an amateur soldier, but highly intelligent and opinionated. Some described him as an insufferable know-it-all. In his appearance, he was often unkempt and improperly dressed by military standards. Yet he had knowledge of Arab customs and language, and he also had some knowledge of areas that were now firmly ‘behind enemy lines’. Losing his two brothers on the Western Front as well spurred Lawrence to get back at the enemy. While he was not planning a significant role for himself within the Arab Revolt in 1916, a combination of factors would thrust tremendous responsibilities upon his shoulders. Because of his actions in this campaign, Lawrence would emerge after the war as one of the most iconic and enigmatic figures of the 20th century.

The French Commanders

In the months that followed the revolt, the French also established a military mission in order to aid the Arab cause. This was officially termed the ‘Military Mission to Egypt’ and had its base at Port said, with the first members of the mission arriving in Alexandria in September 1916. At its height, the French mission numbered almost 1,100 officers and men.

The original commander of the French mission was Colonel Edouard Brémond, an officer of considerable experience who had campaigned in North Africa before commanding an infantry battalion on the Western Front. He was aided in his work by several other experienced officers and together they built up a healthy working relationship with Sharif Hussein and his sons, emirs Ali and Abdullah. For this reason, most of the French effort was focused on the southern campaign around Mecca and Medina.

To some extent, the French had a considerable advantage over the British in that they could field Muslim officers from their North African regiments. These included Colonel Cadi and Capitaine Muhammad Ould Ali Raho (1877-1919). Capitaine Raho, of the 2e Régiment de Spahis Aljérien, was an officer of vast experience. Having enlisted as a trooper in 1896, by 1903 he had served in 15 campaigns in North Africa. Raho was one of the first Allied officers to carry out missions against the Hejaz Railway, such as the mission in February 1917. The French mission also included Capitaine Laurnet Depui, a hero of Verdun who later converted to Islam, and Adjutant Claude Prost, who became Sharif Hussein’s foster brother.

The French officer who achieved the greatest prominence in the revolt was Capitaine Rosario Pisani, who was attached to the Arab Northern Army. Pisani originally operated with a small party of engineers and carried out attacks on the railway. He later commanded an artillery battery and accompanied Lawrence on some of the later campaigns of 1917 and 1918. A close associate of Feisal, he would later support the Arab cause at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919.

Finally, it must also be pointed out that, because of the long-term implications of this campaign, there were several political officials of both the British and the French governments who were involved closely with efforts to direct the revolt. These ranged from senior civil servants such as Sir Mark Sykes and Georges Picot, to local officials such as Sir Reginald Wingate, Governor of the Sudan. Other political figures who played an important role were Sir Henry McMahon, British High Commissioner in Egypt, and Ronald Storrs. The policies devised by such men would have a direct bearing on the conduct of the campaign.

The Ottoman Commanders

The most senior Ottoman officer in the campaign against the Arab Revolt was Mehmed Cemal Pasha, ‘Büyük’ (1872-1922). He had been a veteran member of the Young Turks movement and on the outbreak of war was a senior figure in the government, holding the office of Minister of Marine. During the war, he held two other senior military offices alongside his ministry. He was military governor of Ottoman Syria and as such had been responsible for the crackdown against Arab nationalists in the first years of the war. As governor, his responsibility included Palestine and stretched as far as Arabia. Cemal Pasha was also the commander of the Ottoman Fourth Army and had been the instigator of the unsuccessful attack on the Suez Canal in February 1915. A highly intelligent and somewhat ruthless commander, he forbade the withdrawal of troops from Arabia.

In Arabia itself, the most senior commander was General Hamid Fakhreddin (‘Fakhri’) Pasha (1868-1948). An officer of considerable experience and ability, he became the de facto supreme commander in Arabia, as he commanded the largest and most effective force from Medina. Like Cemal Pasha, he held dual rules, acting both as governor of Medina and military commander. His defense of Medina was inspired, and he tied down two of the three Arab armies for much of the war.

It is difficult to get a genuine sense of documenting the other Ottoman commanders in the field because of the lack of Turkish sources in English. It must also be said that many English-language sources often pay little attention to these men. It can be seen, however, that officers such as Mehmed Cemal Pasha (Küçük or Üçüncü), the commanding officer of the 1st Kuvve-i Mürettebe, which handled railway security, carried out their duties commendably despite the difficulties they faced in trying to counter a campaign of railway sabotage in a theater that covered a vast area.

