- Military History

- Conflicts & Wars

- World War I

- History & Theaters WWI

- World War I - Eastern Front (1914–1918)

World War I - Eastern Front (1914–1918) A conflict that ended the czarist rule in Russia

Although the western front of World War I has received the most attention from historians, the war on the eastern front was a tremendously costly, large-scale conflict, which did much to precipitate the Russian revolutions of 1917 and bring an end to czarist rule.

Index of content

- Eastern Front Strategies

- The Battle of Stallupönen

- The Battle of Gumbinnen

- The Battle of Tannenberg

- The Battle of the Masurian Lakes

- The Austrian Front

- Invasion of the Polish Salient

- The Battle of Rava-Ruska

- Germany Rescues its Ally

- The Battle of Lodz

- Germany Reinforces the East

- The Carpathian Action

- The Battle of Bolimov

- The Second Battle of the Masurian Lakes (the Winter Battle)

- The Gorlice Breakthrough

- The Battle of Lake Naroch

- The Brusilov Offensive

- Romania enters the War

- The Russian Revolutions

- The Second Brusilov Offensive

- The Riga Offensive

- Russias Separate Peace

- Principal Combatants (Eastern Front only)

- Principal Theaters (Eastern Front only)

At the beginning of the war, the Western Allied powers took great comfort in the existence of what they called the “Russian steamroller.” They believed that the sheer numbers of Russian troops would make up an irresistible force. On the eve of war, the Russian army numbered 1.4 million men, and mobilization added another 3.1 million. During the war, 12 million Russians would serve. More than half this number, 6.7 million men, would be killed or wounded before the revolutionary communist government made a “separate peace” with Germany at the start of 1918.

What the Allies had not counted on was the impact on the Russian army of poor leadership and inadequate equipment, as well as an outmoded and poorly developed infrastructure, including a sparse and inefficient railway network. Most of all, they had not realized the depth and breadth of the Russian revolutionary movement, which would ultimately undermine the already faltering Russian military apparatus. Population and manpower Russia had in abundance. Equipment, however, was in short supply, and effective political and military leadership was almost totally absent.

Eastern Front Strategies

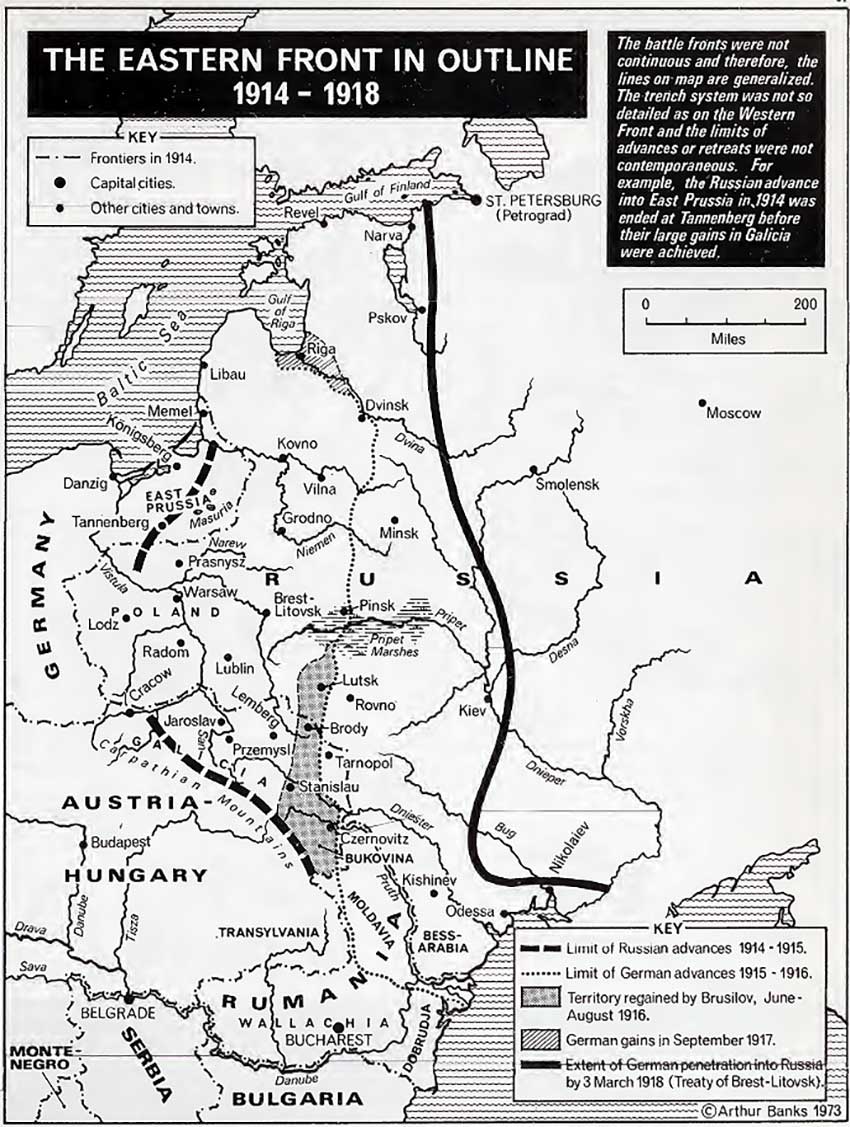

From the German perspective, Russian Poland posed a threat of invasion to East Prussia, but it was also highly vulnerable to invasion by Germany from the northwest and by Austria-Hungary from the southwest. Many in Germany desired the conquest of Russian Poland as a buffer between Germany and Russia, but the German plan called for the conquest of France before embarking on an offensive war against Russia. For this reason, they pursued it a defensive holding action against Russia until they had achieved victory on the western front.

