- Military History

- Biographies

- Militarians Biographies

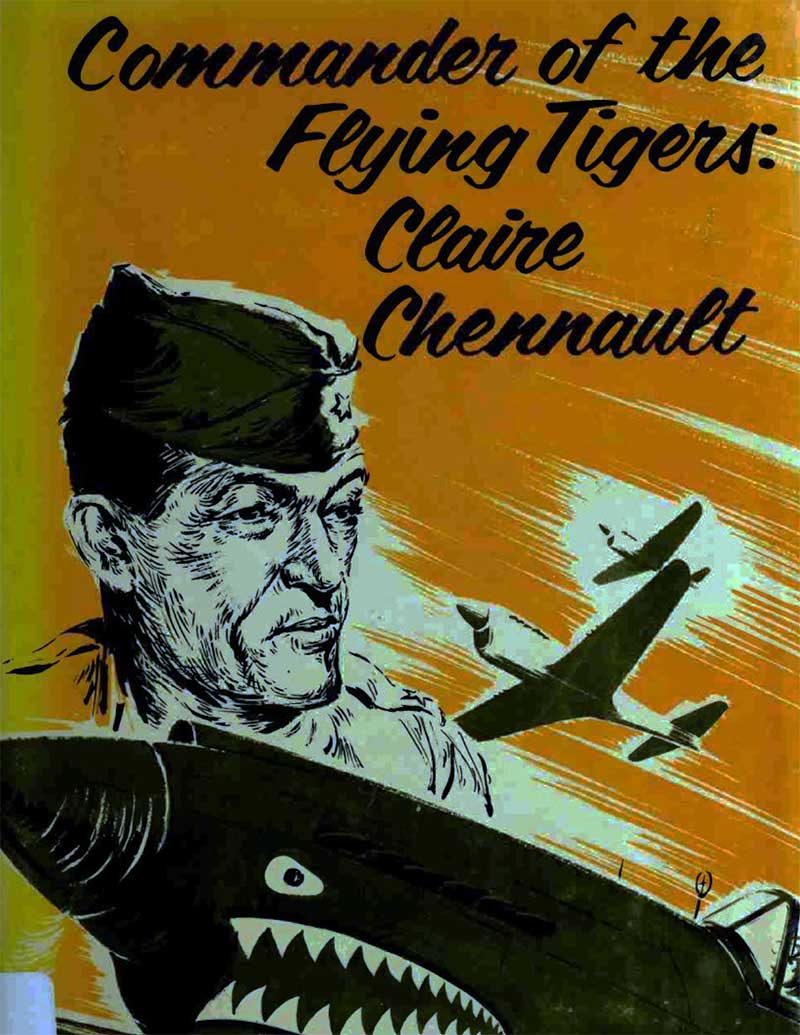

- Lieutenant General Claire Lee Chennault

Lieutenant General Claire Lee Chennault

The famous leader of the “Flying Tigers” - American Volunteer Group in China 1941

Claire Lee Chennault organized an ace group of volunteer American fighter pilots who risked their lives in China before the United States and Japan were at war. His Flying Tigers made military history even before the war officially started for the United States. They then struck one of the first blows against Japan after its attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941.

Claire Lee Chennault was born on September 6, 1890, in Commerce, Texas, the son of a cotton planter, and grew up in Louisiana. After preparing for a career in scientific agriculture at Louisiana State University, he gave it up to study to become a teacher. By the time World War I began, he was working as principal of a Texas high school. Chennault put teaching aside and joined the army in November 1917. He was commissioned a 1st lieutenant in the Infantry Reserve, but soon transferred to the aviation section of the Signal Reserve Corps, a communications unit of the army. They stationed him at various fields in the United States during the war and afterward joined the army's air service.

In 1923 he began a three-year assignment in Hawaii as commander of the 19th Pursuit Squadron and began studying aerial tactics. By night he calculated and plotted flight strategy, and by day he test-flew planes in the intricate patterns he planned on paper. Chennault spent the next few years as a flight instructor at various army airfields and was one of the outstanding authorities on pursuit aviation, a fearless pilot, and an able leader.

In 1932, he became the leader of a special army flying act known as “Three Men on a Flying Trapeze,” putting on probably the dizziest air show ever seen. He showed the maneuverability of airplanes under expert control. Chennault became partly deaf from flying in open planes, but rose to the rank of captain in 1929, and major in 1936. He retired from the army the following year and settled down with his wife and children in a cottage on Lake St. John near Waterproof, Louisiana.