Opposing Armies during the Arab Revolt

The Arab Army

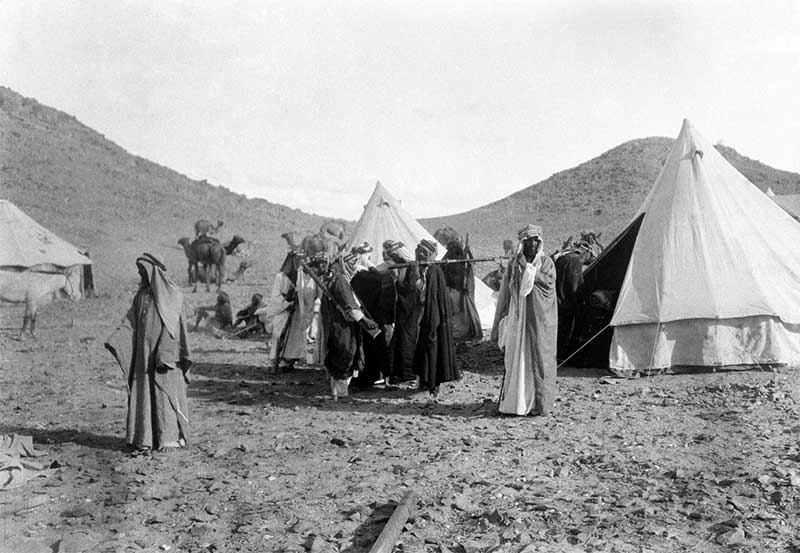

The Hashemite Army that instigated the Arab Revolt was composed of tribesmen from both the settled and nomadic Arab tribes. It is difficult to get an accurate assessment of how large this army was. Some estimates suggest 30,000 tribesmen who took part in the initial actions around Mecca, Medina and Ta’if.

Not all of these tribesmen matched the stereotype that is held in the west of dashing, camel-mounted warriors. Many of the first followers of Sharif Hussein and his sons were from the highlands of the Hejaz. They were simple farmers, often impoverished, whose harsh rural existence hardened them for life on campaign.

More tribesmen joined from the nomadic tribes and, as the campaign became more mobile, they played an increasingly important role. To give a full listing of all the nomadic tribes that joined the revolt would be impossible in the scope of this article. They included tribesmen of the Harith, the Bani ’Ali, the Bani ’Atiya, the Bani Salem, the Juhaynah, the Utaybah and the Howeitat, among many others. In geographical terms, their tribal heartlands spanned a large area from the southern Hejaz as far northwards as modern-day Jordan. As the campaign moved into Palestine and Syria in 1917 and 1918, tribesmen were recruited from these areas. Later, recruits included Arab farmers from the Hauran area and men from the Christian minorities.