The German high command believed this strategy would succeed, estimating that it would take many weeks for the lumbering Russian army to mobilize, especially given the poor state of Russian railways. Germany’s chief ally, Austria-Hungary, regarded the eastern front differently. Much more of Austria-Hungary’s frontier with Russia was farther east than Germany’s, and the eastern fringes of the Austro-Hungarian Empire were populated by Slav minorities, which felt much greater affinity for the Russians than for the Austrians. Austrian authorities feared that the Slav minorities would enthusiastically receive a Russian offensive, and the already creaky Austro-Hungarian Empire would face imminent peril. For this reason, Austria-Hungary wanted immediate, vigorous action to check any Russian offensive.

Russia, in fact, was eager to prosecute a war in the name of Slavic unity. Czarists saw war as an antidote to Russia’s flagging international prestige and to its growing revolutionary movement. Russia did not want to fight Germany, however, but resolved to concentrate all immediate forces against Austria-Hungary, leaving the German front alone until mobilization was complete. Russia’s French allies objected to this strategy, however, and insisted on Russian action against Germany to relieve some of the pressure on the western front.

In the end, they deployed two Russian armies against the Germans in East Prussia, while they sent another four armies against the Austro-Hungarians in Galicia.

The Battle of Stallupönen

What France demanded of Russia was wholly unrealistic. Russia lacked the technology, leadership, and flexibility to wage a two-front war. Before the war, Russia’s Stavka (General Staff) replied to French insistence that 900,000 men be available by the 14th day after mobilization that such a deployment would consume at least 20 days. In the end, however, the Russians promised deployment by day 15, a promise that would prove a dream.

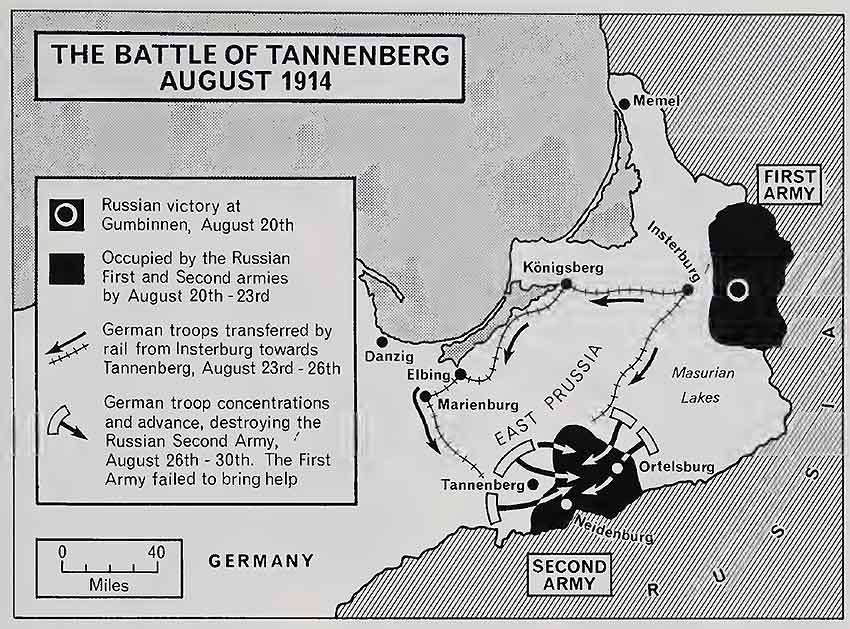

Although the Russian Northwest Army Group, under General Yakov G. Jilinsky, marched west on August 12, 1914, actually earlier than the schedule promised, it stepped off prematurely, without adequate supply or communications. On the 12th, the First Russian Army, under General Pavel V. Rennenkampf (1854–1918), crossed into East Prussia. The Second Army, under Alexander V. Samsonov (1859–1914) was supposed to keep pace with Rennenkampf’s command, so that the two armies could converge in an attack on the German Eighth Army, a force they collectively outnumbered almost three to one.

Although the Russian plan was sound, it faltered in execution, providing an opportunity for the outnumbered German Eighth Army, under General Max von Prittwitz (1848–1917), to fight a delaying action. At Stallupönen, about 100 miles east of Eighth Army headquarters and near the East Prussian frontier with Russian Poland, one of Prittwitz’s most aggressive corps commanders, Hermann von François (1856–1933), disobeyed standing orders to avoid decisive engagement by launching an offensive against Rennenkampf’s center. François inflicted 3,000 casualties and pushed the Russians back across the frontier into Russian Poland. Defeat at the Battle of Stallupönen stunned Rennenkampf into near-paralysis.