His retirement didn't last long. Two of his flying circus comrades, J.H. Williamson and W.C. McDonald, had gone to China to organize an aviation school sponsored by Madame Chiang Kai-shek, wife of the Nationalist leader who opposed the expansion of communism in China. Chennault's friends urged him to join them, and when the Chinese offered him the position of air adviser, he went to China in July 1937 to take on the job of creating an air force to combat the Japanese, who would launch a full-scale invasion that year.

Chennault, then 47 years old, arrived in China to discover there were less than 100 first-line combat planes in the entire country and that Chinese pilots were insufficiently trained for combat. He realized that unless the Chinese pilots were better trained, their already insufficient number would diminish quickly. A few weeks after Chennault began his work in China, the Sino-Japanese War broke out. To solve the problem of how to bolster China's air power, Chennault formed the Chinese National Aviation Commission and set about making the Chinese Air Force into an effective fighting unit. He revised training procedures, taught new tactics, and established a vast radio and telephone network to signal the approach of Japanese bombers.

Chennault also put what he learned into practice by flying in combat with Chinese air forces over Shanghai, Nanking, and Chunking, fighting the Japanese. While he was training the Chinese to fight in the air, Chennault set up a series of air bases throughout the interior of China. He also helped organize an air raid system considered being one of the best in the world.

Chennault returned to the United States in 1940 to ask the government for planes to help the Chinese defend themselves. He was given about 100 small fighter planes, and several bombers, but when he returned to China and the planes arrived there, he found a shortage of replacement parts so severe that half the planes had to be kept in shop to keep the others in the air. There also weren't enough skilled mechanics or enough ammunition and, worst of all, not enough pilots.

Chennault returned to the United States in the summer of 1941 and asked Army Air Corps officials to give him some volunteers to both repair and fly the planes in China. Not wanting to get that politically involved in China's war with Japan, the U.S. government gave him permission only to recruit the personnel he needed. Chennault crisscrossed the country, going to air bases and talking to ex-army, navy, and Marine pilots and mechanics about the desperate need for them in China. The Chinese allowed him to offer pilots a salary of $600 to $750 a month p us a $500 bounty for every Japanese plane they shot down.

After a few months, Chennault had 112 volunteers, most of whom were eager to see action and didn't even ask about pay. He took the volunteers to Burma, just south and west of China, and set up a base camp 150 miles above Rangoon, the capital city of Burma, off the Bay of Bengal. Burma had separated from nearby British India a few years before and enjoyed a kind of independence, but was of great strategic importance to both China and Japan and soon would be invaded by the Japanese.

In Burma, Chennault created the American Volunteer Group(AVG) the way a coach would create a great football team. He also studied the P-40 fighters at his command and soon realized that most of his pilots were leery about the planes, which were obsolete and dangerous to fly. Chennault analyzed the capabilities of the enemy's Zero fighter and found the P-40 superior in several categories that could make it a better plane in aerial combat.

After drilling the pilots on aerial tactics, Chennault had them practice eight hours a day on each maneuver until it was perfect. By November 1941, he had ready two trained squadrons of 18 men each and a partial squadron of eight. Meanwhile, air bases, repair shops, and shelters had been built. The P-40s were plain olive-drab fighter planes with few distinguishing characteristics. Some pilots saw a picture in a magazine that showed a P-40 in North Africa painted with shark teeth. One evening they asked Chennault if they could paint leering sharks' mouths on the noses of their planes, to make the P-40s look distinctive and more ferocious. Chennault thought the idea would be good for morale, and that the sharks'-teeth images also might frighten the Japanese pilots, so he consented. Mechanics then painted a leering tiger shark grin, complete with a sinister eye on each plane.

As the pilots began flying the newly decorated planes, the Chinese called them "Flying Tiger Sharks," but to the rest of the world, they became known as Flying Tigers. As China’s war with Japan spread throughout the fall and winter of 1941, Chennault's volunteers were credited with being the spark-plug of Allied resistance all over the Asiatic mainland.

A few weeks after the attack on Hawaii on December 7, 1941, Japanese planes struck at the Kunming terminal of the Burma Road, a strategic supply road, but were surprised by the Flying Tigers. On Christmas Eve, Japanese bombers attacked Rangoon a thousand miles away, but Chennault's second squadron intercepted them before they reached the city. They destroyed nine Japanese planes. The following day, 70 enemy bombers attacked, trying to destroy the Rangoon docks, but the Flying Tigers brought many of them down. Outnumbered 20 to one, with only enough ammunition to fire one minute each time they took to the air, and with no reserves or support, Chennault's pilots kept up the attack for 90 days and destroyed 20 Japanese planes for every one of their own shot down. The Flying Tigers shot down 92 Japanese pilots for every one of their own lost.