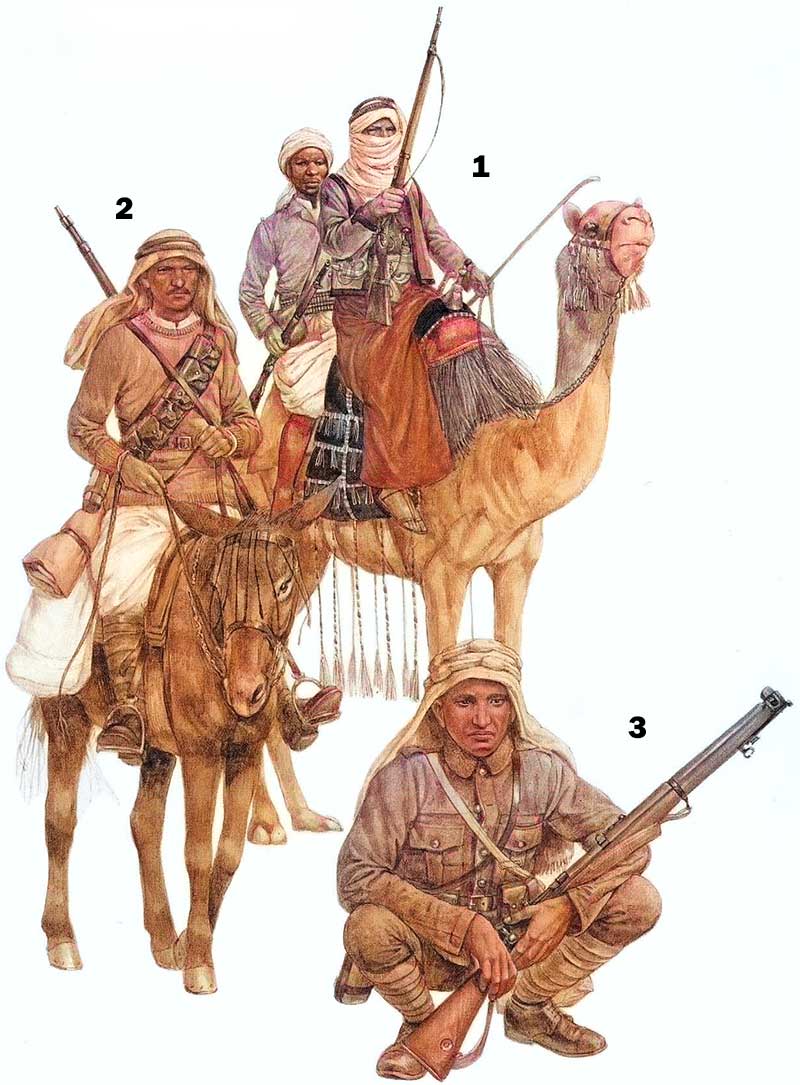

Using such men to engage in a guerrilla war against the Ottomans made eminent good sense, as for centuries tribal warfare had essentially been guerrilla warfare. The men of the Arab irregular army could cover vast distances on camelback and then dismount to fight on foot. They could survive in areas where survival was thought to be impossible. The Arab irregulars also proved to be excellent shots, especially as they were increasingly re-armed with modern rifles.

There were also disadvantages in using these men. They were untrained and often lacked discipline. In raids on Ottoman positions, they excelled, but they could not be used in major offensive or defensive actions. Many were reluctant to move outside their own tribal areas, which meant that, as the campaign moved northwards, new followers had to be recruited and paid. The payment of the irregular army represented an enormous investment by the Allied governments. Payment had to be in gold coins, which were shipped across the Red Sea. By the end of 1916, the French Government had spent 1.25 million gold francs in Arabia. At that stage, the monthly allowance to support the Emir Feisal’s Arab Northern Army cost the British £30,000 in gold coin. By September 1918, the monthly British allowance to the Hashemite cause was £220,000.

At the outbreak of the revolt, it also became apparent that these tribesmen would have to be entirely re-armed. While the British command in Egypt had sent some weapons across the Red Sea before the outbreak of the revolt, it would appear that most tribesmen were still armed with muzzle-loading jazail muskets. In the short term, a re-arming programme got under way using captured Ottoman weapons and also a quantity of Japanese Arisaka rifles supplied by the British. Later in the campaign, an effort was made to supply all tribesmen with a British service rifle, usually the excellent Short Magazine Lee Enfield (SMLE) with a caliber of .303in. The widespread issue of this weapon increased the effectiveness and firepower of the Arab irregulars and made it easier for the British to supply both ammunition and spare parts. In some late 1918 photographs, it can be seen that the tribesmen were still using different rifles, so re-supply with the SMLE never reached all the irregulars. Other photographs show Arab tribesmen with long Lee Enfield rifles.

The Arab irregulars were also issued with support weapons. Their style of warfare negated the use of heavy weapons, so they were issued with light machine guns only. These included both the French Hotchkiss and the British Lewis gun, both of which fell into the ‘light machine gun’ category. The larger Vickers or Maxim guns would not seem to have been issued, which probably made sense as they were heavier weapons that used tripods and water-cooling systems. They would not have been easy to transport, and the water-cooling system presented obvious problems in a desert campaign, but still Lawrence mentions their use by tribesmen during the Tafila action of January 1918.

While the Arab Regular Army, which will be discussed below, wore a uniform, the irregulars kept their own Arab clothing. This made eminent good sense as these clothes were suitable for camel riding and life in the desert, both factors that played a part in the life of tribal irregulars. As headdress they wore the Arab keffiyah head cloth and they also wore loose cotton trousers, Arab cloaks (aba) and also tunics or the dishdashah, an ankle-length garment in loose cotton. Colors of these garments would differ from tribe to tribe, creating a very non-uniform appearance when different tribal groupings campaigned together.

Within the tribal irregulars, a specific contingent deserves special mention. These tribesmen came from the Agayl, who formed a distinct warrior class in Arab society. The Agayl had their homeland in the Hejaz and the Najd regions and were predominantly settled tribesmen. They were famous as camel-traders and as such, their young men traveled throughout Arabia. It was also their tradition of working as mercenaries and they enjoyed a considerable reputation as camel-mounted warriors. They played an invaluable part in the Arab Revolt. As mercenaries, they would travel outside of their tribal homelands and, as a result, these experienced desert fighters traveled with the Arab Northern Army as it moved northwards. They were particularly valued among the Hashemite leaders, and many were recruited into personal bodyguards: Lawrence himself later recruited from among the Agayl for his own bodyguard.

While the irregular tribal contingent was excellent for guerrilla warfare, it was recognized early on that a regular force would also have to be raised to provide a hard core of fighters for the Arab Revolt. This force came to be known as the Regular Arab Army or the Sharifian Army. At the outbreak of the revolt there was a source of recruits close at hand as the British had captured thousands of Ottoman soldiers in campaigns in Sinai, Libya and Mesopotamia. These Ottoman POWs included Arab officers and soldiers. Many of the officers, who included men of Iraqi or Syrian birth, were sympathetic to the Arab cause. Among the enlisted men, there were also men of Arab birth. In late 1916, the first 1,000 men were sent to the Hejaz, and these men formed the first detachment of the Sharifian Army. They were experienced, disciplined soldiers and as such, they played a major part in the revolt, taking part in several conventional actions such as the attacks around Ma’an in April 1918.