The Battle of Gumbinnen

German victory at Stallupönen prompted the usually cautious Prittwitz to take the offensive. He was further encouraged because the literacy level of Russian troops was so low that commanders had taken to transmit radio messages in the clear rather than in code. The result was that Prittwitz and his officers received Russian orders simultaneously with the Russian officers. Based on intelligence gathered, Prittwitz attacked with three corps at the village of Gumbinnen on August 20. The corps led by François was triumphant, but the other two German corps failed to take Rennenkampf’s center.

The Battle of Gumbinnen was, therefore, a draw. Worse, the results of the engagement reawakened the customary caution of Prittwitz, who now proposed a general retreat. His staff protested; one of his staff officers, Lieutenant Colonel Max Hoffmann (1869–1927), made the counterproposal of attacking Samsonov’s left flank near Tannenberg, on East Prussia’s southern frontier with Galicia. Although Prittwitz reluctantly agreed, the German overall chief of staff, Helmuth von Moltke (1848–1916), realized that Prittwitz was not the man for the job. He called the redoubtable Paul von Hindenburg (1847–1934) out of retirement to assume command of the Eighth Army and assigned the brilliant Erich Ludendorff (1865–1937) a hero of the assault against Verdun on the western front, as his chief of staff.

This command team would prove to be the most effective of the entire war. On August 22, Ludendorff devised a plan that, coincidentally, duplicated what Hoffmann had proposed to Prittwitz. Elements would attack Samsonov’s Russian Second Army while others remained farther east to delay Rennenkampf’s First Army. It was a classic strategy of divide and conquer, prevent Rennenkampf and Samsonov from joining forces, and their armies could be defeated, even by inferior numbers.

The Battle of Tannenberg

On August 25, 1914, Erich Ludendorff received two intercepted messages. One was from General Rennenkampf, laying out the marching orders of the entire Russian Second Army. The uncoded message revealed the distance separating the Second and First Armies, and it revealed that Rennenkampf would not pose a threat to the German position for at least another day. The second message, from General Samsonov, betrayed the Russian general’s mistaken belief that the German army was retreating from him. The message also laid out just how he planned to pursue the enemy he believed he had defeated.

Armed with the intercepted messages, Ludendorff could attack Samsonov in confidence that Rennenkampf could not come to his colleague’s aid. The absence of Rennenkampf would allow the Germans to trap Samsonov’s Second Army in a catastrophic double envelopment. Believing himself in an excellent position for victory, Samsonov deployed on his extreme right (the northeast end of the Russian Second Army) his VI Corps, leaving that unit entirely isolated as he pushed the main body of his army westward for an assault on the Germans.

Not only did this movement leave VI Corps vulnerable, it also drew the Second Army farther from, not closer to, Rennenkampf’s First Army. Samsonov was intent on placing himself between the Vistula River and what he believed was the retreating German army. In pursuing this error, Samsonov took his army farther and farther from sources of supply. His troops grew hungry and exhausted.

On August 26, Samsonov’s VI Corps on the right was 80 kilometers (50 miles) from I Corps (and other elements) on the left. Between these, Samsonov had arrayed the rest of his army. However, Samsonov realized that his right flank was vulnerable. He had planned to pursue the retreating German army into Germany itself. Faltering, he ordered the VI Corps to hold fast, to protect the army. But then he renewed his confidence and pushed the advance forward, only to countermand once again his order and instruct the VI Corps to hold its position on the right. But it was too late. VI Corps was already on the move, and the right flank of the entire Russian Second Army was exposed.

As the Russian VI Corps marched toward Samsonov’s center, unaware that they had changed this order, its commander received word that they had sighted German forces 10 kilometers (six miles) behind it, to the north. Part of the VI Corps was ordered to countermarch to meet the Germans. The unit was attacked, and the VI Corps began taking devastating casualties. The command structure broke down; by the morning of August 27, what was left of VI Corps was a panic-stricken rabble. Quickly, the right wing of Samsonov’s army collapsed, and the Russian center came under heavy attack. The Russian XIII Corps left the railway center of Allenstein to assist in the action at the Russian center. This left a wide gap at Allenstein, a perfect opportunity for the Germans.

Samsonov was being enveloped, but instead of cutting his losses in retreat, and preserving some part of his arm, he reengaged with the object of holding off the Germans with his center corps until Rennenkampf arrived to turn the tide.

At 4 A.M. on August 27, General François began an artillery barrage against the Russian I Corps at Usdau. The shelling was sufficient to rout the hungry and weary Russians, which left Samsonov’s left flank completely exposed. Samsonov’s only hope was to hold out with his two center corps until the arrival of Rennenkampf’s First Army. A combination of Rennenkampf’s indolence and incompetent orders from the Russian supreme command ensured that Rennenkampf would not arrive, and during August 27–28, 300,000 men were desperately engaged in one of the most violent battles in the history of modern warfare.

By August 28, the Russian I Corps had collapsed on Samsonov’s left, and VI Corps had been destroyed on the right. Both flanks of the Russian Second Army had been turned. As night fell on the 28th, Samsonov attempted to rally his troops through personal command. When this failed, he ordered a general retreat of what remained of the Russian Second Army. The Germans hammered away at the withdrawing forces during August 29–30.

Tannenberg was no longer a battle, but a slaughter. Some 30,000 Russians perished or were wounded at Tannenberg (compared to between 10,000 and 15,000 German casualties). Among the last of them was General Samsonov, who committed suicide on the night of August 29.