Despite losses of planes and pilots and a shortage of repair parts and ammunition, the Flying Tigers held the skies over Burma for the Allies throughout February 1942. The rest of the world marveled at the heroics of a few American volunteers flying side-by-side with Britain’s Royal Air Force, winning victory after victory. Though the Flying Tigers had caught the imagination of the world, they were soon to be disbanded. They were a winning team, but they were an unorthodox fighting outfit, and U.S. military leaders decided Chennault and his pilots should join the army or go back home.

Chiang Kai-shek had made Chennault a brigadier general in the summer of 1941 and had awarded him the Chinese Military Medal. The following April, he was called to active duty in the U.S. Army and was given the temporary rank of colonel, with permission to continue his activities and relationship with the Chinese government. Five days later, they promoted him to brigadier general, and from July 4, 1942, he served with the U.S. Army.

Chennault made no secret that he regretted the end of the Flying Tigers, especially after only six of his pilots followed him into Army squadrons and most of the ground crews left. Assigned to General Joseph Stilwell’s command, Chennault put together an Army Air Force offensive capability that he said would expand until Japanese air power everywhere was smashed. His U.S. 14th Air Force pilots raided Japanese bases and planes at Hankow and Canton in South China and gained more fame.

Chennault did little flying himself after organizing the Flying Tigers, but worked from morning to night on plans and tactics and on mapping out attacks. While his pilots were in the skies, they reported him to be tense and high-strung. He would pace the floor of his office, leaving behind a swirl of smoke, tramping over a carpet of cigarette ends. He cursed interruptions, and no one could get more than a bark out of him until the last man was on the ground or accounted for. When one of his pilots did not return, Chennault was as hard hit as though the loss were his own son.

While on duty he was a stern disciplinarian, they said Chennault had a heart as big as all China, and his men knew it. Only five feet ten inches tall, his lean frame gave the impression of being taller. One of his pilots said he would sooner fight under Chennault than anyone in the world. Another called him one of the hottest acrobatic air pilots ever to kick around an Air Corps pursuit ship. Chennault headed the U.S. air task force in China until his retirement in August 1945 as a major general. He left shortly before they dropped the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the war in the Pacific ended. He retired out of exhaustion and also frustration because of disagreements with superior officers on how the war could be ended.

They awarded Chennault the Distinguished Service Medal for outstanding service as an intrepid and effective air commander of the 14th Air Force. Although limited by the difficulties of supply, to the smallest air force in the United States Army, he exacted a heavy toll of enemy personnel, shipping, material, and equipment. His force contributed beyond expectation to limiting Japanese air and ground activity and was a major factor in rendering impotent the enemy's air drive in China. In performing his task, General Chennault evidenced tactical and strategic skill, foresight and professional attainments which reflect great honor upon himself and the military service.

Chennault went home to Waterproof, Louisiana, and rejoined his wife and children. Restless in retirement, in October 1946 he returned to China, which was then engaged in a protracted civil war between the Nationalists and communists. He formed the Civil Air Transport (CAT), an airline that distributed relief supplies throughout China in aid of the Nationalists. Many of his pilots and ground crew had been members of the Flying Tigers and the 14th Air Force.

This work continued until late in 1949 when Chiang Kai-shek evacuated the Nationalist Chinese government from the mainland to Taiwan. In 1954, Chennault's CAT became involved in the war in Indochina, aiding the French against Vietnamese communists. The CAT carried tons of supplies to Korea, which helped America in the Korean War. It also flew out thousands of wounded and provided air transportation for U.S. Central Intelligence Agency operatives to establish training bases throughout the Far East.

Chennault returned to Louisiana and, after a long fight with lung cancer, died on July 27, 1958, at Walter Reed Army Hospital in Washington, D.C. at 67. Two days before, President Dwight D. Eisenhower phoned to say he had just promoted him to lieutenant general. Lake Charles Air Force Base in Louisiana was renamed Chennault Air Force Base and, in Taipei, Taiwan, a life-sized bust of Chennault was unveiled in the square near the Capitol building, the first statue of a foreigner ever erected by the Chinese on their own soil.

Lieutenant General Claire Lee Chennault - Quick Facts

- Republic of China

- United States

- 14th Air Force (United States)

- 1st American Volunteer Group

- Republic of China Air Force (Taiwan - since 1920)

- United States Army Air Corps

- United States Army Air Forces

- United States Army Air Service

- Brigadier General

- Colonel General

- Lieutenant General

- WWI (1914-1918)

- Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945)

- WWII (1939-1945)

- {{#owner}}

- {{#url}} {{#avatarSrc}}

{{name}} {{/url}} {{^url}} {{#avatar}} {{& avatar}} {{/avatar}} {{name}} {{/url}} - {{/owner}} {{#created}}

- {{created}} {{/created}}