While there were Regular Army contingents with all the Arab armies, it was with the Arab Northern Army that they were most numerous. In this army, they numbered around 2,000 men, all ranks. The infantry was formed into two primary units, alternatively referred to as ‘divisions’ or ‘brigades’. The infantry numbered around 1,500-1,600 men and they were supported by a camel corps, mule-mounted infantry, artillery and also machine-gun detachments. They were armed with SMLE rifles and given standard British uniforms but wore an Arab keffiyah headdress rather than British headgear. The lack of artillery dogged all the Arab armies, but especially the Arab Northern Army throughout the campaign. The amount of artillery was never adequate. Some Turkish mountain guns were captured at Ta’if at the beginning of the campaign and to these the British added some obsolete artillery from the Egyptian Army. The French supplied both a field and a mountain battery, and further Turkish guns were captured at Tafila in early 1918. Yet the lack of modern artillery hampered the operations of the Arab Northern Army. Machine guns were, however, supplied in large numbers and, as with the irregular contingent, these were of the Hotchkiss or Lewis types and also the heavier Vickers gun.

The Arab armies comprised therefore irregular and regular units. From its inception, the revolt also had a European contingent made up of British and French personnel. Initially, the Allied powers were represented by an officer contingent that acted as political officers, training officers and who also controlled the supply of material. Engineering officers helped improve the defenses of the towns that were held by Hashemite forces. While such activities were continued throughout the war, British and French officers paid an increasingly important role. They took part in the campaign against the railway and soon European NCOs were also training Arab troops in using light machine guns, artillery, and Stokes mortars. The French had a training mission based at Mecca, made up of Muslim officers and NCOs from North Africa, while British officers fulfilled the same role with the Arab Northern Army.

By late 1917, the European contingent had redoubled. The British Army had supplied the Arab Northern Army with a squadron of Rolls-Royce armored cars and also Talbot cars, some of which mounted 10-pounder guns. A flight of aircraft had been attached. Initially, these were of obsolescent BE2s, but later some of the excellent Bristol F2 Fighters were attached to the northern force. The addition of such units increased the military potential of the Arab Northern Army, and they played an important role in the later campaigns of the war.

Using European troops en masse remained a tough point, as the Hashemite leaders did not want to be seen using infidel western troops in their campaign. Even Allied officers recognized the sensitivities of sending European troops to campaign in the most holy region of the Muslim world. In the early months of the revolt, the British sent Egyptian troops to circumvent this issue while the French could rely on Muslim troops of their own. Later, troops from the Indian Army would serve alongside the Arab Northern Army and these would include Gurkhas. In 1918, a force of the Imperial Camel Corps (raised from British yeomanry units) was also added. Therefore, by the end of the war, the Arab Northern Army was perhaps one of the most cosmopolitan forces to take part in the war.