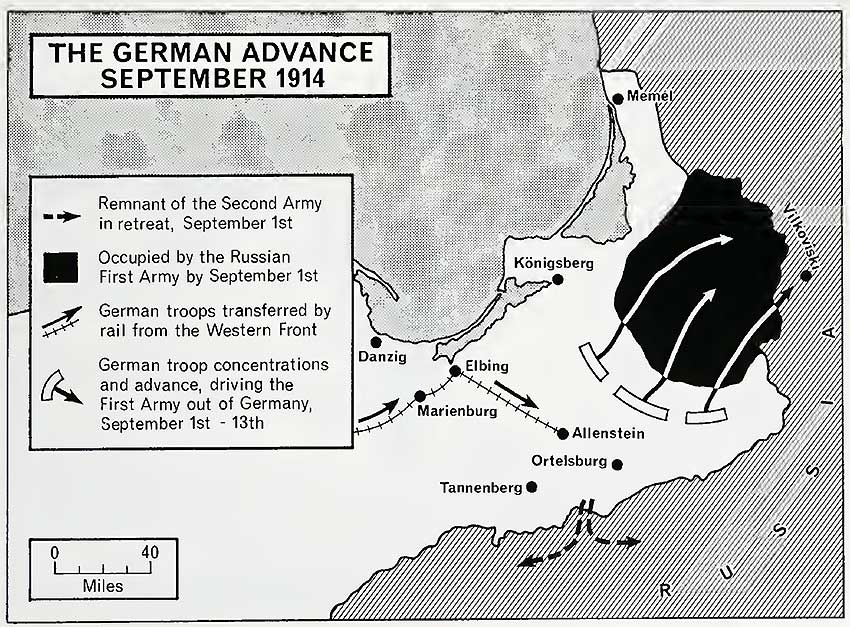

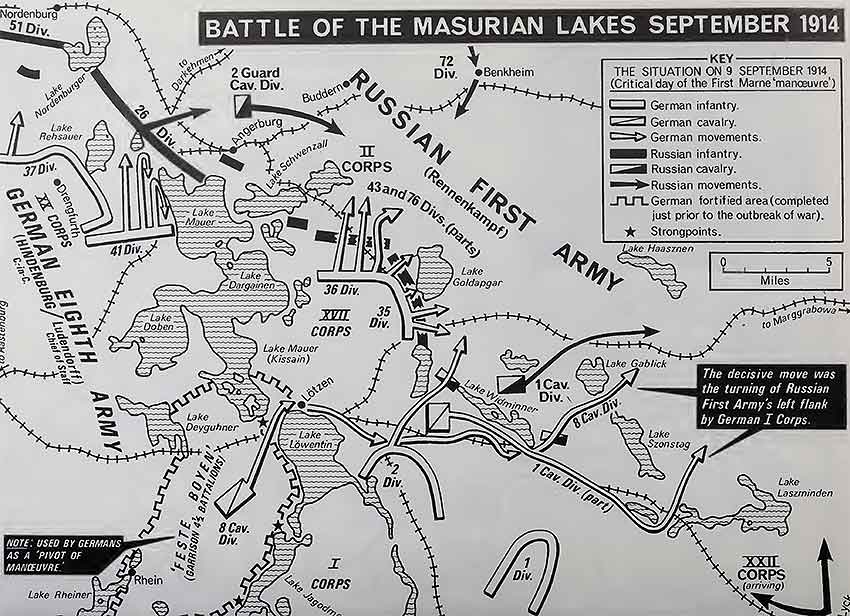

The Battle of the Masurian Lakes

In 1914, the Masurian Lake district was in the southwestern corner of East Prussia, a region of some 2,000 separate lakes in marshy ground. Rennenkampf deployed the Russian First Army here, well north of Tannenberg. The now reinforced German Eighth Army, having crushed Samsonov, marched to meet Rennenkampf. On September 5, the German Eighth Army attacked the southern end of the Russian First Army. In response, Rennenkampf ordered a general withdrawal on September 9. François’s I Corps pursued the retreating Rennenkampf, and Rennenkampf counterattacked the German center on September 10.

The attack halted the Eighth Army for two days, buying the Russians enough time to escape the fate of double envelopment that had destroyed the Second Army at Tannenberg. Rennenkampf had lost about as many men as Samsonov had lost at Tannenberg, about 125,000 killed, wounded, missing, or captured. German losses may have numbered 40,000, but the last of the Russian invaders had been cleared out of East Prussia, and from these two defeats, at Tannenberg and the Masurian Lakes, Russia would never recover.

The Austrian Front

Austria-Hungary had conducted the first operations of World War I with the bombardment of Belgrade, capital of Serbia, on July 29, 1914, but it was August 12–21 before the attack was followed up by an invasion of Serbia with some 200,000 Austro-Hungarian troops under the command of General Oskar Potiorek. Expecting easy victory, fiercely determined Serbs met the Austro-Hungarians under Marshal Radomir Putnik, who sent the Austro-Hungarian Army fleeing back across the River Drina.

Invasion of the Polish Salient

On August 23, General Count Conrad von Hötzendorf (1852–1925), the Austro-Hungarian chief of staff, prepared to lead the First, Fourth, and Third Austro-Hungarian armies (positioned from west to east) in an invasion of the Polish Salient, a portion of Russian Poland projecting westward below East Prussia and above Galicia, constituting a broad wedge dividing Germany and Austria-Hungary.

The three Austro-Hungarian armies deployed along a 320 kilometer (200-mile) front north and east from Lvov (then called Lemberg), Poland, and met the Southwestern Russian Army Group (comprising the Third, Fourth, Fifth, and Eighth Armies) southwest of the Pripet Marshes deep inside Russian Poland. They fought here in the Battle of Krasnik during August 23–24; it resulted in the retreat of the northern flank of the Russian Fourth Army.

Next, from August 26 through September 1, the Battle of Zamosc-Komarów forced the retreat of the Russian Fifth Army. In the meantime, at the southern flank of the engaged forces, the Austrian Third Army (together with some elements of the Second, which arrived from the Serbian front) suffered a setback at the Battle of Gnila Lipa (August 26–30). The combined Russian Third and Eighth armies drove this outnumbered force back to Lvov. A hasty Austro-Hungarian defense was quickly pierced by the Russian Fifth Army in the Battle of Rava Russka (September 3–11). The Austro-Hungarian forces fell back 160 kilometers (100 miles) to the Carpathian Mountains, leaving behind only a garrison in the fortress of Przemysl.

Austria-Hungary had provoked what became World War I for punishing Serbia. Now, the empire found itself menaced. Galicia (Austrian Poland) had fallen into Russian hands, and the Austro-Hungarian Army had lost 250,000 men killed and wounded, with perhaps another 100,000 taken prisoner by the Russians. Worse, Austria-Hungary had counted on two potential rivals, Italy and Romania, joining the cause of the Central Powers. Neither did this, however, and both would eventually join the Allies.

Most immediately threatening was the large Russian force that was assembled between Lublin and the Dniester River, poised to invade Galicia. In response to the vastly expanded war, the Austro-Hungarian high command shifted from its Plan B to Plan R, which required the transfer of an entire army from Serbia to Galicia. Dividing forces in this way consumed both time and resources, but the Austro-Hungarians pressed ahead. It was critically important to meet the Russian threat in Galicia, north of the Carpathian Mountains, where there was far more room to maneuver than in the mountains. Defeated in Serbia, Austria-Hungary was eager to win in Galicia and to prove itself an effective ally of the Germans.

The Battle of Rava-Ruska

Following defeat at the hands of the Russians in the Battle of Gnila Lipa at the end of August 1914, by September, the Austro-Hungarian forces found themselves being pushed back toward the Carpathians. To arrest this movement, Austrian field marshal Von Hötzendorf ordered his Fourth Army to break off contact with the Russian Fifth Army and attack the Russian Third, which was pounding the retreating Austrian Third Army.

The result, on September 5, was the Battle of Rava-Ruska, which resulted in yet another humiliating Austrian defeat. Although the Austrian Fourth Army saved itself, the Third Army was severely depleted, and Field Marshal Conrad ordered a general retreat. During September 12–26, Austro-Hungarian forces withdrew 160 kilometers (100 miles) to a position 80 kilometers (50 miles) east of Cracow, Poland. Galicia was now in Russian hands.

Germany Rescues its Ally

With Galicia lost (save for the besieged fortress of Przemysl) and Serbia victorious, the Austro-Hungarian armies were demoralized but still intact. Having achieved outstanding success against Russia, the German chief of staff, Erich von Falkenhayn (1861–1922), created a new army, the Ninth, to rescue the Austrians. They placed it under the direct command of Paul von Hindenburg, and just in time, for on September 22 the Russian supreme headquarters capitalized on its Galician successes by launching an offensive from the Polish Salient, around Warsaw and Lodz, into Silesia.

Hindenburg was quick to fathom the Russian intentions, and he knew that before they could launch the offensive, the Russian armies would have to be reinforced as well as realigned for maneuver and supply. The German commander struck first, before the Russians could organize their offensive. On September 28, he led the Ninth Army in a drive to take the Vistula River crossings from Warsaw to the San River. On September 30,

the Ninth Army, supported by the Austrians on the south, attacked west of the Vistula, battling through October 9. The Germans secured the Vistula south of Warsaw, but, outnumbered, Hindenburg’s Ninth Army was forced to retreat, not as a defeated force but as an engine of destruction. Hindenburg left behind a swath of wrecked roads and railroads as well as razed villages and farms. The Russians could not pursue.

The Battle of Lodz

Hindenburg and the Austro-Hungarian armies had withdrawn to their original lines by late October. But the retreat did not represent a Russian triumph. Fighting had cost the Russians heavily, and it had delayed the planned Russian offensive into Silesia. Hindenburg knew it was suicidal to attack the strong Russian concentration southwest of Warsaw, so instead, in cooperation with Ludendorff, he shifted his army northwest to the vicinity of Posen and Thorn, ensuring that the intervening villages and farms were destroyed.

The shift put the German Ninth Army in an ideal position to exploit a fatal flaw in the Russian deployment. The Russian First and Second armies were on the northern flank of the Russian Northwest Army Group. The German Ninth Army, now under the direct command of August von Mackensen (1849–1945), since Hindenburg had been elevated to overall command of the entire eastern front, advanced between the Russian First and Second Armies in the Battle of Lodz, fought from November 11 to December 6.