The Ottoman Army

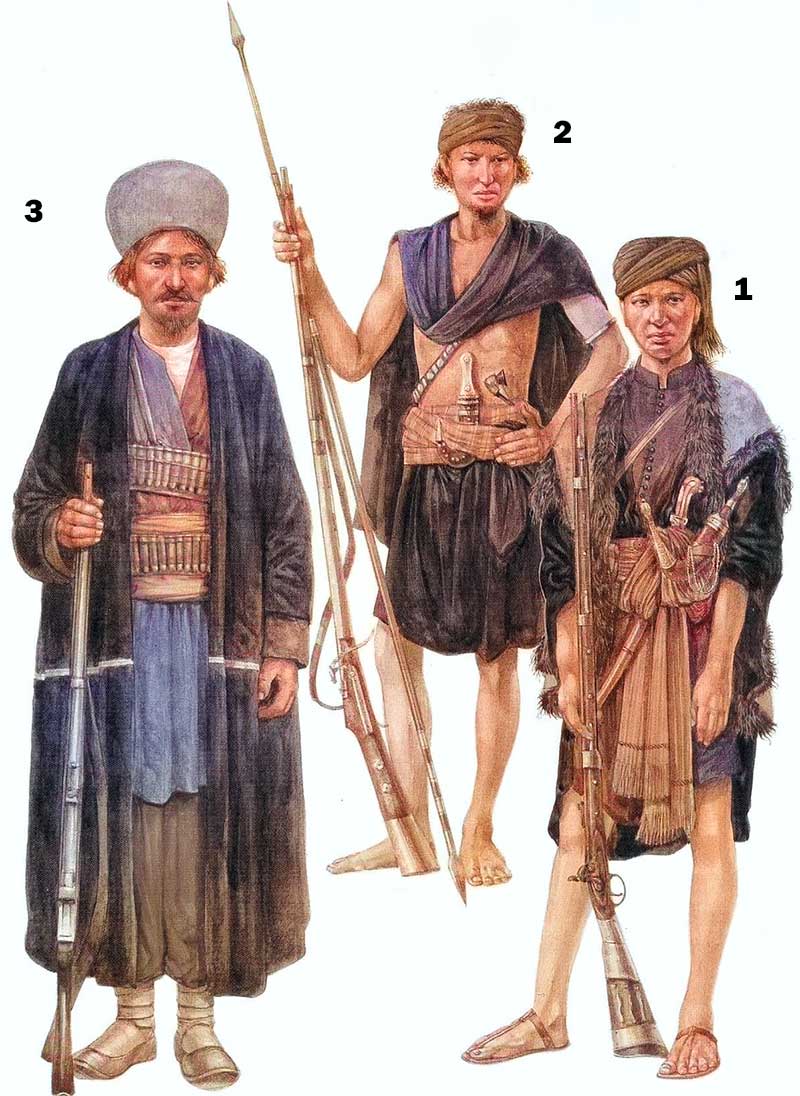

There is a common misconception that the Ottoman Army of World War I was entirely ‘propped up’ by German forces. There had indeed been a huge pre-war reform of the Ottoman Army and the influence of the German military mission of General Liman von Sanders was significant, both in the re-equipping of the army and in its training. German influence has been exaggerated and nowhere is this more true than on the Arabian front, where German influence was minimal.

It is also assumed that the Ottoman Army in Arabia was on the verge of collapse for much of the war. But it can be shown that new formations were raised and that the Turkish Army was capable of offensive operations in Arabia for much of the war. At its height, the Ottoman Army in Arabia numbered over 20,000 men. This force was formed into conventional divisions and composite units that were formed to react against the Arab Revolt and also attacks on the railway in particular. They were supported by artillery, cavalry, mule-mounted infantry, and other logistical and medical units. The Ottoman gendarmerie also provided a useful auxiliary force and could be used for garrison duties, while the Ottoman camel-mounted infantry was effective. At the beginning of the campaign, some planes of the Ottoman Air Force were rushed to the Hejaz. These would later be supported by further planes from the Ottoman and German air forces. They had considerable effect when used against tribal forces.

The individual Turkish soldier had proved his worth in a series of campaigns before 1916. While at the beginning of the war, Allied officers had not rated Turkish troops highly, they had since been forced to revise this opinion radically. The campaigns in Gallipoli and Mesopotamia illustrated the fighting qualities and tenacity of the Turkish infantryman, or ‘Johnny Turk’ as he came to be known. Attitudes to the Ottoman officer corps had also been revised, considering these campaigns.

At the outbreak of the war, the VIII Corps of the Ottoman Fourth Army defended Arabia, but in the prelude to the outbreak of the revolt, further Ottoman troops had been sent southwards to Medina. In response to the revolt, new formations were raised, including the 58th Infantry Division, under Lieutenant-Colonel Ali Necib Pasha, the 1st Kuvve-i Mürettebe (Provisional Force) commanded by General Mehmed Cemal Pasha (Küçük) and the Hicaz Kuvvei Seferiyesi (‘Expeditionary Force of the Hejaz’) commanded by General Fakhri Pasha. These new formations were based at Ma’an and Medina and were tasked with keeping the railway open and also operating against the Arab armies. The 2nd Kuvve-i Mürettebe had been raised by 1917 and was based at Tabuk.

The composition of the Ottoman Army in Arabia was also interesting, as it contained several Arab units. While both the Hejaz and the Najd regions were exempt from military conscription, large numbers of Arabs fought with the Ottoman Army on all fronts, including Arabia. There is no sign that these Arab units were prone to higher rates of desertion.

The great difficulty for the Ottoman commanders in Arabia was one of supply. Owing to the limited infrastructure in this vast area, a great reliance was placed on the Hejaz Railway. Road networks were not good and transport equipment was less than adequate. This placed huge limitations on the Ottoman commanders, and it can be shown that several expeditions against the Arabs ended prematurely because of logistical problems rather than enemy opposition. The re-supply and re-equipping of Ottoman units was therefore uneven throughout the war. By the end of the war, it was becoming increasingly difficult to re-equip and re-clothe troops on all fronts and shortages became especially acute in Arabia. Ottoman troops continued to recount themselves until the end of the war in Arabia and, sometimes, even beyond that.