Rennenkampf’s First Army was almost destroyed, and the Second suffered a double envelopment. It was saved from annihilation by the Russian Fifth Army advancing from the south and a hastily assembled mixed Russian force from the north. That the Russians had halted the German offensive meant that Lodz was a tactical Russian victory, but because Russian losses were massive and the Silesian offensive had to be abandoned, the battle has been judged a strategic victory for Germany. German losses at the Battle of Lodz were 35,000 killed or wounded. Russian losses were estimated at 90,000 killed or wounded.

Germany Reinforces the East

Because Hindenburg and Ludendorff had produced substantial results in the East, whereas the western front remained a stalemate at the beginning of 1915, the German high command reluctantly allowed the transfer of some forces from the West to the East.

A new German force, the Southern Army, was created and placed under the command of General Alexander von Linsingen (1850–1935), intended to support the faltering Austro-Hungarians. Concerned that Russia would again advance into East Prussia, Hindenburg took it upon himself to create another new army, the Tenth, using four corps from the western front.

The Carpathian Action

Having failed to keep the Russians out of the Carpathians, the Austro-Hungarians, now supported by the German Southern Army, fought in the deep Carpathian snows during January–March 1915. The Russians sought to break through to the Hungarian plains, whereas the Austro-German aim was not only to prevent this, but also to relieve the fortress at Przemysl.

The Austro-German forces were up against one of Russia’s few truly able commanders, General Aleksei A. Brusilov (1853–1926); Przemysl ultimately surrendered to the Russians on March 18. With this loss, the Austro-German force withdrew to the Hungarian plains, setting up defenses that discouraged a Russian invasion. A weak Russian offensive ended in April.

The Battle of Bolimov

Simultaneously with the action in the Carpathians, Hindenburg and Ludendorff planned a bold move in the north: the double envelopment of the Russian Tenth Army. As bait, the German command team used the German Ninth Army, east of Warsaw, to draw the Russians to Bolimov, about 30 miles west of the Polish capital. Once the Russians were concentrated there, the German Eighth and 10th armies would launch an offensive near the Masurian Lakes.

At Bolimov, the Germans used a new weapon, xylyl bromide gas (code named “T-Stoff”), which proved remarkably ineffective, certainly giving no hint of the weapon that would soon terrorize the western front. The artillery barrage that accompanied the gas attack drew Russian troops away from the Masurian Lakes area, creating ideal conditions for the German offensive.

The Second Battle of the Masurian Lakes (the Winter Battle)

The Second Battle of the Masurian Lakes began on February 7. It would also come to be called “the Winter Battle,” because it began in a raging snowstorm. On the first day of battle, the Germans devastated the Russian Tenth Army’s left flank; on the second day, the German Tenth Army rolled up the Russian right flank. Completely surprised, the Russians retreated 80 kilometers (50 miles) southeast to the Augustow Forest. On February 21, the Russian XX Corps surrendered, having, however, sufficiently delayed the German offensive to permit three other Russian Tenth Army corps to escape.

The Russians avoided total defeat, but not devastation. Some 200,000 Russians were killed or wounded, and another 90,000 were taken prisoner. The German advance of 110 kilometers (70 miles) was halted on February 22 by the newly formed Russian Twelfth Army.