For Ottoman troops, the Arab Revolt could mean operating in the field with one of the larger formations sent out against the Arabs. Many times, it meant long periods spent on garrison duty. If the soldier was lucky, this was in one of the large centers of Ottoman power, such as Ma’an. It could also mean long and dangerous periods of garrison duty in blockhouses along the Hejaz Railway. Ottoman soldiers’ weapons could include any of several rifles from the Turkish Mauser models M1893 and M1903 to German Mauser M1898. Some troops were issued with obsolete rifles, such as the Turkish Mauser M1887. Despite these potential shortcomings, the Ottoman Army was to perform well, owing largely to the military qualities and inherent tenaciousness of its officers and men. It must also be pointed out, however, that the Ottoman reaction to revolt was often robust, to say the least. Accounts of the massacre of civilians are still much debated, but it would seem to be true that Ottoman soldiers engaged in reprisals frequently during the revolt.

Opposing Plans during the Arab Revolt

The Arab Plan

The plan of the Hashemite leaders in 1916 was simple in principle but hugely difficult to execute. Their basic aim was to rid Arabia of both the Ottoman Army and the administration it supported. To complete this task would have required a large, disciplined army with a well-organized logistical supply network. It would also have required support from all the tribes of Arabia. Sharif Hussein and the Hashemite leaders had none of these things, and this led to huge difficulties at both the planning and operational levels of the revolt. These difficulties were compounded by problems in communications and also personality clashes within the Hashemite command. Ultimately, what they could plan for in the initial stages of the revolt was a limited operation, with limited goals in mind.

There has been so much speculation and assumption made since 1916 about Arab intentions, and it is sometimes difficult to assess just what was being planned for at the beginning of the revolt. But analysis of events can lead to conclusions about what the Arab leaders thought they could realistically achieve.

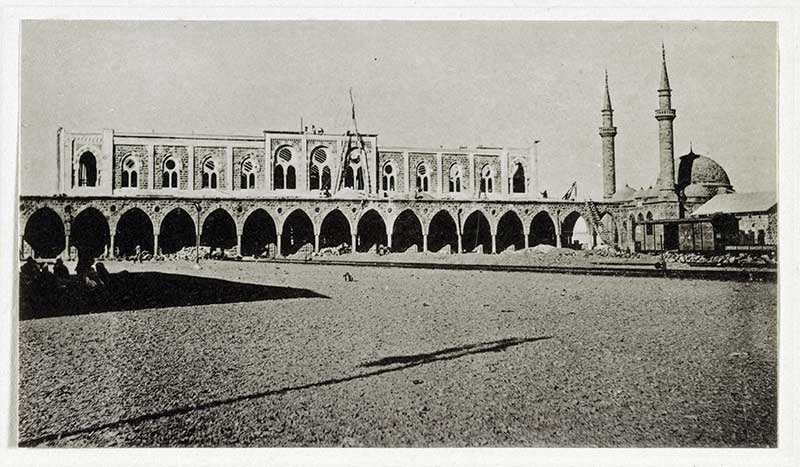

One of their first priorities in their planning had to be the taking of the holy cities of Mecca and Medina. While Sharif Hussein was the emir of Mecca, he needed to convert his currency as a spiritual leader into real political power. Medina, as the resting place of the Prophet Muhammad, was an equally important location. If the Hashemites held the two most important locations in Islam, they could then be viewed as the de facto leaders of the Islamic religion.