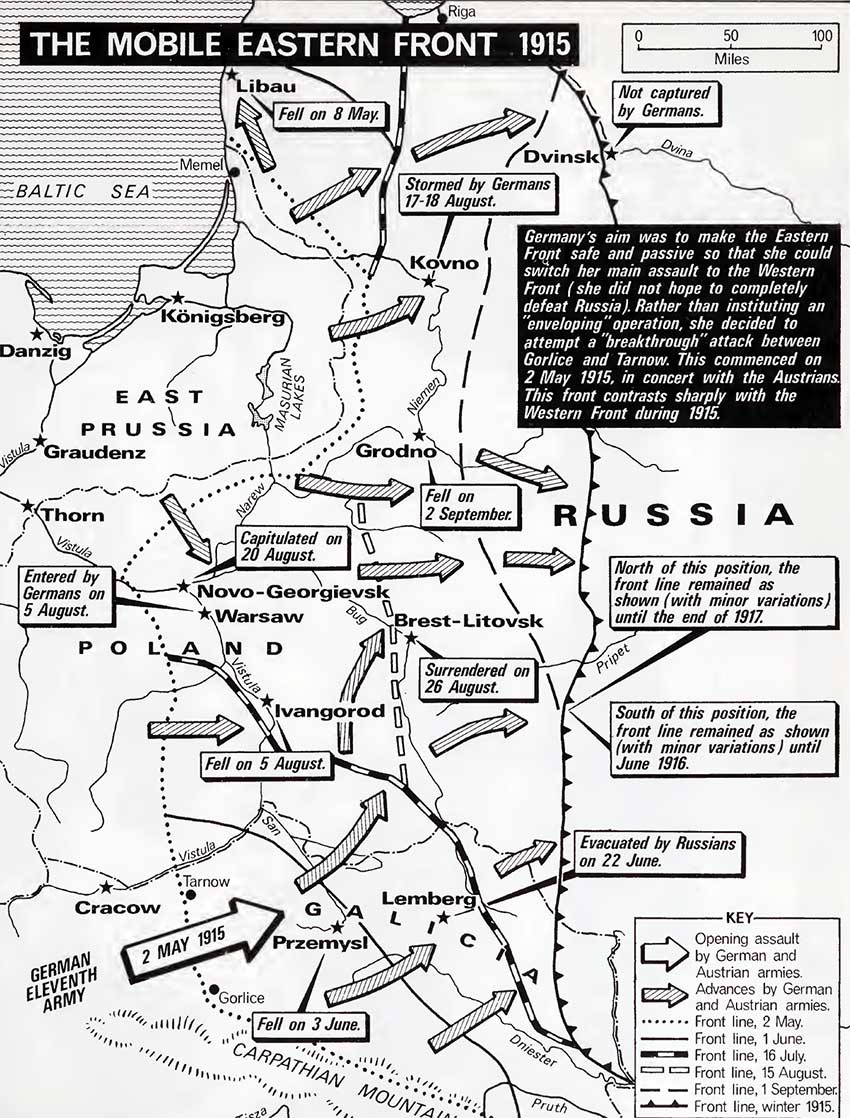

The Gorlice Breakthrough

Hindenburg and Ludendorff had not won, but they had dealt the Russians severe blows. After the Winter Battle, Hindenburg continued to engage the Russians north of Warsaw, while Mackensen’s German Eleventh Army, supported by Austrian units, attacked Russian positions between Tarnow and Gorlice, southeast of Cracow.

On May 2, 1915, the Austro-German forces broke through the Russian Third Army lines along a 45 kilometer (28-mile) front, making the first substantial crack in the Polish Salient. On June 3, the fortress at Przemysl was retaken; the town of Lvov was captured and occupied on June 22. During June 23–27, the Austro-German armies crossed the Dniester River, and the southern front now disintegrated. The German 12th Army advanced toward Warsaw, sweeping the Russians before it. Warsaw fell on August 7, heralding the total collapse of the Russian front and the end of the Polish Salient. By August 18, all the Russian armies had retreated to the Bug River, 160 kilometers (100 miles) east of Warsaw.

But the Austro-German forces continued to press their advantage. Brest Litovsk fell on August 25, followed by Grodno, to the north, on September 2. Vilna (in present-day Lithuania) fell to the Austro-Germans on September 19. By the end of 1915, the Russian front was 480 kilometers (300 miles) east of where it had been at the beginning of the year, and, in this crisis, Czar Nicholas II (1868–1918) assumed overall command of Russian forces. Of all Russia’s disastrous commanders, the well-meaning czar would prove the worst.

The Battle of Lake Naroch

From the perspective of Russia’s Western allies, the value of the struggle in the East was mainly to draw off German resources from the western front. It was France, desperately defending Verdun, that called on Russia to make an offensive drive in the Vilna-Naroch area of what today is Lithuania. The Battle of Lake Naroch (March 18, 1916) began with an intensive two-day artillery preparation, but the Russian infantry advance that followed soon bogged down in the mud of a spring thaw. The German defenders lost 20,000 men, but the Russians suffered at least 70,000 and perhaps 100,000 casualties.

The Brusilov Offensive

Undaunted by defeat at Lake Naroch, the Russians again responded to a call for an offensive, this time from the Italians. General Brusilov led the operation. On June 4, he attacked the Austro-German line in two places, with great skill and in absolute secrecy. The Austrian Fourth Army crumbled almost instantly, and the Seventh soon followed it. With the collapse of these two armies, 70,000 prisoners were taken. Unfortunately for the Russians, the high command failed to capitalize on Brusilov’s achievement, missing an opportunity to take Austria-Hungary out of the war with a single decisive blow.

As it was, German general Alexander von Linsingen led his army group in a counterattack against Brusilov on June 16 and checked the Russians’ northern advance. Brusilov renewed the offensive on July 28, achieving some success, but a shortage of ammunition and supplies frustrated him. By this time, German reinforcements had been transferred east from Verdun, and they bolstered the faltering Austro-Hungarians.

For all its success, they carried the Brusilov offensive out at a staggering cost to the Russians. By the end of June 1916, Russian casualties topped 1,000,000, a figure that helped propel the nation toward revolution.

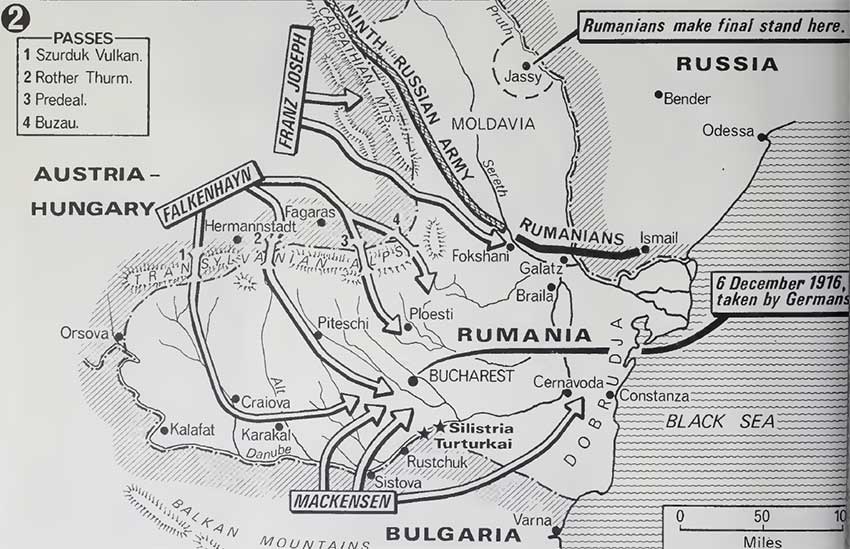

Romania enters the War

The Brusilov offensive propelled Romania, previously neutral, into the Allied camp on August 27, 1916. Romanian troops promptly invaded Austrian-controlled Transylvania, but they were repelled by the German Ninth Army. Simultaneously, the German-reinforced Bulgarian Danube Army crossed the Danube River on November 23, advancing into the Dobruja region and trapping the Romanians between itself and the Ninth Army.