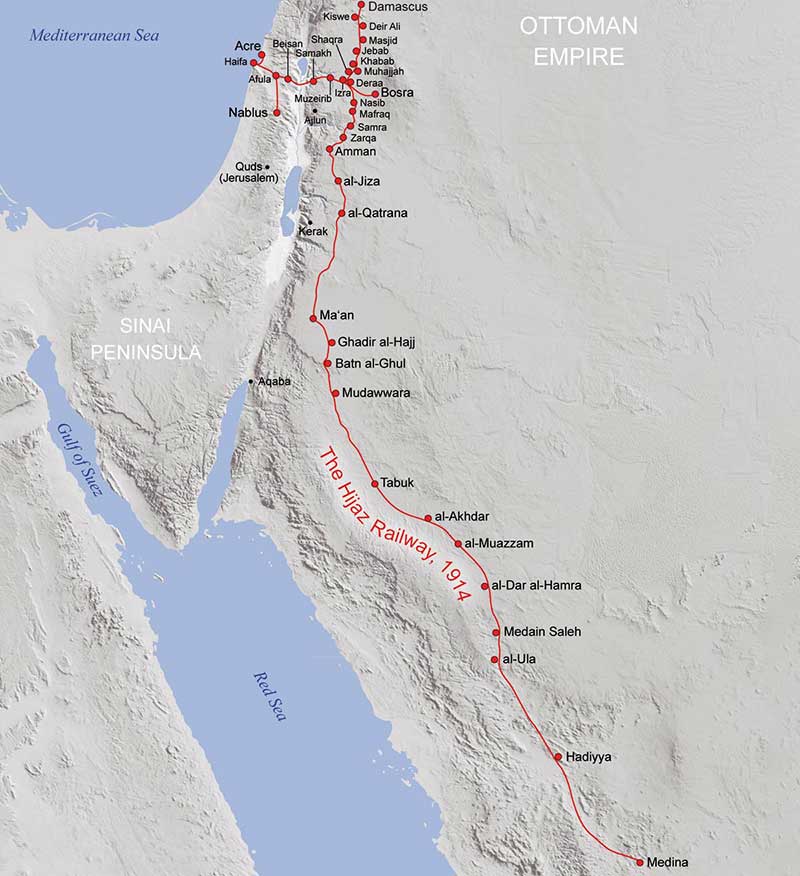

Medina was also of strategic importance, as it was the terminus of the Hejaz Railway. It connected Arabia with the nearest major center of the Ottoman administration in Damascus and from there back to Constantinople. It was the location of a large garrison and was also the location to which reinforcements would be sent. In military terms therefore, Medina was of prime importance. Ta’if also emerged in Hashemite plans as a major aim. In the summer months, the main garrison of Mecca was moved there to escape the worst of the heat during this season. In order to be certain of Mecca, the garrison at Ta’if had also to be attacked and neutralized.

Implicit in Arab plans was the hope that they would be further supported by Britain and perhaps France. For this to happen, the coastal towns on the Red Sea also would have to be taken and Jiddah, Rabegh and Yanbu became objectives as well. If these towns were secured, further military supplies could be landed. In the worst-case scenario, they could be used as points of evacuation. Jiddah could serve Mecca while Rabegh and Yanbu were close to Medina.

From the beginning of the campaign, the Arabs were also aware of the importance of the Hejaz Railway. Indeed, the importance of the railway to Turkish operations had long been recognized, one Turkish source claiming that attacks by Arab nationalists were not uncommon before 1914. As part of the plan for the revolt, the railway would have to be attacked and cut to prevent, or at least delay, Ottoman reinforcements being sent south into Arabia. The line north of Medina would be the target for such attacks.

The Hashemite plan was, therefore, both simple and elaborate. It required the simultaneous attack on several strategic locations. It required the seizing of ports, and it required the interdiction of supplies and reinforcements along the Hejaz Railway. For a well-trained and disciplined force, this would have presented difficulties. It also meant that, rather than concentrating their forces, the Arab leaders had to dissipate them in a series of attacks over a wide area.

Failing to take Medina had serious strategic ramifications, and these will be discussed later. Say that this had a major effect on future Arab plans, as two Arab armies had to remain near Medina and Mecca to counter Turkish counterattacks from Medina. That these Hashemite armies had to counter the forces of both Ibn Saud and Ibn Rashid also affected planning, as it became imperative to hold these forces in the south to maintain Hashemite power in Mecca. From late 1916, therefore, keeping control of these parts of the Hejaz played a large part in Hashemite planning. It is fitting at this point also to examine the plans of Prince Feisal and his Arab Northern Army. As the third son of Sharif Hussein, it was made increasingly clear to him by his father and elder brothers after the outbreak of the revolt that he could expect little in any post-war settlement in Arabia. Because of this, and encouraged by T. E. Lawrence, he looked northwards, hoping to give scope to his ambitions. The hope of being able to become ruler of Palestine or Syria prompted him to move northwards to Wejh and then Aqaba. For Feisal, the success of Allenby’s campaigns in 1917 and 1918 was crucial for his own plans.

These forces underpinned the most dramatic phase of the Arab Revolt as the Arab Northern Army played a major part in British plans from the summer of 1917.

The British Plan

From June 1916, the Arab Revolt played a part in British plans. Depending on who was Commander-in-chief in Egypt, these plans represented two very different strategic mindsets. Up to his replacement in June 1917, General Murray had a limited but perhaps realistic view of what the Arabs could do to support British plans. At the outbreak of the revolt, Murray’s long-term strategy was to move the British Army through Sinai with the intention of both advancing into Palestine and pushing the Turks back from the Suez Canal Zone.

How could the Arabs aid this plan? For Murray, they represented an untried and untrained force, but if supplied with military material, they could become a nuisance to the Turks and thus hold down troops in Arabia. These troops would otherwise have been used in Palestine. Ultimately, therefore, Murray saw them as having ‘nuisance value’ only and while he continued to send supplies to the Arabs, he repeatedly refused to send troops. His vision was to limit the revolt to the Hejaz, intending to hold Turkish troops in the Hejaz. It was left to General Allenby to recognize the full potential of the Arab Revolt and see how it could aid his long-term strategy for taking Palestine and Syria.