Despite a skillful defense, the Bulgar-German forces soundly defeated the Romanian army at the Battle of the Arges River (December 1–4, 1916). Some 300,000 to 400,000 Romanians were killed or wounded (half of the deaths were from disease), and the survivors fled into Russia, leaving the rich grain and oil fields of their country in German hands.

The Russian Revolutions

The almost uniformly disastrous performance of the Russian army in World War I hastened the coming of the Russian revolutions of 1917. In March (February, according to the outmoded Julian calendar then used in Russia), the czarist government was overthrown and replaced by a Provisional Government, and in November (by the old Russian calendar, October), the Bolshevik Revolution installed the Soviet government of Vladimir I. Lenin (1870–1924).

Between March and October, the Provisional Government and the Soviets struggled for control of the nation. Aleksandr F. Kerensky (1881–1970) attempted to establish a coalition of the Provisional Government and the Soviets, but whether to continue fighting the war deeply divided the now starving nation.

The Second Brusilov Offensive

While Lenin’s Bolsheviks and Kerensky’s Social Revolutionaries and Mensheviks fought for control of the government, General Brusilov led the Russian 11th and Seventh armies against combined German, Austrian, and Turkish forces under German general Felix von Bothmer (1852–1937) at Lvov, near the Polish frontier.

Brusilov broke through the enemy lines for about 50 kilometers (30 miles) along a 160 kilometer (100-mile) front, and his subordinate commanders on either of his flanks made substantial inroads against the Austro-Hungarian Second and Third armies. But all of Brusilov’s brilliance as a commander could do nothing to stop Russia itself from dissolving beneath him. Morale and supplies both failed, and on July 19, 1917, German general Max Hoffmann led a counterattack that routed the starving Russian armies south of the Pripet Marshes in Galicia. The second Brusilov offensive ended.

The Riga Offensive

With the southern end of the Russian front destroyed, General Oskar von Hutier (1857–1934) led the German Eighth Army against the northern end of that front at the Baltic Sea port of Riga (in modern Latvia) and its fortress on September 1, 1917. Hutier employed rapid, violent tactics with special emphasis on the use of light, rapid infantry shock troops to penetrate the enemy lines at various weak points.

This secured the all-important ability to maneuver. Hutier’s technique was soon dubbed “Hutier tactics” and would be adopted by both the Central Powers and the Allies during the rest of the war. Under Hutier tactics, the Russian 12th Army fled the field in panic.

It was a panic that reflected the prevailing chaos of revolutionary Russia. Within weeks, Lenin’s Bolsheviks would be in charge of the government and would open up peace talks with Germany.

Russias Separate Peace

The Soviet government concluded an armistice with the Central Powers on December 15, 1917, and the following year signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. The Ukrainian Republic signed this treaty first, on February 9, 1918, although Soviet Russia held out for better terms. Germany was in no mood to negotiate and pressed its advance against undefended territory until, on March 3, Lenin signed.

The war on the eastern front ended, and tens of thousands of German troops were freed for service on the western front. Delivered either into direct German occupation or into the hands of newly created German puppet governments were Poland, Lithuania, the Baltic provinces, Finland, and the Ukraine. It was a total and ignominious defeat for Russia.

Principal Combatants (Eastern Front only)

Austria-Hungary, Germany, Romania, Bulgaria vs. Serbia and Russia

Principal Theaters (Eastern Front only)

Prussia and “Russian Poland,” the westernmost part of the Russian Empire, enclosed to the north by East Prussia, to the west by German Poland (Poznania) and Silesia, and to the south by Austrian Poland (Galicia)

Sources & further reading

- Michael Howard, First World War (New York, Oxford University Press, 2002)

- John Keegan, The First World War (New York, Knopf, 1999)

- George Kennan, Fateful Alliance: France, Russia and the Coming of the First World War (New York, Knopf, 1984)

- Dominic B. Lieven, Russia and the Origins of the First World War (New York, St. Martin’s, 1983)

- Geoffrey Jukes, First World War: The Eastern Front, 1914–1918 (London, Osprey, 2002)

- Dennis Showalter, Tannenberg: Clash of Empires (Lanham, Md., Shoe String, 1993)

- John Sweetman, Tannenberg 1914 (London, Cassell, 2002).

- {{#owner}}

- {{#url}} {{#avatarSrc}}

{{name}} {{/url}} {{^url}} {{#avatar}} {{& avatar}} {{/avatar}} {{name}} {{/url}} - {{/owner}} {{#created}}

- {{created}} {{/created}}