As it was, the campaign in Arabia was indeed tying down large numbers of Ottoman troops. Following the capture of Aqaba in July 1917, Allenby sent more and more military material to Feisal’s Arab Northern Army, recognizing that the attacks on the railway and more general raiding represented a massive return on his investment. Based on reports sent to Cairo by Lawrence and other senior British officers, he came to recognize that the Emir Feisal’s hopes of advancing into Syria could fit nicely into his own plans. For this reason, the Arab Army, based at Aqaba, played a major part in British planning throughout 1917 and 1918. In future operations, they would divert the enemy, destroy his rail links and, in the last campaign of 1918, harass the Turkish left flank as Allenby advanced into Syria.

The Ottoman Plan

By 1916, the Ottoman Army had resisted attacks by Allied armies in Gallipoli, Mesopotamia and along its eastern borders with Russia. From June 1916, the Ottoman command had to deal with internal revolt in Arabia. The Turkish plan in Arabia from 1916 also developed in the two years that followed.

In its earliest form, Turkish plans were quite simple; this was a revolt that had to be suppressed and the captured towns had to be recaptured. The initial Turkish reaction was optimistic, and it was felt that this could be achieved easily, especially because a new emir of Mecca was appointed (Sharif Ali Haidar) and sent south to Medina. They believed that his lack of experience would help their cause. Later on, they realized things were not that easy as resistance and strength of the opposing units were much higher than expected; quickly realizing the initial plans would prove a very difficult undertaking.

The initial Ottoman countermoves failed to come to grips with the Arab enemy in order to destroy it. In the vast spaces of southern Arabia, the tribal enemy seemed to melt away. They did not offer battle in the classic sense, and the Ottoman Army needed a large logistical system to maintain itself in the field. The details of the Ottoman efforts to end the rebellion will be discussed later in the text. It suffices to point out here that, having failed to put it down in 1916, the main strategic concern became the garrison at Medina. By its very existence, it kept large Arab forces in the area. It also became the focus of a build-up of troops and the plan was that further decisive expeditions would later take place against the Arabs.

The crucial strategic consideration for the Turks came to be the Hejaz Railway. It had to be kept open so that the Medina garrison, and also lesser garrisons along the line, could survive. It had to be kept open to allow for the possibility of later military action. In short, it was necessary for the Ottoman Army to survive in Arabia and for there to be any possibility of any re-establishment of Ottoman rule. Yet maintaining this line would occupy much of the time and resources of Turkish planners. While the Turks remained in Medina, they also represented the extreme left flank of the Turkish line. This was a consideration for both Murray and Allenby as they made plans to push into Palestine as, regardless of how far any British force might advance, the garrison at Medina would still pose a threat as it made up a large enemy force behind the British right, albeit at some considerable distance. Even when hampered by the cutting of the railway, such a large Turkish contingent in Arabia remained a factor in British planning.

Further to the south, the Ottoman Army maintained a division in the Yemen. While the history of the war in the Yemen cannot be examined here in any detail, it must be pointed out that the strategic situation demanded that Medina be kept. Considering the Royal Navy’s control of the Red Sea, Medina represented the nearest source of practical aid for the garrison in the Yemen.

In Ottoman plans, therefore, the maintenance of the railway line and the retention of Medina formed a major part of the long-term strategy in Arabia.

The Political Plan

The plans of government officials also played a part in shaping the Arab Revolt. Decisions made in London and Paris, even before the revolt had broken out, had long-term ramifications for Arabia.

The imminent collapse of the Ottoman Empire had been predicted since the mid-19th century. Following Turkey’s entry into the war, government officials of the Entente powers discussed how Turkish territory should be divided after its defeat. Of course, these discussions in no way reflected military reality. While British and French forces were suffering defeats in Gallipoli and Mesopotamia, senior civil servants met to decide how former Ottoman territory would be ruled. The two most prominent officials in this process were Sir Mark Sykes for Britain and M. Georges Picot for France.

Their negotiations continued throughout late 1915 and in February 1916, a broad agreement was reached. This agreement was ratified in May 1916 in what came to be known as the ‘Sykes-Picot Agreement’. Under its terms, France would take control of Syria, Lebanon, and Turkish Cilicia. Under its mandate, Britain was to control Mesopotamia, Transjordan, and Palestine. Russia was to take control of the Armenian and Kurdish territories along Turkey’s north-eastern border. The holy city of Jerusalem was to be governed by an international commission, while Arabia was to receive a certain level of independence.

These plans did not reflect the aspirations of the Arab peoples. Also, they did not reflect the promises later made by British and French officers on behalf of their governments. As Lawrence later put it, the Arabs were ‘fighting for us on a lie’. As news of these political plans was leaked, they had a real impact on the Allied-Arab relationship and endangered the future of the Arab Revolt.

Read the previous part:

Read the next part:

- {{#owner}}

- {{#url}} {{#avatarSrc}}

{{name}} {{/url}} {{^url}} {{#avatar}} {{& avatar}} {{/avatar}} {{name}} {{/url}} - {{/owner}} {{#created}}

- {{created}} {{/created}}